Resurrection: Building of Soviet Yerevan

By Vrej Haroutounian

Here, Green and round, Armenia extends to three seas. Here, to two. Here, to one, and here-not even to one. So swiftly does Armenia diminish from the first map to the last, always remaining a generally round state, that if you riffle quickly through the atlas, it’s a movie: it captures the fall of a huge round stone from the altitude of millennia. The stone disappears into the deep, diminishing to a point. But if you riffle the pages from the end of the beginning, it’s as if a small pebble has fallen into the water; and historical circles are spreading across the water, ever wider and wider.

Andrew Bitov, A Captive of the Caucuses

Yerevan, as the capital of Armenia, is always at the center of national pride, there are cultural festivals commemorating Yerevan-Erebuni anniversary and the ancient origins of the city on an annual basis. While such commemorations are important, many Armenians are thus misinformed as to the fact that contemporary Yerevan was built not too long ago.

This is significant because at times, in recalling the grandiose success of ancient ancestors, people seem to forget about the city’s contemporary origin and current life; somehow forgetting that how current generations manipulate that same city is what will be left for future generations.

A narrative focusing on the ancient casts a shadow over the contemporary, over the now, over the still being built. By celebrating the ancient past, significance is placed on the accomplished and helps to avoid the dialogue as to what is being built now. Understanding the contemporary history of Yerevan and the effects of economics, politics, and cultural shifts explains how it transforms from Lenin’s idealist era to the end of the union with Gorbachev’s economic reforms, and what takes place after independence. The goal of these series of articles is to dispel the shadows of grandiose memories and to bring back the focus to the now, where changes are taking place.

“Between 1914 and 1921, the Armenian people suffered what is recognized as one of the first modern genocides. Between 1 and 1.5 million Armenians were killed, while countless others were systematically deported. The Armenian people, having almost entirely been driven out of their historical territories, had either been forced into foreign countries, or had migrated to Yerevan, which became the capital of present-day Armenia in 1918. The Genocide eliminated Armenians from nearly nine-tenths of their historic territories in Turkey, where the Armenians claimed a small fragment of land in the Russian Transcaucasia region as their ancestral home. The Genocide also created a new or expanded diaspora community throughout the Middle East, Europe, and North America. For the displaced, the Genocide served as a significant part of their identity that would define future generations.” (Dudwick, 1997)

Contemporary Yerevan was built after the end of World War One - when refugees hungry and tattered came together to resurrect a new home for the Armenian people. What followed was a giant urbanization effort that still continues today.

“The first Armenian republic, formed by displaced refugees, encountered food shortages and disease. The refugees who migrated to Yerevan arrived to a city that was not ready to incorporate an influx of 700,000 incoming people. Most of the roads at the time were still unpaved; most housing was single storey with very few two and three-storey buildings. The United States provided some aid, but it was not enough to prevent famine. Weak and with no allies in the region, the newly-formed independent Armenia had to push back all its neighboring countries’ advances to establish its borders on what was left of its historic Armenian territories.”(Suny, 1993)

Substantial aid from the West never arrived, forcing the government to turn the new Armenian state over to the Communist Party on December 2, 1920. “By 1920 only 720,000 lived in Eastern Armenia, a decline of thirty percent. In the seven years of war, genocide, revolution, and civil war…Armenian society had in many ways been demodernized, thrown back to its pre-capitalist agrarian economy and more traditional peasant based society.” (Suny, 1993, in Karanian,1994, p.65)

“In 1920, Armenia became incorporated as part of the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union provided security from external threats, but this came at the cost of national identity and further loss of Armenian populated lands to the Soviet Republic of Azerbaijan.” (Suny, 1993)

“By 1930, the peasantry had been organized by the Communists, and, by 1975, Armenia was an urban, industrialized society with two-thirds of the population living in cities and towns, and only 20 percent of the population working in agriculture and forestry. The remaining population worked in industry and service.” (Dudwick, 1997)

“The creation of a Soviet republic in Armenia came about not through a popular uprising or the enthusiastic demand of the people but rather as a measure of last resort...It was to be a revolution imported from outside and directed from above.” (Suny, 1993, p.138)

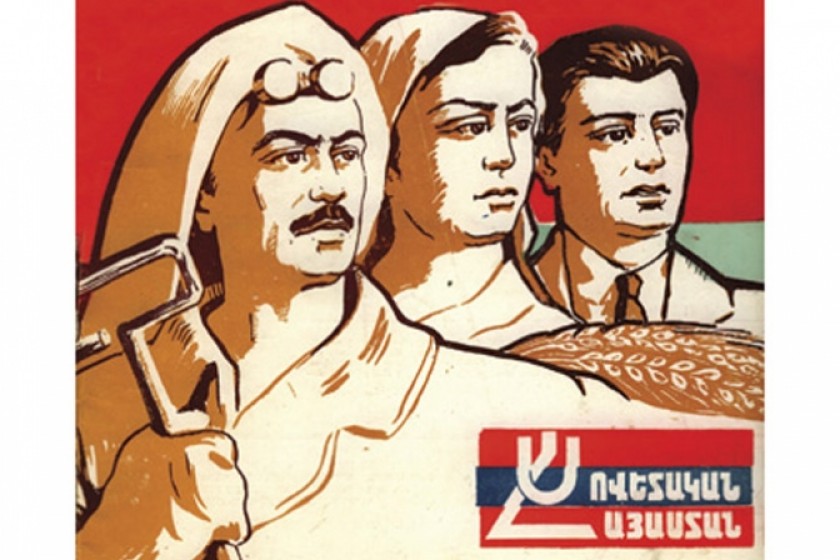

The Soviet Union allowed opportunities for Armenians to preserve their national identity within the socialist system. Armenian Communist Party members were not asked to cease being Armenian, but were simply asked to become a Soviet Armenian.

“For Armenians living in their titular republic, the defense of their ‘nation’ – whether of the Armenian language, church, cultural heritage, or history— functioned simultaneously as an attempt to heal the physical and psychological trauma of the Genocide and to protect local interests and traditions.” (Dudwick, 1997, p.45)

Soviet Armenia experienced five phases of Soviet policy referred to as the Lenin Era, Stalin Era, Khrushchev Era, Brezhnev Era, and Gorbachev Era.

These political phases each left their own mark on the urban landscape of Yerevan, as political, economic and cultural developments emerged. In order to understand the changes arising during the Soviet Era, the different political, economic, and cultural forces in place during each of the five phases are characterized and explained below along with their corresponding imprint on the urban landscape.

“The first phase of modern-day Yerevan started with the era of Vladimir Lenin. After the revolution of 1917, the Soviet Union was politically a militant, socialist dictatorship led by the Bolshevik Communist Party.” (Suny, 1993)

“The economic policy of the time was “State Capitalism,” a strategic policy in which farmers were allowed to keep excess shares of their grain supply.” (Suny, 1993)

“The economic policy of the time was “State Capitalism,” a strategic policy in which farmers were allowed to keep excess shares of their grain supply.” (Suny, 1993)

“At first, the members of the Armenian Communist Party believed in the creation of a new society, and ambitious youth were eager to become Soviet Armenians.” (Dudwick,1997) “ Armenian was the language of use in this time period, though the number of school children enrolled in Russian schools was growing. Parents increasingly wanted to send their children to Russian language schools, seen as providing further upward mobility.” (Dudwick, 1997) Yerevan State University was established in 1920.

Effect of the Lenin Era on the Urban Landscape

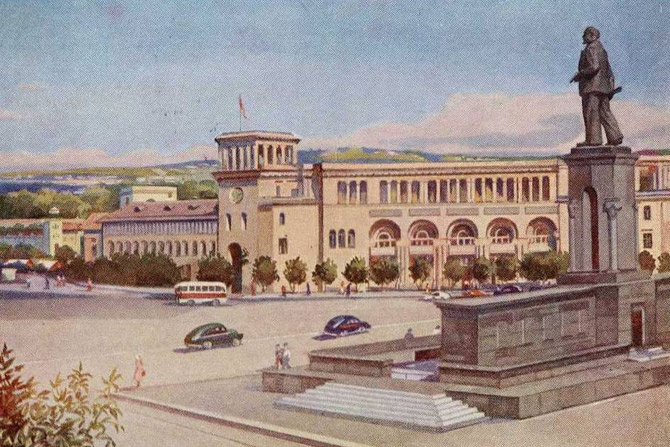

The changes in the urban landscape of Yerevan during the Lenin era began with the development of the city’s first master plan, designed by architect Alexander Tamanyan and approved in 1924. In 1932, the Russian-born architect relocated to Yerevan to head construction efforts in the republic and to implement the city’s new master plan. The plan was designed for a population of 100,000 residents.

According to Tamanyan’s Master Plan, Mount Ararat lies to the south of the city, with the Hrazdan River flanking its western edge. A clear, central green ring is evident in the plan, along with a main green-lined pedestrian parkway. This parkway begins on the eastern part of the plan, crossing the oval park, before making its way to the Hrazdan River. The oval park wraps around the city core, providing access to the green belts that were planted to surround the city. These green belts are commonly referred to as the “lungs of the city” by local residents.

“Regardless of the fact that back then ecological studies were not very advanced, the green ring and green belts were very important in the semi-arid climate, and in order for this to be a capital city the climate had to be changed, and that was done by planting the hillsides that surround Yerevan…and by adding fountains that were bettering the climate of the capital as they grew in number”. (Interviewee 2011)

The Republic Square is evident in this picture along with the Opera and Cascade leading to Victory Park, a section of the green belts that were planted on the hills around the city. Tamanyan argued for wider streets like Abovian, which were at the time too wide in scale for a city of Yerevan’s size. Tamanyan convinced the authorities that based on the environmental conditions of Yerevan the streets would have to be this size in order for them to have tree plantings that would sustain a capital city. (Interviewees 2011).

Tamanyan challenged the centrally-planned, overly-generalized norms administered by Moscow and provided arguments for locally-based solutions. Proposed widths of streets and medians, wide enough to accommodate street trees, would create a livable city based on the needs of the environmental conditions at the time. His ability to establish a city based on strong ideals and ecological justifications would create the foundation of a master plan that would only be modified slightly in future phases of the city’s development.

Tamanyan had innovative ideas for the new city. Inspired by the interesting topography of Yerevan and the hills that surrounded the city in three directions, he decided that the city should be oriented towards Mount Ararat. The city was to be an amphitheater with the Ararat mountain range as the terminal view (Interviewee 13, 2011). Ararat has long been a symbol of hope for the Armenian people, as expressed in a poem entitled Will by Armenian poet Hovhannes Shiraz:

“My son, what shall I will you, what shall I will you, my dear,

That you may remember me in coming sorrow or cheer?

I've no treasures, what treasure; treasure's the light of my eyes,

Only you are my treasure, you treasure of my treasures.

I want to will such treasure for you as your father that

In any other country to will a father cannot;

I am willing that to you which in our great century

Small men have imprisoned and also chained in the clouds;

I will you our mountain so that you take it from black cloud

And bring it home carrying it with our spotless justice,

So that you may throw my dear, even with your poor small paw,

To our side our mountain that's your justice's sea of strength,

And when you bring it, my dear, take my heart out of my tomb,

And toward the free above rise and take with you my heart,

And bury my heart under the snows of Mount Ararat,

So that in my tomb as well,

It won't be cold from the fire of longing for centuries.

I will you Mount Ararat, that you may keep forever,

As our language and also as your father's home's pillar.”

Hovhannes Shiraz, 1942

“Tamanyan understood the importance of Ararat in the national identity, and thus, he made it the focal point of the soon-to-be built modern city of Yerevan. He also aimed to create a capital city that would combine the rich natural landscape with the architectural movements of the time. The Garden City movement had garnered international attention and had made its way to the major cities of the Soviet Union. In embracing elements of the Garden City movement, Tamanyan’s plan would provide the ideal transitional urban landscape for Yerevan’s new population—an agrarian society which would now have to convert to industrial city living. In order to implement the plan, tree planting projects between 1928 and 1988 created 1,930 hectares of tree coverage in Yerevan, 11.4 percent of city land.” (Abrahamyan & Baghdasaryan, 2003)

“Tamanyan envisioned a city with a clearly defined axis, including an amphitheater that was oriented towards Ararat, many highways and two main arteries that would lead towards Ararat and Aragats.” (Hakopyan, 2008)

“Tamanyan’s Master Plan, though designed in the Lenin era, would not be implemented until the Stalin era. Intensive planting took place in the late 1930’s in the north west of the city. Two green belts were planted, one which was supposed to be 16 km long and 800 meters wide and the second that was to be 50 km long and 1000m wide, with a distance of 1-2 km in between.” (Danielyan, 2007)

Note: The interviewees quoted in the article are from field research conducted in 2011. Semi structured interviews were conducted with 20 civic society representatives to help answer questions pertaining to changes in the urban landscape of Yerevan. They include members of the academia, national parliament, local government, activists, historians, and journalists.

Sources:

Abrahamyan, V. and Baghdasaryan E. (2003, October 17). Yerevan's parks have been

seized by government officials. Hetq.am, np.

Danielyan, K. (2007). GEO Yerevan assessment of the local environmental conditions.

Yerevan, Armenia. Lusakan.

Dudwick, N. (1997). Armenia: paradise regained or lost? In I. Bremmer & R. Taras

(Eds.), New states, new policies: Building the post-Soviet nations. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Hakopyan, J. (April 1, 2008). Changing for the ages: Yerevan constructs a 21st century

face.ArmeniaNow.com. n.p.

Suny, R.G. (1993). Looking toward Ararat: Armenia in modern history. Bloomington:

Indiana UP.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment