A Fatal Life

Razmik Markosyan

“When I got off the bus, it was already night-time. It was freezing cold and snowing heavily. I immediately pulled up the collar of my coat and covered my ears by pulling down the ear-flaps of my hat fastening them with a knot under my chin. Then, with the help of a handkerchief, I tied the handle of my bag to my hand, so that I could have my hands warm in my pockets and headed towards the house of my acquaintance, which was at one end of the village and, fortunately for me, I was at that very end. I was walking in a massive headwind taking three steps forward and two back. Gradually my pace slowed down, which made me feel more and more anxious but I had no other choice – I had to move forward. The wind filled my eyes with tears, freezing instantly and wrapping them in ice. I was moving like a snake – frigid and unseeing. I could hear a wolf howling in the distance. I was there all by myself braving the elements and the howling of the predator. The stories about people dying or being frostbitten around that place were running through my mind. Although I was trying my hardest to overcome this difficult path, I added my name, in my mind, to the list of victims. Then, all of a sudden, I remembered that people living in those parts would tie ropes from their doors to their food stores located in their back yards to help orient themselves during snowstorms. Thus, I mentally held on to a rope from where I was standing to the house of my acquaintance and, with all the strength I could muster, I continued my way. I walked on and on with the imaginary rope in my mind. Despite the fact that the road was short, it took me nearly two hours to reach my destination. The road had taken all of me; I had a feeling I had walked for ages. At last I could see, right in front of me, the door that had always been open for me. That was it – I had done it! However, I was by then completely exhausted, and so unable to fully enjoy the sweet sense of triumph…”

This is an excerpt from my autobiography, a page in the life of the

It was a long time ago in 1978 when, having spent four years in jail #35 of the draconian regime, I was banished from

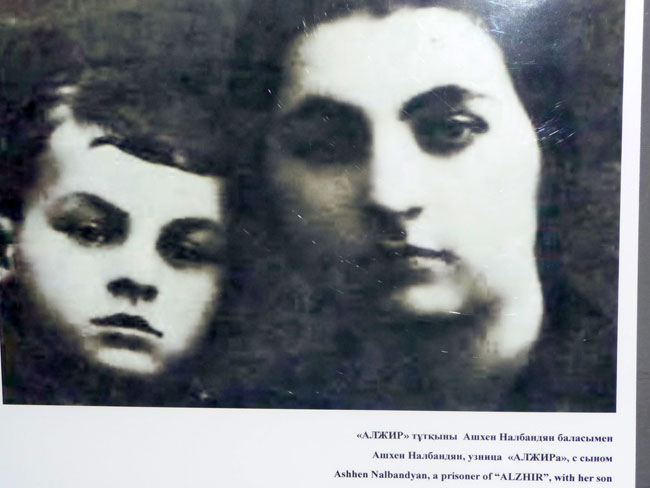

Ashkhen Nalbandian is Vahan Terian’s relative, and the mother of Bulat Okudzhava, a famous poet and song-writer.

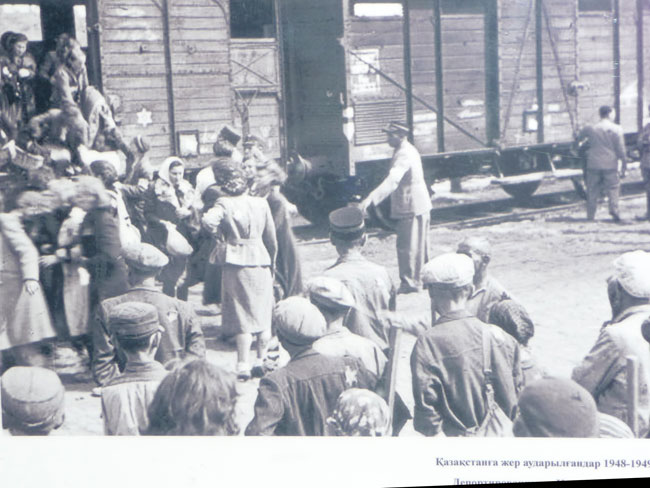

The wives, too, were labelled as “homeland traitors and enemies of the people” because they did not think of their husbands as such. 20,000 women “dwelt” in this world of anguish and torment and their children were imprisoned in the same neighbourhood. The job of accommodating 25,342 young exiles in the camp was undertaken by Nikolai Yezhov, the Head of the NKVD (The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs). There was no possibility of two acquainted or related children to be lodged at the same orphan-camp. The arduous task of bringing up young teenagers was entrusted to criminals who carried out their mission with a so-called “strong sense of responsibility.” Only newborn babies had a right to be with their mothers. From 1938 to 1953, 1,507 fatherless children were born to imprisoned women who had to endure innumerable rapes at the hands of their jailers.

Years later, there still were numerous places of exile for political prisoners. Those who had made major inroads into the state system became political prisoners because they dared to speak out about the independence of the Soviet republics. The Main Directorate for State Security had two main motives behind this deed. Anyone aspiring to become independent from the

The army of ideological fighters against the

|

|

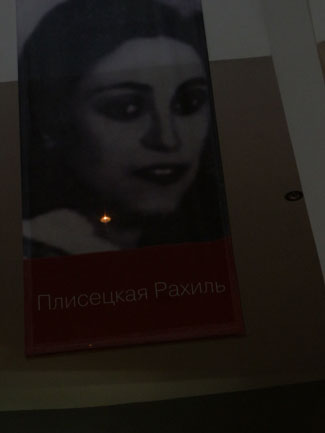

| Lidia Rouslan ova | Rakhil Plisetskaya |

Thirty-two years later, acting in my capacity as Head of the Armenian delegation, I arrived in the

It had been years since I was that close to Kenbidaik. The desire for my past life, seeming at times purely illusory, did not allow me to stay in

Strangely enough, I had missed Kenbidaik and felt frightened that the village could have disappeared entirely along with the other places of the

On my way to Kenbidaik I was experiencing an inexplicable sense of great achievement. I was going to the place of my banishment, to the village where I had once lived as a political criminal. Something that had been unrealizable and even horrifying to so many was now reality. For the local people, at the very beginning in particular, I and my hunger for freedom had been strange and incomprehensible anomalies. I was an “anti-Soviet” person, someone who daringly opposed to the absolute; no matter how utterly inhuman and cruel it was, it was, nonetheless, the most palpable and tangible power for an ordinary village dweller knuckling under the flow of life. Beyond this super-power was total uncertainty and in their eyes I was the ambassador of uncertainty and instigator staging a super-power revolt. Now that the dream, for the sake of which I had been an obscure exile in “my village,” came true, I could not wait to look into the eyes of that foreign habitation which was surprisingly dear to me in my memories.

The road passed along the Soviet “ALZHIR” labour camp, which was situated 100 km away from the

Today “ALZHIR” is the museum of the GULAG forced labour camp and a significant portion of the truth has already been restored.

But what is concealed in Kenbidaik?

The car slowed down as a big road-sign appeared welcoming us to Kenbidaik. Outwardly, I remained perfectly composed. My emotions were so personal that I thought proper to conceal them.

Kenbidaik lay in front of my eyes almost entirely deserted. Once a viable international settlement, it now was a sparsely populated village. No more political exiles, no more repressed prisoners whom the Soviet (state and) political cobweb insidiously crammed into its infinite spaciousness, reminding of one enormous labour camp, to artificially revive the desolate areas. The local villagers were gradually outnumbered by exiles, prisoners and “special re-settlers.” I do not know whether it was a perfectly normal life they were living or, rather, a precarious existence, or even death.

To be able to orientate myself in my old “forced” settlement, I tried to find the village club and cafeteria which had, in the years of my exile, born witness to the liveliness of rural areas. However, unable to detect any trace of them, I began to roam the places unfamiliar to me. I walked and walked continually as though I was looking for something but I did not know what it was I was looking for. Soon, to get rid of this pointless search, we moved on to the neighbouring village. I was guided by my recollection of one dreadful winter night and, before long, I came in sight of another place in a state of dilapidation. It was impossible to stay out there without a protective net due to impudent swarms of mosquitoes. Mosquitoes had always been there but not in such large quantities as now because the necessary measures had been applied consistently by the former system.

I quickened my steps toward the familiar house at the end of the village. There it was again, miraculously, looking thirty years older! I approached it and knocked on the door. The door of this house where an Armenian family lived had always been open for me. It had been a God’s gift to me during the years of my exile. I looked at their faces. They were young and unfamiliar. A short while later an elderly woman entered the room. Her face seemed very dear to me. I introduced myself and told them my story. The woman, recognizing me promptly, sent someone to call her husband who had left home for some business. Shortly afterwards, I and an old acquaintance of mine, aged and half-alive like his village, were standing there face to face.

He, too, recognized me immediately. People usually reminisce about the past with pleasure but the man talked about the past discreetly, perhaps sparing me from the recollection of my past exile life. The present was silenced altogether but it was not a sad silence. One cannot be sad about all the times they have lived; I think we should be able to mentally cling to the life rope in difficult times. I was looking at the members of his family thinking about what the future held for them and later I came to realize that their future would be exactly the same as the following day of the village they lived in. I did not know what it would be like but I did know that life would decide their destiny, not death.

Seeing me off, my old friend said to me: “You have won!” I smiled at him.

The Soviet tyrannical power had failed to “correct” me – I did not want to see Kenbidaik thriving and inhabited by former exiles. Instead, I longed to see it as if there had never been the Soviet power in the history of this village. A barren landscape was all around and the moment of our farewell was sad. I, however, smiled at my friend and replied: “I know.”

I knew I had won but the price that I had paid did not allow me to fully enjoy my triumph. Therefore, I decided to leave it all to my old friend’s offspring.

P.S. Several days ago, with the help of Vasili Ghazarian, the Ambassador of Armenia to the Republic of Kazakhstan, I discovered that among the “ALZHIR” prisoners there were 80 Armenian women condemned as “homeland traitors and enemies of the people.” The Armenian side is currently conducting negotiations to obtain permission to install a plaque in the Akmolinsk camp area. I have managed to acquire a list of Armenian victims to be publicized for the first time. Should you have information about any of the female prisoners in the list below, please refer to the editorial board of “Hetq.”

Of all the women included in the list, we have information about Maria Lisitsian, who founded a

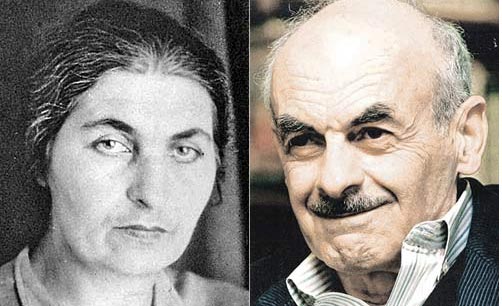

Ashkhen Nalbandian Bulat Okudzhava

In Ashkhen Nalbandian’s dossier there remain only two of her letters of appeal. In one of them she asks the Bolshoy Uluy authorities to move her to Dudinka: “I have not been able to find a job in Bolshoy Uluy. There are no prospects for me here. I have a higher education and have worked as an economist and financier. I kindly ask for permission to be moved to Dudinka where I shall be able to work and get paid.” Her request was not rejected. She, however, was unable to move due to lack of money for her move. Ashkhen’s second request related to a reconsideration of her case. “I am not guilty,” – Ashkhen wrote. The reply was as follows: “Request rejected. You have been deservedly condemned.”

List of Armenian prisoners in “ALZHIR”

(original spelling is preserved)

- Sofia Christopher Avetissian

- Tamara Ivan Avsharova

- Anahit Artem Aghababova

- Rizhik Baklyarov Aghajanova-Mughdussi

- Gayaneh Sergei Adamian-Hovanessian

- Nina Lvov Ayvazova

- Maria Vardan Alibekova

- Yevgeniya Soghomon Aroustmova

- Ashkhen Grigor Aslanian-Vardanian

- Sofia Mikhali Atarbekova

- Reqsima Melkoumov Hakhoumian

- Nina Jakov/Hakob Balayan

- Asyu Arsen Barkaya-Toutouijak

- Arkiozan Constantine Barseghian

- Maria Semyon Bekzadian

- Anna Avetovna Boublichenko

- Varvara Arkadi Varnazova

- Satenik Ivan Velikanova

- Sofia Arkadi Vizirian

- Satenik Semyon Gharibova

- Tamara Fade(h) Georgieva

- Roza Lvov Gloushanova

- Susanna Manouk Goroshchenko-Avetissian

- Haykanoush Avet Grigorian-Manvelian

- Maria Avet Davidova-Kirakozova

- Maria Nerses Davtian

- Paytsour Aghabek Yenoukova-Grigorian

- Titanic Gaspar Yeremian

- Tamara Sergei Zyulgoudarova

- Haykanoush Lazar Ivanian

- Nadezhda Stepan Illina

- Nadezhda Stepan Ipolitova

- Yelena Adam Kamarauli Karakhanova

- Susana Aghajan Kasparova

- Sofia Mikhali Katsova

- Sofia Mikhail Kouroverova

- Maria Artem Koushvid

- Polinea Maikhailov Levinskaya-Plotkina

- Susanna Andrei Legat

- Anna Sergei/Sargis Lezhava

- Araqsi Thomas Malevich

- Margarita Artemovna Malkhossian-Batkissian

- Gaayu Arest Mamikopova

- Taqou Moukouch Manoukian

- Yelena Ivanovna Melikova-Piralova

- Armena/Armendi Sargis Minassian

- Varsenik Minaevna Mirzabekian

- Anna Martich Mnatsakanova

- Parandzem Balajan Moussaelian

- Haykanoush Alexander Najarov

- Ashkhen Mikhail Nekrasova-Nazarian

- Maria Avet Nersessian

- Yelizaveta Bassil Pavlovskaya

- Anna Martiros Paliokha

- Anahit Georgi Parzian

- Araqsi Mikhayil Paronian

- Aroussa Karp Pertchian-Grigorian

- Tamara Iosif Petrossian

- Maria Tigran Poghossian

- Maria Yerem Pournis/Sanahian

- Astad Karl Ratikhan Azlara

- Anahit Ivan Stepanian-Bagatourova

- Rshtouni Gevorg/Georgi Souqiassian

- Varvara Grigori Soulkhanova

- Yevgenia Arsen Taginosava

- Maria Stepan Taktakishvili- Naskidova

- Yelena Vassil Taroumova-Ayroumova

- Sofia Sergei Ter-Davtian

- Marianna Karp Thomson

- Amelia Semyon Pilipossian

- Yekaterina Alexander Khitarova

- Ashkhen Grigori Tsatourova

- Yevgenia Grigori Tchavtchavadze

- Maryu Hambardzoum Cholakhian

- Yekaterina Zaqar Chkhikvishvili

- Asya Bogdan Shafirova

- Margarita Hounan Youzbashian

- Barika/Goharik Hovanes Yakhontova

- Maria Vardan Lisitsian

- Ashkhen Stepan Nalbandian

Translated by Marine Yandyan

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (9)

Write a comment