Gyumri Painter: “People don’t have money so they buy those Chinese imports”

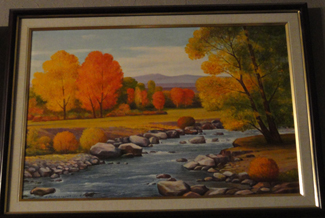

Natural landscapes and Armenian churches dominate the oil paintings hanging from the walls of the Gyumri living room of 82 year-old Aleksandr (Shoura) Zhamakochyan.

The room reminds a visitor of a small art gallery.

Mr. Zhamakochyan confesses that like many others the 1988 Spitak earthquake has divided his life into pre and post-earthquake concepts and that the disaster has also influenced his artistic works.

The atheist communist saw the light and became a devout Christian while cowering under the panels of a building that collapsed around him. He was baptized at the age of 56 and made it his life’s mission to eternalize all Armenian churches by painting them.

Even though Mr. Zhamakochyan gets around with the aid of a cane, one glimpses a nimbleness of step in the artist. He sits in an armchair and suggests that I take a seat on the couch. Tamara, his daughter, rushes to the kitchen to make some coffee.

He speaks clearly and his memory remains unclouded by time. Nevertheless, the artist senses my unease and responds with a laugh. “On occasion my hearing fails me and my feet hurt. Other than that, I have no deficiencies,” Mr. Zhamakochyan says, explaining that his humor has been inherited.

Mr. Zhamakochyan’s grandfather was known in Gyumri circles by the moniker “Tapak Seto” - a man who liked to joke and entertain friends at a snack bar he ran near the Gyumri bus station. People visited not just to eat but to hear Seto’s unique sense of dry wit.

Aleksandr says he inherited his humor and artistic tastes from his grandfather.

“I would have surely become an ambassador if allowed. But my father was a man of position and he wanted me to become a doctor. Of course, it wasn’t for me. My world was painting. My brother became the doctor. I lasted two months at a medical school before leaving. I then enrolled as a corresponding student at the Novosibirsk Kuybyshev Engineering and Construction Institute. I figured it would be alright to become a draftsman and that at least it was akin to painting,” the artist tells me.

Mr. Zhamakochyan has inherited his talent for painting from his mother, a member of the Narimanashvili family, who were famous artists in Georgia.

“My mother was a Georgian who married my father when she was seventeen. She could prepare delicious meals, both Armenian and Georgian. My only child, Tamara, is a pianist. Her three kids are all good painters but they pursued medicine and became dentists,” says Mr. Zhamakochyan.

Shoura started painting as a young child and his talent was discovered by a friend who was enrolled at Gyumri’s Merkurovi Art School. The friend, upon seeing some of Shoura’s paintings, suggested that he visit the school as well. The principal placed a piece of paper and a pencil in the young boy’s hand and told him to sketch. He was admitted to the school on the spot.

In 1963, while taking classes at the Novosibirsk institute, Mr. Zhamakochyan also worked at the Leninakan (former name of Gyumri) “Hay Reklam” advertising company as a drawer.

“My boss was Khachik Vardbaronyan. We worked together for thirty years. And what years they were. I met some fabulous artists. We all know that painters like to have a good time, so we’d get together often. We’d frequently go to Moscow. Back then, you could buy a ticket in the morning, fly out, and return that same night,” the painter says with a grin, leaning his white-haired head to one side. “You don’t believe me? It’s the truth. Travelling to Moscow was easy. Now it’s expensive and time consuming.”

He recounts those parties where artists like Minas Avetisyan and Hakob Hakobyan would show up. Mr. Zhamakochyan even had an opportunity to work with John Papikyan, an artist awarded the title Meritorious Painter of the USSR, who was teaching at Leningrad’s Ilya Repin Academy of Arts at the time.

Mr. Zhamakochyan tells me life was good back in the day. He made 700-900 rubles a month at the advertising company and painted when he had the time. The artist recounts that on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Lenin’s birth he won a 1,200 prize and spent it all on a piano for his daughter.

Today, Mr. Zhamakochyan receives a 48,000 AMD (US$102) monthly pension. He also sells some of his paintings for additional revenue.

|

|

“I have no paintings left for sale. Whatever is left can be used for an exhibit. I sell copies of the original. I used to take them to a salon on Rizhkov promenade in Gyumri. The life of a painter has gotten much more difficult today. People now prefer to buy those Chinese imports that are less expensive. I’m not saying that the numbers who appreciate real art have decreased, it’s just that people don’t have money. So they buy those Chinese imports and hang them on their walls.”

Mr. Zhamakochyan hasn’t been able to stand before his easel for a few months now. His legs hurt and his walks around his beloved town of Gyumri have become rarer. Currently, he’s trying to finish older sketches. He’s painted for his grandkids and now paints for his great grandkids.

|

| Tamara and her father Aleksandr Zhamakochyan |

In his heyday, Mr. Zhamakochyan participated in numerous group exhibitions. The artist laments that he hasn’t painted his beloved Gyumri all that much.

“I’ve never had the desire to live anywhere else. I’ve only stayed in Yerevan for a few hours at most. This town is in my being,” he exclaims, complaining about a recent bout of memory loss. “It’s mostly names that I can’t immediately recount. They come to me later.”

Tamara says that her father loves football and is a big Chelsea fan. “When he forgets the Chelsea name, he immediately phones my husband. ‘Ashot, those gunsmiths are playing.’” Tamara says with a grin.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (1)

Write a comment