90 Year-Old Dounya Sargsyan: After a Lifetime of Teaching, She Still Embroiders

The wall of 90 year-old Yerevan resident Dounya Sargsyan’s living room is awash with framed artificial flowers – carnations, roses, and others.

They are all signed – Dounya Sargsyan, 1925.

The senior citizen, born in Gyumri to a father from Sebastia and a mother from Kars, is an avid lace maker. Mrs. Sargsyan never married.

She removes two needle works, with tiny butterflies stamped on top, from a drawer. She will donate one to the Komitas House-Museum, and the other to the Armenian Genocide Museum.

Mrs. Sargsyan had donated 130 of her needle works to friends and churches over the past fifteen years. She makes notes in the calendar atop the table about who gets what.

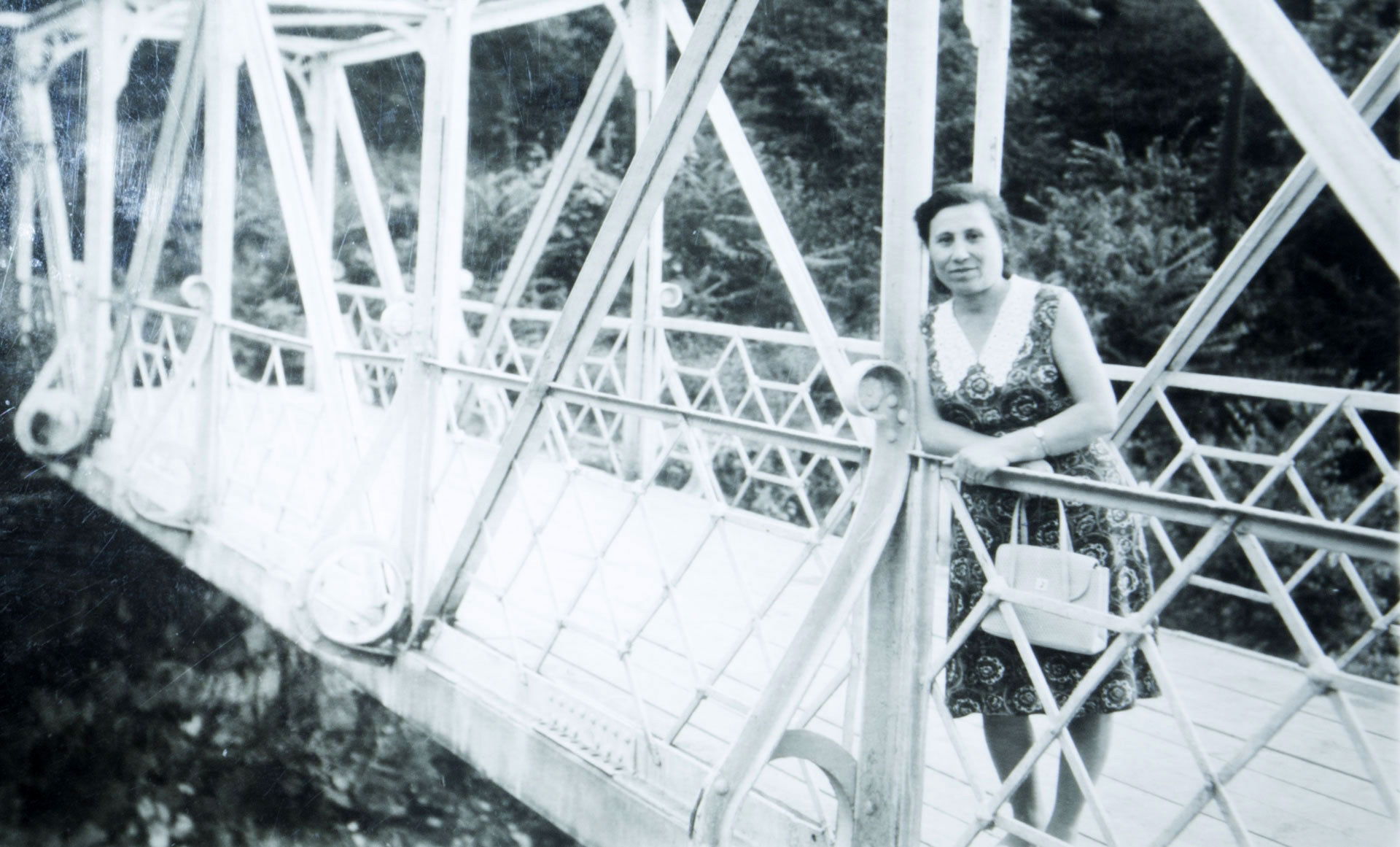

“I turned ninety on May 9 of this year. Let me get my photo album out,” she says while rummaging through the cluttered table. There’s a needle work pillow on the table, bags of thread, books, newspapers, and the stems of fresh herbs.

“I’m a bit flustered today. Friends came over to clean the windows. I can’t manage anymore, but I don’t want them to stay dirty. I’m a bit picky that way. I don’t like dirty things,” she says, opening the photo album.

Mrs. Sargsyan gives free needle work classes. Her fingers have grown crooked from years of sewing. She says she can no longer work with fine thread. But work she must.

She removes some clothes from the wardrobe. Most of what she wears, Mrs. Sargsyan has sewn herself. “I can’t sew anymore due to my fingers,” she says looking at the clothes. She goes on to say that she even altered clothes purchased from the store and that at school everyone was amazed that she stood out because her clothes were different.

“See this dress? I sewed it for our school’s tenth anniversary. It took me two days. Can you imagine?” she says smiling.

At ninety, Mrs. Sargsyan speaks slowly, the words are drawn out. Sometimes she can’t hear us. She apologizes.

At ninety, Mrs. Sargsyan speaks slowly, the words are drawn out. Sometimes she can’t hear us. She apologizes.

She grew up in a family of six – three boys and three girls. She and her sisters learnt needle work from their mother. When they were going to school, they helped their mother by making sheets and pillows.

While in the 6th grade, Mrs. Sargsyan worked at the Gyumri turnip collection facility. She worked the scales, weighing the produce. She devoted her evenings to needle work.

She says that she always liked math as a pupil and dreamt of enrolling at the institute after graduating, but her father hadn’t returned from the WWII front.

“I had to help my mother, so I continued working,” she says.

It turns out that Mrs. Sargsyan graduated from the physics-math department at Gyumri Teachers Institute and continued her education in Yerevan. She worked as a mathematics teacher until 1999, first in the village of Akhourian and then in Yerevan. For a few months she stood in for the domestic sciences teacher.

She makes a point to stress this, adding that she taught the girls embroidery and sewing repair to boys. “It would definitely come in handy in the army,” she says.

Arthritis in the feet and hands forced her to leave teaching. “When I retired from teaching, I started to do embroidery at home,” she says.

She again goes to the chest of drawers, which is full of her work. “I’ve done all types of embroidery. See here, it’s the container for my nightgown. I’ve written the first letter of my name,” Mrs. Sargsyan says, laying the dress on the bed.

She then points to two large photos above the bed. “It’s my brother and me in my youth,” she says letting out a sigh.

Her brother worked at the train station. The family was given a metal trailer to live in. “My brother fell under a train and was killed,” she says.

The spinster says she received a marriage proposal at the age of sixty but turned it down. “After all that time, was I about to get married at sixty?” she asks.

When a colleague told her that if she didn’t marry she would remain alone for the rest of her life, Mrs. Sargsyan turned around and replied that she would always have visitors, her pupils and friends.

The senior citizen’s one wish is to get her 17,000 dram ($36) monthly social allowance reinstated. Mrs. Sargsyan says that in 2004 the law was changed so that people with heirs would no longer be eligible. In her case, her heir is her sister’s daughter. The woman now makes due on a monthly pension of 60,000 drams. She says is barely covers her utility bills.

After putting her clothes back in the chest, Mrs. Sargsyan starts talking about conditions in the country, noting that those in charge should be a bit more conciliatory towards one another and should jointly think about the plight of the people.

“But they grab all for themselves and things are getting worse. That’s my opinion,” says Mrs. Sargsyan.

She smiles and looks at us. “I’d like to see less of our girls naked on TV, all that singing and dancing. It’s defilement. What have they turned us into? I can’t take it anymore. I call on God to take me. I am a person of another century, not this one,” Mrs. Sargsyan exclaims.

As the conversation ends, she offers us some chocolates. We politely refuse. Mrs. Sargsyan is adamant, “you must take something!”

We laugh. She then tells us to visit her again and again.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment