Monte Melkonian: November 25, 1957 - June 12, 1993

November 25, 1957 (Visalia, California) – June 12, 1993 (Artsakh)

What follows are excerpts of an interview given by Markar Melkonian, Monte’s brother, to the Voice of Nor Serount newspaper of London, 2005. Hetq has chosen those that provide some insights into the formative years of Monte’s early life.

Voice of Nor Serount: The London publishing house I.B. Tauris is coming out with your book, My Brother’s Road. Please tell us something about the book’s contents.

Markar: My Brother`s Road is a biography/memoir about my late brother, Monte Melkonian. Monte was a third-generation Central California boy who abandoned a promising career as an archaeologist to become an Armenian militant.

He was a witness to revolution in Iran, an Armenian militiaman in Beirut, an “armed propagandist” in Europe, a guerrilla fighter in southern Lebanon, a prison strike leader in France, and finally, a commander of 4000 fighters and thirty tanks in Mountainous Karabagh. He died in battle on June 12, 1993, and has since been designated a national hero of Armenia. My Brother’s Road traces the long journey of his short life.

Voice of Nor Serount: Could you tell us something about your family’s history, in brief? When did your predecessors (your parents or your grandparents) immigrate to America, and from whence?

Markar: Our father’s father was a shepherd and a bonded laborer from Kharatsor, a small village near Kharpert. His name was Ghazar. His wife, my paternal grandmother Haiganoush, was a village girl from an impoverished peasant family. In 1913, Ghazar, his wife, and the two of their five children who had not already died of tuberculosis sought asylum on a French ship and made their way to the United States. They became farm laborers in Fresno County, where my father was born.

My maternal grandfather, Misak, was from the town of Marsovan (today’s Merzifon), near the Black Sea town of Samsun, in Turkey. He was from an urbanized petty bourgeois family, but they were economically vulnerable. In his late teens and early twenties, Misak became active in the Hunchakian Party. Ottoman authorities imprisoned him at least twice, and he was ordered to leave the country of his birth. He was lucky to escape with his life. Eventually, he ended up in Fresno County, where he became a small farmer and raised a family. Our mother was his only daughter.

Voice of Nor Serount: My Brother’s Road is a biography, the story of the road Monte travelled. Please tell us something about your brother’s adolescence and his school and university days.

Markar: Monte was a bright student, a good baseball player, swimmer and runner, and the first elected president of his elementary school. He was a tough kid, too, the first one to dive off the highest rock into the river. At the age of fifteen, he went to Japan and stayed with friends there for a year. He studied the language and history of Japan, as well as karateand kendo, Japanese classical sword fighting. He visited Vietnam just before its liberation, and stayed for a short while in a Buddhist monastery near Seoul, Korea, where the abbot presented him with a robe and a Buddhist name. This, too, was part of his formal education.

Monte entered the University of California at Berkeley in fall 1975 as a Regents Scholar, with a double major in history and mathematics. He was impatient to graduate from university early, so he soon switched to a major of his own design, in Ancient Asian History and Archaeology. In the summer of 1977, when Monte was not yet twenty years old, he joined an archaeological field party in the Nevada desert, excavating Northern Paiute and Panamint Shoshone artefacts.

Monte earned money for college by working at odd jobs, applying for academic scholarships, and taking trips to Burma and the Thai-Cambodian border to buy rubies for buyers in the United States. He completed his undergraduate studies in less than three years, wrote his honours thesis on Urartuan rock-cut tombs, and was accepted for graduate work at Oxford University. As things turned out, though, he never attended Oxford. Instead, he re-enrolled in the school of life, the school of struggle and resistance.

Voice of Nor Serount: Monte was a native-born American, raised and educated in an American environment. Within Monte’s inner life, when and under what conditions did he wake up spiritually, to become the exceptional, selfless patriot that we know him as?

Markar: I suppose the closest thing to a dramatic awakening of Armenian patriotism in Monte took place on June 12, 1970, when our family paid a brief visit to our mother’s ancestral town of Merzifon. Monte saw the church where his great grandfather had been buried. It had been converted into a cinema house, and was festooned with movie posters. He also stood on the street and stared at a house that had belonged his mother’s side of the family before the genocide. Chapter Two of My Brother’s Road consists in large part of a description of this visit.

|

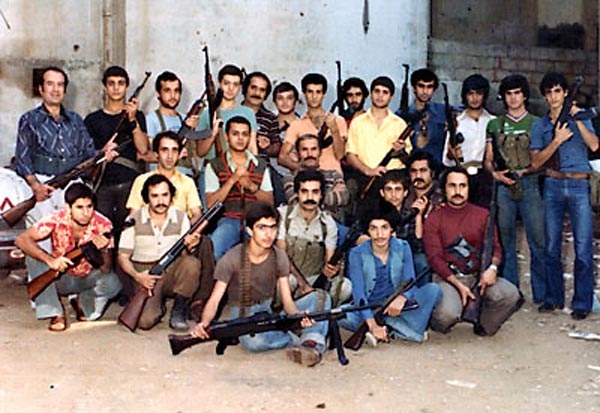

Monte (second row, on the left), with fellow Armenian militia fighters in the Naba'a |

But I doubt that Monte ever really had a sudden dramatic realization that he was Armenian—whatever that may involve. Remember, we were products of small town Cold War America. Like our playmates and classmates, we were imbued with the assumption that America, One Nation under (or perhaps even over) God, was an exceptional nation on a divine mission to uplift the world. We learned that Yankees, not Armenians, were God’s Chosen People. Somewhere along the line, however, Monte grew tired of American exceptionalism. Perhaps it was when he learned that the Yokut Indians of our San Joaquin Valley had not evaporated like dew, but had been annihilated in a “war of extermination,” as California Governor Peter H. Burnette called it in 1851. In any case, by his mid-teens, Monte had enough brains and enough experience to have figured out that most people on earth were disenfranchised and downtrodden. And that included Armenians.

|

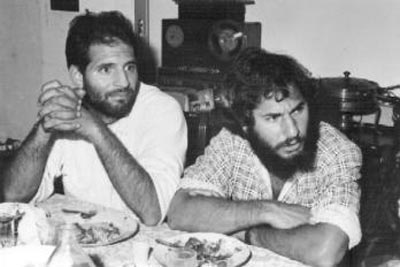

| Monte, aged 21 (right) with Markar in Beirut 1979 |

|

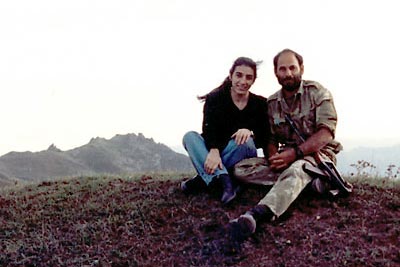

| October 1992. The commander and his wife Seta in Martuni. |

Monte loved the unique things of Armenian culture, of course—music, architecture, poetry, proverbs, and food. But in adulthood, he used to say Menk normal jhoghovoort mun enk, “We’re a normal people.” Fellow Armenians have misunderstood Monte when it came to his love of things Armenian. By identifying himself as an Armenian first, Monte never thought he was thereby enrolling in a peculiarly gifted and cosmically oppressed tribe. On the contrary, by embracing an Armenian identity, Monte was consciously rejecting the notion of a Chosen People, and aligning himself with the majority human population of planet Earth in the twentieth century.

People have asked me how it was that Monte, a Cub Scout, grew up to become an Armenian militant. When I’ve attempted to answer this question, I’ve pointed out that people are different, that even as a child Monte was daring, stubborn, curious, and smart. I’ve pointed out that Monte’s character combined a high esteem for mathematics and historical accuracy with a relentless will to confront and overcome adversity.

I’ve described the role that family history, travel, and book learning played in his intellectual development. But to be honest, none of these responses have really satisfied me. I’ve never been able to come up with a satisfactory off-the-cuff response to the most frequent question people ask about my brother. So I’ve concluded that the only way to answer this question properly is to tell a complete story about Monte’s life. My Brother’s Road is a 300-page answer to the question - How did Monte become who he became?

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (1)

Write a comment