Armenia now enjoys the dubious distinction of being a transit nation for endangered animals.

These animals, from exotic African varieties listed in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species to those native to Indonesia, are being trafficked through Armenia without difficulty.

The sale of proscribed animals is the 4th most profitable illegal business worldwide, following drug trafficking, human trafficking, and fraud. And the illegal trade of animals continues to grow yearly, and is now regarded as a major component of overall international crime.

Some of the animals brought to Armenia remain in the country. Some are used as "attractions" at various businesses, like the street hawkers of old, to pul in customers. Some wind up as pets in the homes of Armenia's rich or wannabee-rich, to impress the neighbors or to add a touch of "class".

The animal seen in the accompanying photos is the bonobo, (Pan Paniscus), formerly called the pygmy chimpanzee and less often, the dwarf or gracile chimpanzee. Native to the Congo Basin in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the species was listed as endangered on the IUCN Red List in 1996, and is threatened by habitat destruction and human population growth.

The sale and export of the animal is banned in the DRC. Despite the ban, an animal resembling the bonobo has turned up in Armenia. The animal can be seen caged in the newly opened Jambo Park located in Dzoragbyur, a town in Kotayk Province.

The “exotic park” is part of a restaurant complex that opened this past September. It’s the brainchild of Artyom Vardanyan, a businessman who relocated to Armenia, who likes to show off the rare animals in his collection.

|

| Experts in the field are worried that if present trends continue the bonobo population will decrease by 50% in three generations. |

Illegal poaching is the main culprit, along with habitat destruction. The civil wars that racked the DCR in the 1990s and the ensuing lack of adequate conservation oversight opened the door to greater poaching on an organized level.

The threats facing native stocks of bonobo grew to the point that the ICUN adopted a 2012-2022 conservation strategy for preserving the species.

The export, sale or transport of rare animals is regulated by the CITES (the 1973 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, which Armenia signed on to in 2009.

The convention stipulates that each country which obtains ant animal species is then obligated to organize trade in accordance to convention procedures and with all specified permits. Appendices to the convention include lists of the most endangered animals, and the bonobo is listed as “critically endangered” with the highest protection status and not trade of wild caught animals permitted.

In Armenia, the Ministry of Nature Protection (MNP) is tasked with seeing that the obligations of the convention are adhered to. The person directly responsible is Siranush Muradyan, Head of the Dendropark Management Division at the Ministry’s Bioresources Management Agency.

Hetq contacted the MNP, asking that it supply of with a list of animals being imported to Armenia that show up as “critically endangered” in the CITES appendices. The bonobo wasn’t on the list they sent us.

How did the bonobo show up in Armenia?

As Artyom Vardanyan boasted in a local Armenian TV show, he paid a great deal of money for the bonobo. “The animal showed up at the Bonn Zoo. Such an animal can fetch 150,000 Euros on the open market. I purchased it and paid a large sum.”

Vardanyan told Hetq that the transaction was legal and that he has the CITES permit as proof. When then asked him to produce the permit. A quick glance at the document shows the importer’s address and the country of export as Guinea. West Africa Zoo appears as the exporting organization and the document is dated May 4, 2011. When we asked Vardanyan about the sales certificate, he said that he hadn’t actually purchased the animal but had “leased” it from the importer, Artur Khachatryan. He advised us to get in touch with Khachatryan for the details.

Artur Khachatryan is the founder and sole owner of Zoo Fauna Art, a company in the animal trade. The firm buys and sells animals in an import-export network that covers Russia, the UAE, and other countries. Khachatryan has ties with all the major international players in the animal trade.

He’s purchased a large tract of land adjacent to the Erebouni Preserve-Museum just outside Yerevan and is building a zoo there. He likes to refer to himself in the third person, and says, “Mr. Khachatryan is building the biggest zoo in all of Eastern Europe.” He’s currently raising animals there and it’s where he stores imported animals for export later on. Khachatryan boasted that he could get any animal he wants with little difficulty.

“These monkeys have been legally imported. I know the CITES convention back and forth by heart. You are mistaken,” he responded, when we asked about the bonobo.

When we tried to get Khachatryan to agree to letting us take photos at the zoo and to see the documents, he balked. He said we could meet, but ruled out any video or audio taping, arguing that he didn’t see the need.

Artur Khachatryan did tell us that he imported two bonobos from Guinea in 2011. One is now on display at Jambo Park. The other died a week after reaching Armenia. Khachatryan says the animal was in poor condition when it arrived.

He claims that the bonobo wasn’t taken from the wild but was captive bred. Even if true, the MNP in Armenia is obliged not to grant preliminary permission for importation. They have to issue the import permit before the export permit and can not do so without confirming that the animal comes from a CITES approved breeding facility for the species and there is no such facility in the whole of Africa.

“Preliminary permission for an animal listed in the first appendix is withdrawn when the animal in question is taken from the wild. If you take the animal from a farm or zoo, or one born in captivity, it is automatically listed as CITES II, but is written CITES F or captive (C), an animal bred in captivity intended for a zoo,” Artur Khachatryan noted as justification.

Khachatryan’s explanation is also backed up by Siranush Muradyan who acts as the Convention’s mission representative in Armenia, noting that such animals may not be registered in their list of imported animals. There is a must to register them with a CITES Import permit and then list them in the annual trade database.

However, the code regarding the granting of permits for the import or export to and from Armenia of wild fauna and flora covered under the Convention, paint a different picture.

The Convention’s Armenian Mission isn’t aware of what animal species regulated by the Convention are entering Armenia. Nor is it interested in the fate of these animals once they arrive. The mission also doesn’t know about the permits involved when animals are taken to and from Armenia.

We still haven’t received a reply from the Convention’s Guinea Mission, asking if they know if a bonobo was ever exported to Armenia.

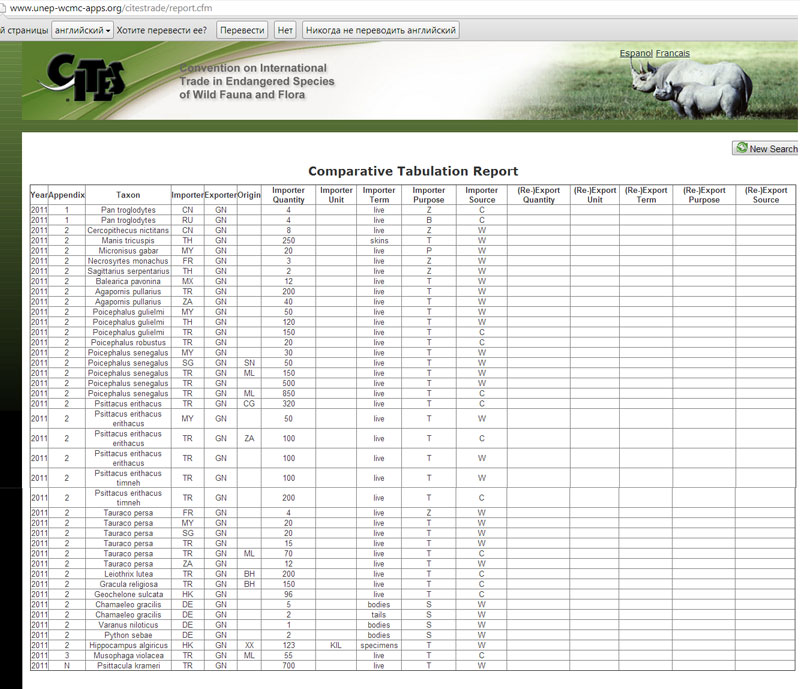

The CITES data base on the trade in endangered species of wild fauna and flora, has no information of a bonobo ever being exported from Guinea to Armenia. The chart below shows all animals exported from Guinea in 2011. There are no pan paniscus listed.

A 2013 report jointly published by the United Nations Environment Programme and UNESCO entitled Stolen Apes: The Illicit Trade in Chimpanzees, Gorillas, Bonobos and Orangutans reveals that Guinea is engaged in the granting of falsified permits.

In 2007, Guinea exported a large number of chimpanzees to China as legal, with CITES permits stating that the animals had been raised in captivity and not taken from the wild. The CITES secretariats sent a mission to Guinea and discovered that 69 chimps had been taken out of the country in 2010 alone, destined for Chinese zoos and safari parks. Investigations by non-profits and individuals reveal that 138 chimps and 10 gorillas have been exported to China in this manner - this, despite the fact that no breeding farms exist in Guinea. Investigators suspect that the animals were actually transported from the neighboring countries of Cameroon, the Ivory Coast, the DRC, Libya and others, and were all wild caught with up to 10 animals killed to secure one live baby.

Through our partners in Africa, we tried to find out if there actually is a zoo called West Africa Zoo in Guinea. According to information we’ve received, no such zoo exists. In addition, there is no such legal facility in Guinea that can breed animals.

How old is the bonobo now on exhibit in Armenia?

A staff member at the Jambo Park told a visitor last month that their Boni (that’s how they call the bonobo), is eight months old. A foreign expert (whose name we will withhold for now), more or less confirmed this, stating that the animal’s maximum age doesn’t exceed 1.5 years. The expert says that the Jambo Park bonobo is not three years old, meaning that it couldn’t have been imported to Armenia in 2011. Most probably the bonobo is another animal with no legal documentation papers.

| According to the National Statistical Service of Armenia, 286 primates were imported in 2011 and 133 in 2012 |

From 2011 to 2012, several exotic animal species were imported to Armenia – leopards, crocodiles, several types of monkeys, lions, large numbers of wild boar, a wide variety of parrots, snakes, and others. It cannot be ruled out that the Jambo Park bonobo was imported along with the other monkeys as a non-endangered specimen.

Animals exported from Armenia mostly wind up in Russia and the UAE. In 2011, 43 monkeys of various species were exported to Russia and 111 in 2012. There were no CITES animal imports to Armenia from Russia. There are animal imports from the UAE to Armenia, but they are less than those exported from Armenia to the UAE.

Chimpanzees are also endangered

|

| In the past seven years, 643 chimps, 48 bonobos, 98 gorillas and 1,019 orangutans have been captured in the wild for illegal trafficking. The number of chimps in the wild is decreasing yearly. |

Different monkey species are exhibited at Jambo Park. Artyom Vardanyan owns 75 monkeys including 4 chimps, mangabeys, mandrills, and others. There are also rare bird species, like the black parrot, on display. Chimpanzees have also been included as a vanishing species on the ICUN’s Red List since 1996.

Artyom Vardanyan claims that he also got the chimps from Artur Khachatryan and again advised us to get any details from him. Khachatryan isn’t in Armenia right now.

Hetq will follow this story to find out how these and other animals get in and out of Armenia.

(To be continued)

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (3)

Write a comment