Refugees Are a Separate Nation

Last December I met with Azerbaijani colleagues at a seminar inTbilisi.

During the coffee breaks we spoke on subjects of common concern for Armenians and Azerbaijanis. I told them that I had read in the Azerbaijani press that the refugee problem had been solved inAzerbaijan. “Yes, houses were built for them,” a colleague said. “ But if you want to know, the refugee problem is something that will never be solved. You build houses, jobs are needed; you provide jobs, social status is needed, and so on.”

I remembered a woman I had met in thevillageofJaghatsadzorin Gegharkunik Marz who had no particular problems with housing or acute social needs, but stood out because she hadn't accepted Armenian citizenship.

Compared to Nina Kadamyan, who unexpectedly found herself on a ferryboat taking her to Krasnovodsk, Turkmenistan, or Svetlana Arustamova, who escaped to Yerevan from Baku leaving all her belongings behind, or Sona Chichyan, who was evacuated from Getashen by a helicopter in a matter of minutes, or Samvel Movsisyan, who walked through forests day and night first from Shahumyan to Stepanakert then to Yerevan, the sudden turn in their lives happened smoothly for Jemara Vardanyan and her family.

Azerbaijani neighbors had helped the Vardanyan family, hiding them from the gangs that were expelling Armenians.

“They found out our whereabouts and were stoning our house. Our Azerbaijani neighbor wrote on a piece of paper that there were no Armenians in our yard and attached it to the gate. We were there but he wrote that and stuck it to the gate,” Jemara Vardanyan recalled.

“They found out our whereabouts and were stoning our house. Our Azerbaijani neighbor wrote on a piece of paper that there were no Armenians in our yard and attached it to the gate. We were there but he wrote that and stuck it to the gate,” Jemara Vardanyan recalled.

Then they had managed to come toArmeniaand bring their belongings with them. Later Jemara's mother-in-law went to Khanlar, found the Azerbaijani owner of their present house and exchanged houses. “She went to Khanlar, met the Azerbaijani, exchanged the houses, took all the documents, and came back. We moved to this village on March 2, 1989, unfortunately.”

Jemara said that “unfortunately” mainly concerned their social status, though the problems of daily life were not minor, either. They brought water from a well located 200 or 300 meters away. With snowfalls, the village became isolated from the outside world. “We go to the regional center to buy sugar, cigarettes, matches. We leave at 10 in the morning, several people get together and we go,” Jemara said, adding that besides these difficulties, the presence of wolves was a big problem. “No one takes care of it, but people are not allowed to keep rifles.”

The village has no first-aid clinic. People who live in Jaghatsadzor must go to the neighboringvillageofShatvanfor medical services. Thus first aid is inaccessible during the winter because of the snow and the wolves, and in summer, just because of the wolves. Jemara told me that the doctor from Shatvan once narrowly escaped falling prey to wolves.

Doctor Zoya Hovhannisyan confirmed this. “Yes, it's true. I was walking to their village and wolves appeared in front of me. I don't remember how I ran away and darted into the house; I just remember that for a few days my temperature didn't fall below 40 degrees - probably because I had been frightened.”

Doctor Zoya Hovhannisyan confirmed this. “Yes, it's true. I was walking to their village and wolves appeared in front of me. I don't remember how I ran away and darted into the house; I just remember that for a few days my temperature didn't fall below 40 degrees - probably because I had been frightened.”

After that incident the doctor never went to the village on foot and asked them either to send a car or to come to her. “For example, there was one childbirth in January, so they called a taxi and managed to bring the woman in labor. Often they come here on foot. It happens that some four or five men from the village get together and come here to take me with them. They either take me there or bring the patient here, depending on the illness.”

All of this added up was the reason that Jemara Vardanyan's family refused to accept Armenian citizenship. And despite not having citizenship, when their Khanlar-born son turned 18 the family decided to go to the military registration and enlistment office to have him drafted. “My husband thought, ‘He's a boy why. Why should he miss his military service? Let him go to the Army,” Jemara Vardanyan said.

Not having citizenship was a sort of revolt against falsehood. “Who is concerned about you, whether you are a citizen or not? No one. No one cares for us,” Jemara said, and added that discrimination existed between locals and refugees. She said refugees were second-class, voiceless people, though they have lived here for 17 years now.

“If I were to go out and speak up they would say, ‘Here are they – the gyal ma' . They call us gyal ma here. Gyal ma is a Turkish word meaning ‘Don't come.' I don't know why they use this word. I fought a lot against this word but I can't bring it home to them that this is unacceptable world.”

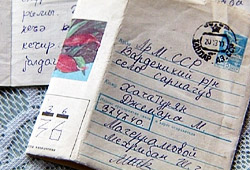

Jemara recalled that in 1989 just after she moved to Jaghatsadzor, she got a letter from Khanlar. “Our Azerbaijani neighbor wrote that everything was quiet and settled and that we should come back home and no one would hurt us. And that they couldn't get along with the newcomers there.”

Jemara recalled that in 1989 just after she moved to Jaghatsadzor, she got a letter from Khanlar. “Our Azerbaijani neighbor wrote that everything was quiet and settled and that we should come back home and no one would hurt us. And that they couldn't get along with the newcomers there.”

It's not difficult to understand the social status my Azerbaijani colleague was talking about, and it's not difficult to understand that refugees are a separate nation – rejected by all nations.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment