Comrade Beritan

I am lying down on a sleeping bag right near the stove. I have two pairs of eyes staring at me: Ocalan's eyes from the right and a young freedom fighter's eyes from the left. The stove is already off, it is cold here. Some beams of the kitchen light have found their way into the room from under the door and are dimly lighting the images.

Their eyes oppress me. I close my eyes not to see them but feel them nevertheless. Especially the eyes of the young man. His name is Maslum Dokhan. This afternoon Beritan told me about him.

"Our comrade Dokhan was very intelligent, he would read a 500 pages book in a day, learnt every nation's history. He was a comrade-in-arms of our leader. He was 20 or 21-years-old when went on a 72-day hunger-strike for the Kurdish nation. On March 21, on the day of Newroz, he burnt himself alive. He had just three matches with him."

"But our leader is against suicide," Beritan added, "He says to work for our independence, get education, learn history. You will never achieve anything by killing yourselves."

When Beritan speaks about "our leader" Abdullah Ocalan, her melancholic eyes, absent from this world, shine. She calls me a comrade. Everyone in this village calls us comrade.

Alagyaz is the biggest Yezidi village in Aragatsotn Marz. But the villagers say they are Kurds by nationality and Yezidi by religion. They do not leave me any room to doubt; the villagers speak Kurmanji, a Kurdish dialect and watch a Kurdish TV channel called Roj TV, and almost everyone has posters or pictures of Ocalan.

The room where I am trying to sleep now is the Kurdish Office at Alagyaz's Kurdish Cultural Center. Beritan created the Center through her own and her brothers' efforts alone. It consists of a corridor-kitchen, the Kurdish office, a museum and medical clinic. The rooms on the second floor are for guests.

There is a range of sleepers in the corridor; no one enters the center in street shoes.

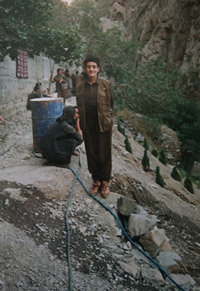

Beritan runes the Center alone. She was born in Alagyaz, graduated from medical university in Yerevan, and worked five years in the Yerevan State Reanimation sector as a nurse. In 1999 she left for Iraqi Kurdistan, where she spent several years in the mountains as a doctor and a nurse.

"In 2004 I was back in Armenia. The village was in a very bad state, especially in terms of medical care. Alagyaz is the center of some10-11 Kurdish villages. In winter these villages are totally cut from the rest of the world. So I decided to open a medical clinic here. The office and the museum were opened at the same time. It was convenient for me to have all of them together in one place; otherwise I would not have time to look after them."

In the Kurdish office, there are several copies of Mezopotamiya , an Armenian-language Kurdish newspaper lying onh the table. There are books on Kurdish culture, folklore, and history as well. Beritan's mobile phone caught my eye; it had a picture of Ojalan on the screen.

There are other freedom fighters aon the wall,. besides the posters of Ojalan and the young guy. They are mostly men with moustaches, with only two women here among them. One of them is very beautiful.This afternoon Beritan told me about her as well. Her name is Via Soran; she also burnt herself alive, Beritan said, in a sign of protest again Ocalan's arrest.

"And our comrade Zilan (another woman) tied a bomb to her belly and, pretending to be a pregnant woman, went among the Turkish soldiers and blew herself up. She in 1996, when the Turks wanted to execute our leader."

"Beritan is also the name of a hero. Comrade Beritan was a Kurd from Turkey. In the battle between Iraqi and Turkish Kurds he alone fought against 500 wariors. They offered him the chanced to surrender, promising to grant him his life but he shouted out, "Shame on you! Instead of fighting for our freedom you are fighting against each other!" and threw himself out of the cliff. When I read about his deeds I decided to bear his name."

"Beritan is also the name of a hero. Comrade Beritan was a Kurd from Turkey. In the battle between Iraqi and Turkish Kurds he alone fought against 500 wariors. They offered him the chanced to surrender, promising to grant him his life but he shouted out, "Shame on you! Instead of fighting for our freedom you are fighting against each other!" and threw himself out of the cliff. When I read about his deeds I decided to bear his name."

Beritan's real name is Fryaz. Fryaz Avdalyan. But the villagers call her Jamila.

"I liked that name since childhood and prefered to be called Jamila, so that name stayed with me," Beritan smiled.

All day today Kurdish Roj TV was on in the office. If I weren't so lazy I would get up and turn the TV on even now, would turn the volume low so as not to disturb the others and would enjoy Kurdish rebel and love songs.

The others are sleeping in another room, which is also the museum. The museum is the inner sanctum of the Center. Entering it, one has to remove even one's slippers. Some of the objects in the museum were in Beritan's family; others she found in different villages.

"The Center first of all was created for cultural purposes," Beritan says. "The Kurds are an old nation; our culture is one of the ancient cultures and we have to preserve it. As far as I know this is the only Kurdish museum in Armenia. Researchers on Kurdish culture from different countries always come here."

National dresses, carpets and knitting called emeni have centuries of history. In the village it is still possible to meet a woman in national dress. But only old women. As for carpetry, the Kurds in Armenia no longer do it.

A Kurdish national musical instrument, a kyamancha, hangs on the wall.

"Armenians claim it is their national instrument, Kurds claim it is theirs," Beritan laughs. "The culture and lifestyle of our nations are very similar."

Some displays are still used in the cultural festivals and holidays held here. They mostly are devoted to freedom fighters' days.

It is pretty cold in both in the museum and the clinic. But we are lucky; the villagers say just a week ago it was snowing heavily here. Now we have beautiful sunny weather outside.

The medical clinic handles 11 Yezidi and 9 Armenian villages. Beritan usually is able to provide first aid. But in some cases, say in case of intoxication, she does not have the necessary facilities.

The medical clinic handles 11 Yezidi and 9 Armenian villages. Beritan usually is able to provide first aid. But in some cases, say in case of intoxication, she does not have the necessary facilities.

Today a girl from a neighboring village who came to have her tooth pulled out. She sat on an ordinary chair; there was no sign of the facilities I was used to seeing in my dentist's office. With a little help from her friends Beritan purchased sterilization equipment and devices for checking diabetes and blood pressure.

There is a polyclinic in Tsakhkahovit, another village in the Aragatsotn Marz. But many villagers have trouble getting there, especially in winter when the roads are closed.

"The people who have been to my clinic and the polyclinic say mine is much better in terms of both cleanness and service," Beritan says.

The polyclinic pays Beritan 20,000 drams per month. She spends almost all of it immediately, in the chemist's shop near the polyclinic.

"In the past I didn't take money from the patients," Beritan says. "My brothers would help me to make ends meet (One of Beritan's brothers is a teacher of mathematics; another works as a physicist in Moscow). But now everyone who can afford it pays for the treatment."

Last year Beritan applied to the International Committee of the Red Cross with a request to provide the post with the necessary facilities. She says, Red Cross denied bringingb the reason that they are very busy with Karabakhi war's veterans.

It has gotten colder. I am not thinking about th heros who burnt themselves to death. I am thinking about the living hero Jamila-Beritan-Fryaz, who is only 35 and has completely devoted herself to helping others. I do not write "sacrificed herself" because she does not think so and denies any words of praise or admiration addressed to her.

From September, Beritan is going to be a student in the Medical Department of Hay Busak University.

"To be more knowledgable and useful to the villagers," she says.

Photos by Onnik Krikorian

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment