Armenia’s Institute of Physiology: Creating Scientific Innovations Yet to be Implemented

Marine Martirosyan

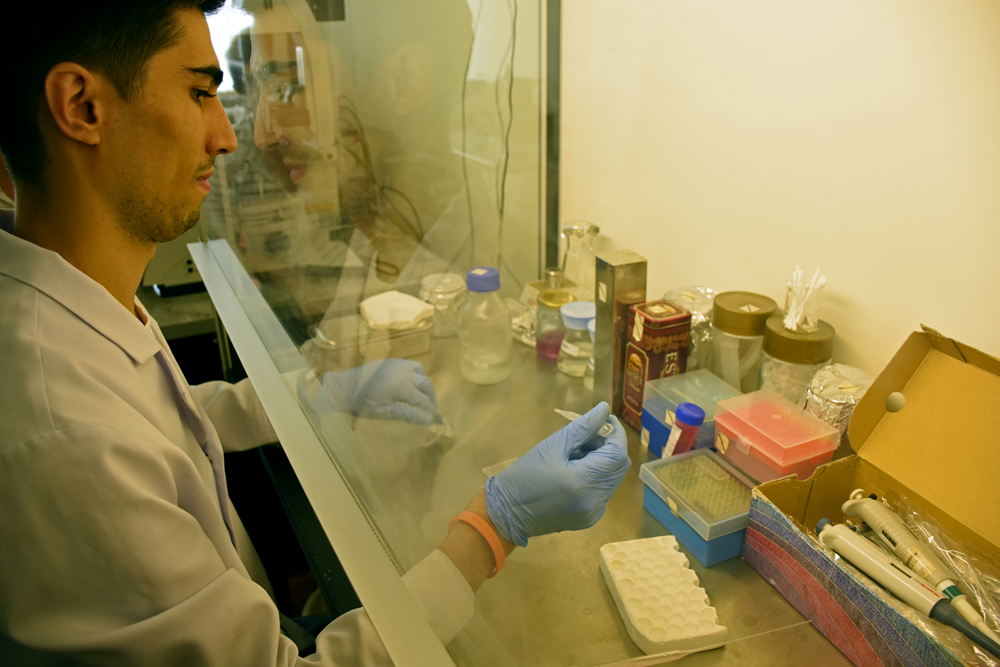

Vahe Sarukhanyan

Founded in 1943, The Institute of Physiology of the National Academy of Sciences of Armenia, in Yerevan, is a research center waiting for its innovations to see the light of day.

The lack of adequate government support and the reluctance of some in the sciences to reinvent themselves and their institutions to meet a host of modern day challenges are a large part of the problem.

Renamed in 1959 to honor the work of the prominent scientist Levon Orbeli (creator of the theory of evolutionary physiology) in establishing the institute, it is now trying to recoup some of its former prominence of the 1970s and 1980s.

Doctor of Biological Sciences Naira Ayvazyan has been the institute’s director for the last five years. Her term has expired, and she’s going to run in the upcoming elections for reappointment.

Levon Orbeli's legacy

The founding of the institute is closely tied to Levon Orbeli. Ayvazyan says that there were very good schools in Armenia in the 1940s. That was when Levon Orbeli came to Armenia together with his younger brother Hovsep and decided to establish the Armenian branch of the Soviet Academy. Several scientific institutions were included in the academy, one of them being the Institute of Physiology.

Since Levon Orbeli was mostly staying in St. Petersburg, the Institute of Physiology was lead more by his pupils. The Armenian Physiological Society then sent a letter to the academy asking for a permanent director. In response, one of Orbeli's pupils was sent to Armenia, and the institute was also provided with modern technical assistance.

Ayvazyan says that’s when the institute started to prosper. In the 1980s, the Orbeli Institute was the leader of the neurophysiological research in the USSR. In those years, the institute had more than 250 employees, but after the collapse of the USSR, in the 1990s, there was some decline.

Ayvazyan says that though their database became outdated, they attempted to solve advanced scientific issues, and they succeeded due to their links with scholars and post-graduate students who had moved abroad.

In the last 7-8 years, the institute has been able to restore its previous academic ties with its foreign partners, and has succeeded in equipping the institution with some unique equipment via local and international grants.

Reduced staff, unused capacity, minimum wage

The institute is located on Yerevan's Orbeli Brothers Street. It moved there in the late 1950's.

When the staff expanded in the 1980's, a new building was built next to the old one. The institute has a vivarium where mice, rats, rabbits and frogs are stored for experiments. They used to experiment on dogs, too.

Armenia’s government has now allocated four floors of the 1980s building to the State Committee of Science and the National Center for Professional Education Quality Assurance Foundation.

"We no longer experiment with dogs, as European ethical norms do not allow it. It is possible, but the requirements and permits are too strict. However, there is no need any more, because now there are tissue cultures and other models that can show the same effect. " Ayvazyan says.

|

|

To take part in grant projects, the vivarium should be licensed. The director says this is one of the reasons for Armenia’s research and experimental institutes falling behind in grant schemes.

The institute has been renovated over the past five years, and now has central heating.

The number of employees has dropped from 250 in the 1980s to 115 today. The director says the number of employees has increased during the last five years, and they’ve tried to hire young people.

"We prefer to take interns from the universities, to make them specialists, because our universities do not give the basics for a person to become a valuable employee," Ayvazyan says.

Some 80% of the employees receive a minimum monthly wage of 55,000 AMD ($114). The director receives 98,000 AMD, the highest monthly salary. Despite the meagre wages, young people come to apply for various grants and get training abroad.

In 2016, the government of Armenia allocated 127,309,000 AMD ($266,320) for infrastructure maintenance and development, and 13,400,000 AMD for targeted research programs.

The institute also receives grants from local and foreign organizations.

2014- 36,312,600 AMD (7 items)

2015- 25,788,400 AMD (6 items)

2016- 25,401,400 AMD (5 items)

The grants were given by German Volkswagen Stiftung Foundation, the EU TEMPUS Project, the SCA and the Armenian National Science and Education Foundation (ANSEF).

Scientists are in “idea” business

Ayvazyan says that scientists are underestimated in Armenia.

In response to the observation that the government does not know what's happening in this area and that science is somewhat isolated, the institute director says that while there perhaps is a shortage of scholars in Armenia, it is also necessary to understand the mentality of those engaged in science. She claims many are "repressed” and want to deal with their work solely, rather than writing papers and opening doors to different recipients.

Armenia’s current prime minister, for example, periodically argues that science should give practical results.

While Ayvazyan agrees that science should serve people, but if the fundamentals do not develop, the application does not have any grounds. Accordingly, the number one goal of a scientist is an idea, that is to say, of course, the institute can also have a small workshop and produce products, but that is not the function of an academic scientific institution.

Ayvazyan cites the example of the Weizmann Institute in Israel, some of the scientists of which have received Nobel Prizes. "They develop a prototype and give it to a pharmaceutical company, which makes the prototype a product and produces. It's a normal process.”

The Institute of Physiology’s innovations - artificial skin, lie detector and antivenom technologies

Director Ayvazyan says that if there’s appropriate funding, they can produce artificial skin that can help in case of different pathologies such as trophic ulcers. The innovation can be useful for the army. Ayvazyan says several projects have been submitted to the government and they have also applied to different funds to try all the options.

One of the institute's twelve laboratories examines human psychophysiology. They use a polygraph device, known as a lie detector, to test the reactions of individuals.

"The device takes the physiological data of a human being and creates a psychological picture," says Ayvazyan. "We can perform a professional fitness examination, which is very important for sportsmen and military pilots." They tested it with a number of cadets, expecting further cooperation, and they also cooperate with the Institute of Physical Culture.

The Laboratory of Toxicological Research, also headed by Ayvazyan, works on producing a snake antivenom. Common throughout the world, it has never been produced in Armenia.

There are snake species native to Armenia, but antivenom is brought from Uzbekistan, where the venomous vipers are different. Uzbek antivenom is polyvalent: it’s not only used for viper bites, but also for other types, such as cobras, which doesn’t exist in Armenia.

Ayvazyan says that the creation of antivenom specific to Armenia’s snake species is near completion and funding.

She says that it would cost $200,000 to launch an antivenom project that would take care of Armenia’s needs.

Ayvazyan adds that the government has been offered two options: either establish a proper modern production to benefit the state, or start small-scale production at the institute.

An outside observer notes challenges faced by sciences in Armenia

Professor of Pharmacology and Physiology Narine Sarvazyan (George Washington University, U.S.) has come to Armenia for four months to conduct practical English language courses at the Institute of Physiology.

Sarvazyan’s lab at the university’s School of Medicine and Health Sciences, is interested in the basic mechanisms of arrhythmias, tissue engineering, and stem cell based cardiovascular repair.

Professor Sarvazyan, who left Armenia in 1991, says the lack of science funding in Armenia is a well-known fact.

For example, a young scientist who earns 70,000 drams must find another two or three jobs to live a normal life, while young scientists in the U.S. are engaged in science most of the day.

Along with the need for new equipment, Armenia faces the challenge of employing younger scientists. Many “established” older professors do not want to make way for a new generation of scientists. They prefer to go on occupying their positions and getting a salary

"The next important issue is school education,” says Sarvazyan. “Especially in the provinces, there are often no qualified teachers of mathematics, physics and chemistry. When a child doesn’t learn these subjects at school, it presents problems later. The government also needs to support teachers. I do not think that we have problems with the gene pool in Armenia. The problem is how to effectively manage the resources at hand. It will be more effective to give young people the opportunity to work because they have a greater desire and drive.”

Photos: Narek Aleksanyan

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment