I Envy Everyone Who Passes Away

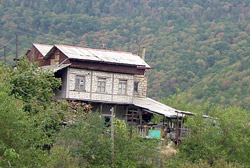

A narrow winding road leads to the village of Karin Tak (Under the Rock) in the Shushi gorge. The rock hangs over the village as if protecting it.

Karin Tak is the closest village to Shushi. Perhaps this is the reason that the state of absolute despair so characteristic of many Karabakh villages is not noticeable here at first sight.

The village is supplied with gas and telephone lines, has a kindergarten with 53 children attending, a school with 100 students, a club, three stores, and two libraries.

Old people and young gather at the club to play backgammon or chess, to watch television. The twenty-four-hour TV channel that shows romantic Indian movies with beautiful love stories is the favorite here.

From time to time, in the summer, a few tourists visit the village – mainly Diaspora-Armenians who are working in Shushi. Sometimes theater companies come here from Shushi with plays or concerts.

The impression of paradise on earth, however, disappears as soon as the villagers begin to tell the stories of their lives.

Every story in Karin Tak starts with the war. Even my little guides, the three sisters who walk around the village with me, first take me to the memorial to twenty-two heroes who were killed defending the village.

The villagers tell me that during the Karabakh war the village was under siege for two-and-a-half years until the liberation of Shushi. The Azerbaijanis called the village Dashalti.

The Azerbaijanis tried to seize Karin Tak three times. The decisive battle took place on January 26, 1992. Two Azerbaijani companies attacked the village. The villagers had about forty machine-guns, homemade grenades, and rifles. The battle lasted for several hours and twelve villagers and ten freedom fighters who came to help were killed. The Azerbaijanis lost 136 soldiers.

Karine's husband was wounded defending the village.

“My husband is a second degree invalid,” Karine says, “ but they awarded him the third degree to pay less. The pension for the second degree invalids is 30,000 drams (about $80) plus 4,000 drams for each child. But the pension for third degree invalids is 27,000 drams and no money for children.”

|

|

|

|

Karine's family lives with the family of her brother-in-law and the mother-in-law. She has three children and her brother-in-law has two children and thus, ten of them live in one small house.

“Is this a life?” Karine shrugs her shoulders. “We bought this house five years ago for $600” she points to the cabin next to their house. We slaughtered our pigs and sold them but now we have no money to make it habitable. We need to fix the roof, the floor, to paint the walls. And three years ago, on May 18 th , there was such a steady downpour that the house filled up with water. We spent whatever we had managed to save to repair it.”

The family has a vegetable garden and grows potatoes, beans, and cabbage. When they have produce, they sell it in the town. There is a daily bus to Shushi.

“My mother-in-law is wicked,” Karine whispers. When people here say “wicked”, they often mean grouchy.

“There are too many children; they fight with each other. We are impatient; we want to move. We went to different agencies asking for assistance but in vain,” Karine says.

When Karine speaks, there is no spite in her eyes but there is no sparkle of hope, either. No emotion appears on her face – only endless fatigue.

Karine's brother-in-law, Vladimir, who is the village medical attendant and the head of the aid station, has just returned from a patient. Vladimir remembers better times when the aid station was a branch of the central hospital of Shushi. The hospital used to supply the station with medicine free of charge and the villagers had opportunities to see doctors.

“Since 1999 we have been subordinate to the village administration. Now both the medicine and the salaries often come late,” Vladimir says.

His salary is 25,000 drams a month and the nurse is paid 20,000 drams. Both have not been paid for four months now.

Vladimir has a small plot of land in the neighboring village. There is no arable land in Karin Tak. “I was given a plot in Aghnakh,” he says, “but I can't go there every day. I hired a man; he cultivates the land and we split the profit.”

Vladimir is nostalgic for the Soviet era. “Back then, there was a branch of the Stepanakert electro-technical plant in Karin Tak with thirty villagers working there. We had a branch of the Stepanakert silk factory with seventy workers. We had a collective farm. But now…” Then he adds: “But despite the hard life no one wants to leave the village. Only one family has left the village since 1988. Even the young people, in contrast to other villages in Artsakh, aspire to get higher education in Stepanakert and return to the village. This year fifteen graduates of our school are studying in Stepanakert. Some young people work in various offices in Shushi, the others make their living by chopping and selling firewood.”

My guides have gotten bored in Vladimir's modest office. They prefer to introduce me to their friends and take me sightseeing.

Foreign tourists would go crazy about every panorama that opens from each village wall. Instead of using the road we are jumping from wall to wall.

“It's faster and more fun this way,” the sisters explain. The youngest sister, Anna holds my hand to prevent me from falling. She is just two or three years old. They are not afraid of anything, except cars.

“Have you seen the movie ‘The flower in the dust'?” ask the older sisters, Yana and Diana. It's their favorite Indian movie. They themselves are flowers in the dust and as beautiful. The girls love their village but they think it's boring here and there is nothing to do. They dream about moving one day to Stepanakert – “the big and beautiful city”—where Diana will be a model.

A grandmother with a militant look tells me that her name will tell me nothing. I ask my entourage to stop. The grandmother lost six close relatives during the war, including her son and daughter. She lives with the widow of her son and her grandson. Her other son is a second degree invalid and the other daughter is married and lives in Stepanakert.

“My son was awarded the order of the Military Cross of the Second Degree,” she says proudly. He was seriously wounded three times but he escaped death. But the fourth time the damned bullet killed him. He was thirty-one; there was nothing in the village—no medicine, no doctors. No one could come to help.” As for her daughter, she was taking food to the soldiers. She was just eighteen when she was killed. The woman remembers also her hero-dog who delivered “Prima” cigarettes to the soldiers when they were surrounded.

“My husband died last June. We borrowed some money to bury him, but this year we had no harvest and no beans to sell. I don't know how we are going to pay off our debt. We were given a plot of land but we have no farm hands. My oldest grandson is studying in Stepanakert, my daughter-in-law had two Caesarean sections—she can't do hard work. She works at the library and because of that she is not entitled to get a pension for her dead husband. I receive 16,000 drams a month for my son and 9,000 drams in my pension. Naturally, it's not enough. We barely make ends meet. I envy every one who passes away,” the old woman says.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment