Post WWII Armenian Repatriation: The Visions & Illusions of the Station

An interview with Fresno painter Hazel-Takouhie Antaramian

After WWII and until the collapse of the Soviet Union, Armenia resembled a large waiting room in a station, in which “travellers” would come and go. Others just waited for their time to depart. They were people in search of a Homeland, oftentimes not noticing or comprehending its true nature. The constant clashes between the vision of the Promised Land and the crude Soviet system, between the fixations of a fringe region of the Russian Empire and imported (essentially Western) culture, forced the travelers to decide to return, without ever leaving the station. During a fifty year period, tens of thousands of families entered and then exited the country in such fashion.

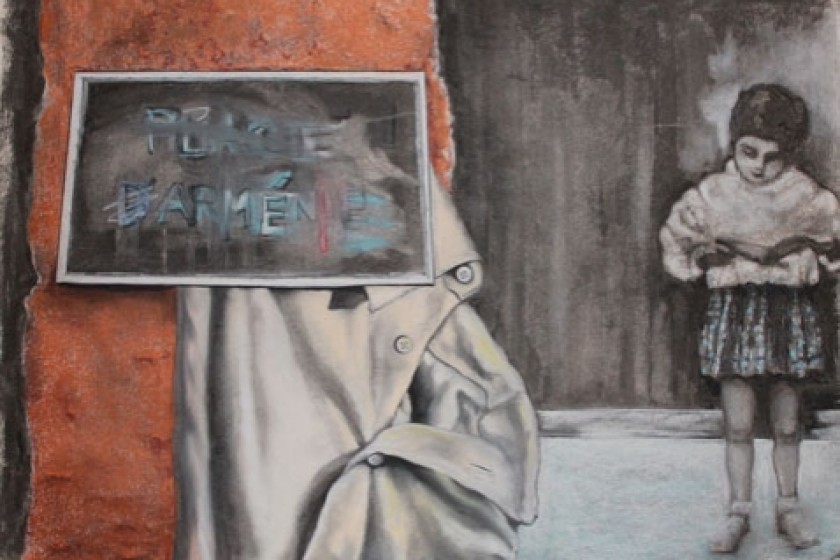

The Antaramians are one such family. The father was born in the U.S. state of Wisconsin, the mother, in the French city of Lyon, and the daughter, Hazel-Takouhie, in Yerevan, the capital of Soviet Armenia. When Hazel was just five, the Antaramian family left Armenia. The move raised a number of thoughts in the young girl’s mind. Fifty years later, these thoughts have become the basis for an art project conceived by the painter Hazel Antaramian-Hofman. The project fuses memories and oral histories, photos and documents and, of course, colors and images drawn from early childhood scenes.

On March 21, at the Fresno Armenian Museum, Hazel Antaramian-Hofman will showcase her audio-visual project «Repatriation and Deception: Post World War II Soviet Armenia». It will be made available on her website.

The topics concerning the Armenian Genocide and survival of the people is more real in the Diaspora nowadays. Why did you decide to choose the topic of repatriation?

The topics concerning the Armenian Genocide and survival of the people is more real in the Diaspora nowadays. Why did you decide to choose the topic of repatriation?

I would say that I did not choose the repatriation topic, but that the topic chose me.

It is the reason of my existence both literally and figurative. I was born in Soviet Armenia to two post-WWII repatriates, whose families came from the United States and France respectively.

My family eventually left Soviet Armenia in 1965. We were considered among the first families to leave the country. Later while living in the United States, I would hear stories about life in Armenia during the 50s and 60s without ever realizing the significance of the repatriation.

The names that I now see in archival research papers and newspaper articles were the names that I heard while growing up. When repatriate friends who were still in Armenia began leaving in the early 1970s, I would hear my family say such things as “Did you know that ‘so-and-so’ got out?”

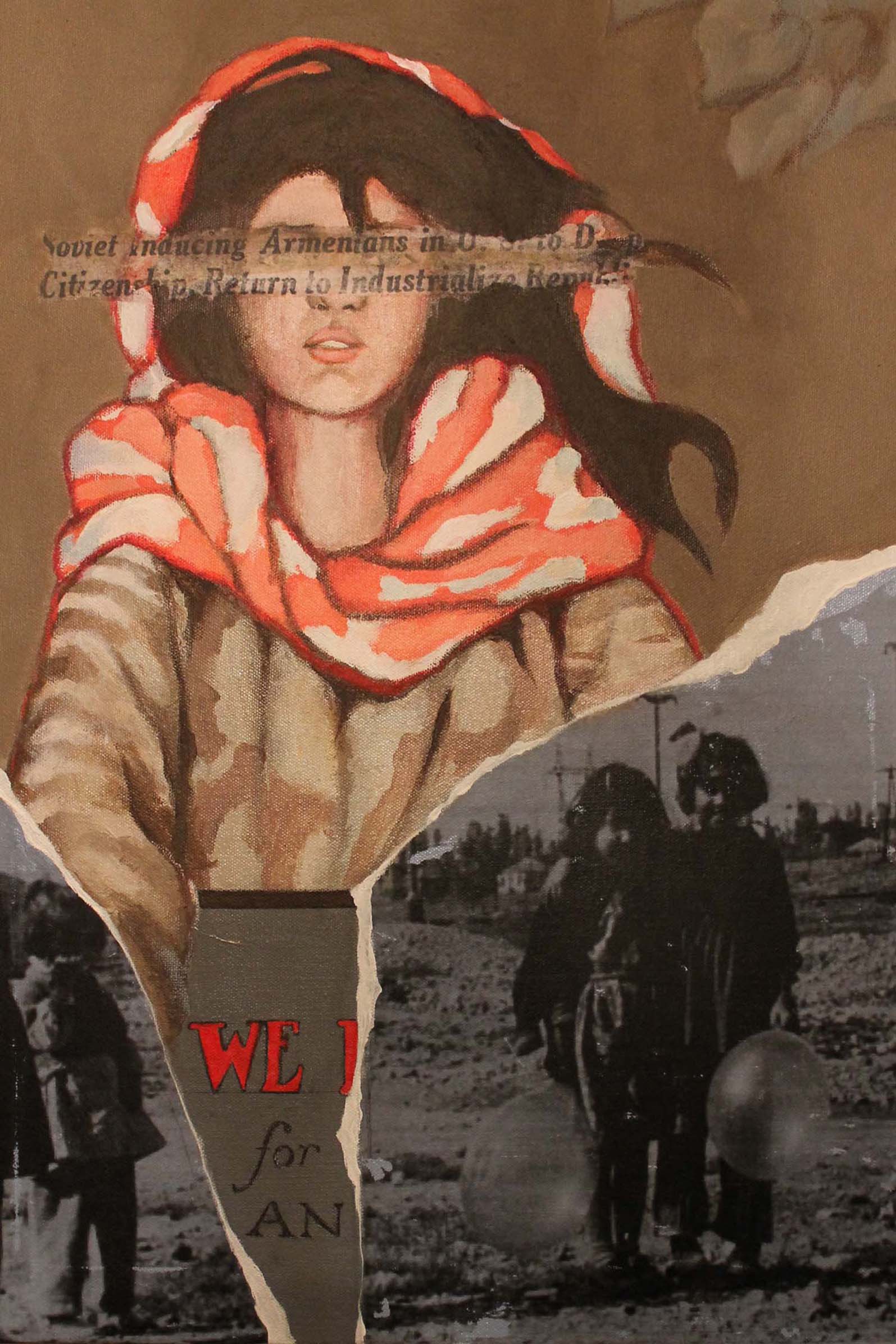

Going back to my current work on the repatriation—Armenians who “repatriated” after WWII were part of the largest campaign organized by the Soviet government and, I believe, among the most troubling. It was a history that I wanted to document. It was my history. So after having completed my graduate degree in art at Fresno State University, in December of 2011, I began to search for ways that I could manifest the sentiment I have long had for the repatriates. I am now doing this with my paintings and drawings, my writing, and my personal devotion to the repatriates for the sacrifices they made, which I strongly feel led to the advancement of Armenia.

Being an artist, how will you combine fine art and documentary research?

The inspiration for my paintings and drawings come from the stories and images of surviving repatriates. So you could say that the repatriation story is my “muse.”

My documentation process entailed casual visits with repatriates. Then when I began my website a few months ago, I realized that I needed to share the stories and images that I collected since it was an integral part of Armenia’s modern social and ethnographic history. My website is a work in progress; I hope to continue to add to it as well as to link to other sites that address this history. I consider my artwork as an interpretive and visceral response to what had happened during this time in Armenian history. Along with my love to paint and draw, I love to write. So my research and interviews became the basis for my essays on the topic.

|

|

|

In your opinion why did most of the Armenian repatriates of 1946-49 leave their countries of residence?

I found that for each family there were nuances for wanting to return during this time in history. But the overwhelming reason that masked these nuances was one of Armenian sentimentality and belonging.

For those who made the decision to go, there was a romantic notion of living within the aura of Mount Ararat, the land where their ancestors perished. It was also important for the repatriates to be living among the people who spoke their language, and understood their traditions and customs.

One of the American-Armenian repatriates who I interviewed last year told me that at the time of the repatriation she was in her early 20s, and that she did not want to leave the United States. She reluctantly attended a repatriation “propaganda” meeting in the Catskills in New York with her father.

After seeing tears in the eyes of a man who she characterized as a typical dispassionate Armenian father once the film about returning to the “fatherland” was over, she changed her mind. She did not want to further rip apart the Armenian family fabric as the genocide had done to her parents.

Such propaganda movies were commonly shown by repatriation committees in Armenian Diaspora communities. The imagery depicted in the films played upon emotions and a sense of nationalism, particularly affecting those who remembered life as Western Armenians in the Ottoman Empire.

4. The topic of demographic problems is much spoken in Armenia nowadays. Do you think it’ll be possible to arrange a new repatriation movement and what must first be done to make it happen?

I have visited Armenian twice since I left as a child in 1965 - the first time in 2006 as a tourist with my son, and the second time in 2012 as a researcher.

In 2006, I had some emotional moments as I stood in places I only remembered from family photographs. But after talking to the locals and touring Yerevan on foot, I did notice shifts in demographics.

Later in 2012, I experienced seeing more dramatic changes in the country, perhaps a continual push toward Westernization. Armenia is a beautiful country and conceivably many of its attributes could attract Armenians from the Diaspora, either as visitors or “repatriates.”

But it is highly unlikely that a massive repatriation can be organized again like the one after WWII, unless for imperiled Armenians living in the Diaspora, such as in Syria or other parts of the Middle East. Many Armenians in Europe and the United States no longer see their lives in these countries as disenfranchised.

The ease with which one can travel to the country also makes it unlikely. If they “come back,” it is a decision based on individual aspirations.

And for Armenia to attract citizens from the outside, it needs to address many of its internal problems, including government corruption and unethical business practices; health and environmental issues; and long-term economic opportunities for its people, before entertaining the idea of inviting permanent newcomers.

From an artist’s perspective, I would love to see an intensified “beautification” effort of Yerevan, and a meaningful preservation of Armenia’s natural landscape and cultural history. I hope that my work on the history of the repatriation, via my writing and artwork, initiates a dialogue about the idea of repatriation and how the government of Armenia addresses it.

Now that an apology has been issued by the Armenian government to the repatriates from the late 1940s, the Minister of the Diaspora should take steps to officially recognize the contributions made by the repatriates to Armenia—maybe an annual day of commemoration?

How many Armenians in the Republic of Armenia really comprehend the history associated with the late 40s repatriation, or the background of those Armenians who in masses dispersed to all corners of the world at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century?

Along with the recognition of the genocide, I believe we need to acknowledge those who “repatriated,” to Armenia, in particular, those who gave up their lives in the process.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (4)

Write a comment