Ebru – Weaving the Myth of a Europeanizing Turkey – 2

There is no need to prove that the vast majority of who is photographed, in comparison to the photographer (and the other project authors) is on a very low level of existence, if we can ascribe any social level at all, say, to the Sarikecili tribe living in the Taurus Mountains. This difference consists of numerous composite elements, but in this case what is more important is who has the occasion to represent the other; to photograph and tell stories.

This privilege is a benefit to those who are looking for a new language “to make cultural diversity in Turkey visible and intelligible” via the Ebru project (one can also add controllable: knowledge/power relationship). At the same time, it is obvious that “cultural diversity”, deprived of historical-geographic depth – also through the magic word ebru – frequently becomes a euphemism for those ethnic, religious and social conflicts and contradictions that are in abundant supply in Turkey today.

Turkey’s European prospects, that Ebru wants us to believe, those ideas, values and beliefs related to this prospect that the project participants, in this or that way, identify themselves with, convey definite orientalist underpinnings to the project. The representation of ethnicities and their cultures as “reflections” remove them from the cultural context, depriving them of local traits and history. They need a western gaze to be represented, to validate their existence. According to Durak, it’s as if the people looking at his camera lens wanted to say, “We exist and we are here.” For Berger, those cultures (tribal groups) are equated to the elements of nature, where love and hate, the same and the other, the eternally repeating mix and transformation are “natural” prehistoric realities, free of social and political conflicts and objectives.

Turkey’s European prospects, that Ebru wants us to believe, those ideas, values and beliefs related to this prospect that the project participants, in this or that way, identify themselves with, convey definite orientalist underpinnings to the project. The representation of ethnicities and their cultures as “reflections” remove them from the cultural context, depriving them of local traits and history. They need a western gaze to be represented, to validate their existence. According to Durak, it’s as if the people looking at his camera lens wanted to say, “We exist and we are here.” For Berger, those cultures (tribal groups) are equated to the elements of nature, where love and hate, the same and the other, the eternally repeating mix and transformation are “natural” prehistoric realities, free of social and political conflicts and objectives.

Susan Sontag, noticing that photography reinforces the impression that social reality is comprised of small, unrelated units, continues, “Through photographs, the world becomes a series of unrelated, freestanding particles; and history, past and present, a set of anecdotes and faits divers.” In the Ebru exhibition, the ethnicities and tribal groups so presented are faced with the imperative of becoming “visible and intelligible”.

Recounting the observation of Brecht that the photograph of the Krupp factories reveals virtually nothing about the organization, Sontag concludes that “understanding is based on how it functions. And functioning takes place in time, and must be explained in time. Only that which narrates can make us understand.” But it is understandable that a narrative also cannot be free of the biases of concealment and misrepresentation. A representation, whether visual or narrative, can never be “innocent”, thus the construction of meaning through representations – and the struggle for meaning – has an undeniable political dimension.

The photographs

One could have expected that such a photographic project, given its grandiose pretensions, could possess a certain, perhaps not clearly formulated conception of photography. As I have already observed, here the photographs are firstly “reflections”, “witnesses” of Turkey’s cultural diversity. They also testify to the existence of ethnic groups in various reaches of Anatolia; their suffering and will to survive.

On the other hand, the photos are called on to reflect “that profound love and respect” that the photographer (and others) feel for “the people of his country” and to also convey “the beauty of diversity within so much affliction, sorrow and pain.” Let us remember that it was envisaged for the photos to become small units from which the photographer would be able to construct his story. And it is a story about Turkey, about its “today”, while also “reflecting the sorrows of yesterday and the hopes for tomorrow.”

This is a Turkey which, at least in terms of the anticipated prospect, is presented as the homeland of all its ethnic-religious groups. In a word, that which is clear from the start, the love and concern of the photographer for his homeland. And we must accept that only the alchemy of patriotism is able to extract the beauty of diversity from that much suffering and sorrow.

Thus, a photograph reflects (is called on to reflect) that which already exists; transfers prepared meanings and intentions freely. Not one word regarding the photographic image, as being codified by a cultural context and ideologically charged.

Hundreds of photos of the exhibition are subject to categorization, at least formally, according to three criteria that we find in their inscriptions – ethnos (religion, race), residence (and where the photo was taken), and the date of the photo (ex. Hamshen, Chamlihemshin, August 2003.)

Of course, we can find different manners of classification. For example by the site where the photo was shot – landscapes, homes, in the house, at the entrance or yard to the house or photos taken in public spaces. The photos can be divided by the number of people photographed – an individual, a couple, small groups (including families, and here the gender and age make-up of the family is important), large groups. The gender and /or age of those photographed can serve as the base of the classification – women, men, mixed groups and, on the other hand, children, youth, old people, individuals of various ages…None of these principles and, in the first instance, grouping according to ethnic-religious affiliation and place of residence, wouldn’t merely be formal. It can reveal things that both the photographs and the project’s texts remain “silent” about. Why are there so few landscapes and so many photos taken inside the home or in the yard, especially near the door? Why are there so many old people and so few youngsters? Naturally, to formulate such questions and to search for answers one must possess demographic, economic, political and other information.

Of the more eye-catching signs that one can spot in these images are those testifying to the fact that individuals are in the process of being photographed. More often than not it is a smile that, however, can have very different nuances and meanings. These signs are not only the result of the extent to which the practice of photography, taking photos and being photographed is a part of the everyday life and activities of these people, but also who is taking the photos and to what purpose – how the photos might be used, etc.

In this context, of course, a more striking sign is the absence of those individuals who, as the photographer recounts, refused to be photographed – out of an inborn fear of publicly displaying their identity. Here we are not talking about personal identity but ethnic-religious identity (the ethnicization of the person and personalization of the ethnicity). In Turkey, ethnicity (religion), ethnic affiliation, determines ones destiny. A Yezidi that meets Durak curses his fate: the fact that he was born a Yezidi and for decades has “no religion” according to his identification card.

The Hamshen woman

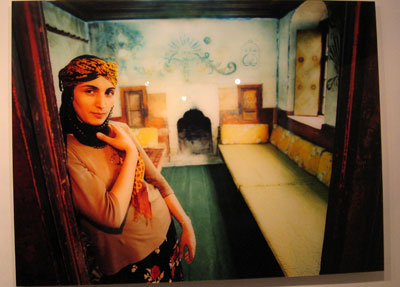

The above mentioned inscription (Hamshen, Chamlihemshin, August 2003) in particular refers to the photo appearing on the front page of the jacket cover of the abridged book of the project and on the poster for the Yerevan exhibition. It’s also the opening photo in the ACCEA exhibition that a visitor sees when entering. In my opinion, to start a preliminary discussion of the photos, it wouldn’t be incorrect to pose these types of questions – why was this photograph selected, what advantage does it have and would other pictures have served the same aim? (I believe there were at least another ten more interesting photos in the exhibition). Anyway, it wouldn’t be wrong to assume that this photo, in some way, reflects (using a favorite term of the photographer) or expresses the motives and intentions of the photographer and the entire project.

The above mentioned inscription (Hamshen, Chamlihemshin, August 2003) in particular refers to the photo appearing on the front page of the jacket cover of the abridged book of the project and on the poster for the Yerevan exhibition. It’s also the opening photo in the ACCEA exhibition that a visitor sees when entering. In my opinion, to start a preliminary discussion of the photos, it wouldn’t be incorrect to pose these types of questions – why was this photograph selected, what advantage does it have and would other pictures have served the same aim? (I believe there were at least another ten more interesting photos in the exhibition). Anyway, it wouldn’t be wrong to assume that this photo, in some way, reflects (using a favorite term of the photographer) or expresses the motives and intentions of the photographer and the entire project.

The photo depicts an attractive young woman. She is inside the house, leaning on a doorway. In the background is a traditionally furnished room. In the garments she is wearing one can spot traditional elements (head covering) and clothes that are devoid of any prominent traditional signs. She comfortably gazes at the photographer in front. The colors of the woman’s clothes, of her face and hands, are in harmony with the room’s interior, which impart a balance to the picture. However this balance is skewed due to the angle between the frame of the photo and the door frame as well as the slant of her body that is slightly turned toward the inside of the room.

Let us separate out two basic elements that define the photo – who is photographed (the subject, individuals, their ethnic-religious affiliation, even though here the “Hemsinli” isn’t all that clear, as well as the age and gender), and where (outside, interior, doorway to house, in the yard, etc). The photo of the young Hemsinli woman is unique in several ways. She is alone in the house (with a foreign male photographer; let’s remember that commonly in traditional societies the woman comprises the core of ethnic resistance against foreign domination and her visibility was restricted by several means) leaning comfortably on the door frame and nothing, not her posture, smile or anything else speaks about her confusion or being up-tight. The photo is not only unique for the positioning of her body and head, but also her hands. I didn’t find a similar pose in any other photograph.

Standing in the doorway and looking out can be interpreted both as being open to a foreign gaze and as being ready to be free of the traditional room environment. The coupling of the traditional elements of her garments and, in the first place, her head coverings, with her altogether non-traditional pose, suggests a prospective of emancipation. The picture narrates about a certain type of femininity and, being included in that narrative, the tradition is transformed into the signs of the traditional and mixed with the codes of sexiness that are globally available through the media.

On the other hand, the woman’s confidence and emancipation do not result in self-confidence. Passivity is clearly expressed in her posture. Janice Winship has shown all the different ways the hands of men and women are shown in advertising photographs. If the hands of men are usually shown to be active and controlling, the hands of women are represented as decorative and caressing. These are how the hands of the Hamshen woman are, conveying a clearly underlined degree of passivity to her. (It is possible from this viewpoint to compare the photo of the Hamshen woman with that of Durak’s portrait appearing nearby in the exhibition catalog.)

Now let us see what alternative possibilities, in terms of the picture’s subject and site, are afforded by the exhibition’s diversity. Using the language of semiotic analysis, let us observe two paradigmatic sets. In the place of a young woman, an old woman, a girl, can be depicted, an old or mature man, a husband and wife, or friends (mostly old), a family, different types of groups…Then too, the photo could have been shot not inside the house but in the doorway or at the entrance, in the yard or in the countryside.

Not having the possibility of discussing the noted versions in detail, I believe it is sufficient to note how different the other two selected photographs for this article are – taken in the Taurus Mountains. I have already noted the existing signs in the pictures that testify to the presence of the photographer, reminding one of what type of communication has been established between the photographer and those being photographed. In many cases their mutual understanding is far from complete. Frequently, instead of inclusion and inspiration, one can read alienation and resistance in the picture.

Remember that here the Hamshen woman (on the book jacket and exhibition poster) represents not herself (we don’t even know her name), and also not only Hamshen people, but rather Turkey’s cultural diversity; more correctly – ethnic-religious minorities. This equating of these minorities with the woman is one more expression of the deep-seated evident orientalism of this project. The picture of the Hamshen woman, concealing the great diversity of the photos (and the cultures behind them) and the prominent differences, inspires the openness of these cultures, the desire to change and passivity at the same time. In reality, while becoming visible, being deprived of a historical-geographic context and possessing not one possibility of counteracting the dominant forms of representation, these cultures are surely on the path towards vanishing.

If my interpretation is close to being credible, as I believe, than this photo stands so clearly apart from the others and so correctly conveys a few of the important intentions of the project, that I am on the verge of believing that it was carefully crafted, “staged”. True, the photographer stresses that he never attempted to “stage” any picture. (The first time I saw the exhibition’s promotional poster, my impression was that the woman was standing in front of a mirror and that the reflected picture was shown in the photo. This was reinforced by the word “reflections” appearing in the exhibition’s title. It was further evidence for my assumption of the photography being staged.) Nevertheless, John Berger once observed that, “What eventually distinguishes ‘very memorable photographs and the most banal snapshots… is the degree to which the photograph makes the photographer’s decision transparent and comprehensible.”

Photos:

1. Sarikecili, Taurus Mountains, June 2004

2. Sarikecili, Taurus Mountains, June 2004

3. Hamshen, Chamlihemshin, August 2003

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (1)

Write a comment