Photographer Ara Oshagan: “I’ve always wanted to photograph average folk, not leaders”

His work has taken him to Artsakh and behind California prison walls.

American-Armenian photographer Ara Oshagan attaches his photos to the wall and stares at them for a long time. Those that lose their interest after a few weeks for the photographer are removed from the wall and replaced by new ones. A photo that Ara took in the village of Vank (NKR) in 2006 stayed on the wall for quite a while, never boring the photographer. The photo was taken next to the fountain in Vank, close to a restaurant that looks like a boat and a store. It was dark inside the store and bright outside.

His work has taken him to Artsakh and behind California prison walls.

American-Armenian photographer Ara Oshagan attaches his photos to the wall and stares at them for a long time. Those that lose their interest after a few weeks for the photographer are removed from the wall and replaced by new ones. A photo that Ara took in the village of Vank (NKR) in 2006 stayed on the wall for quite a while, never boring the photographer. The photo was taken next to the fountain in Vank, close to a restaurant that looks like a boat and a store. It was dark inside the store and bright outside.

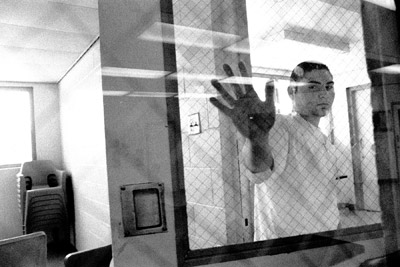

The store's glass shone like a mirror. Ara took a photo from the outside, capturing the image of a village elder on the glass. "It seems that the person is slowly coming out from behind that mirror. If you look from the left side over to the right, that elderly person gradually appears more completely in the shot," Ara said.

The main idea of the book "Father Land" sprung from this photo and from the concept of appearance. Ara says, "That photo became a central one for the idea of appearing, which is an important idea for this book, since I prepared the book with my father. I became a father during the time I worked on this book. I've had four children over the course of the ten years I've worked on the book. I started work on it with my father. He did at the end. So, not only have I become a father but I have taken over my father's place. This ten year process has thus become a process of self-realization for me at the same time."

The store's glass shone like a mirror. Ara took a photo from the outside, capturing the image of a village elder on the glass. "It seems that the person is slowly coming out from behind that mirror. If you look from the left side over to the right, that elderly person gradually appears more completely in the shot," Ara said.

The main idea of the book "Father Land" sprung from this photo and from the concept of appearance. Ara says, "That photo became a central one for the idea of appearing, which is an important idea for this book, since I prepared the book with my father. I became a father during the time I worked on this book. I've had four children over the course of the ten years I've worked on the book. I started work on it with my father. He did at the end. So, not only have I become a father but I have taken over my father's place. This ten year process has thus become a process of self-realization for me at the same time."

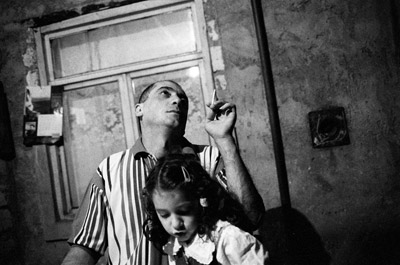

Ara first visited Karabakh with his famous father, Vahe Oshagan, in 1999. The last time Ara was in Karabakh was in 2006 to photograph the book "Father Land". "they have always received me well in Karabakh and that is the most wonderful thing. Every day people invite me top their homes to drink coffee and talk. In America, three years can go by without anyone inviting me over their house if we are not friends. Oftentimes, I would spend 1-2 hours at somebody's house, sitting and talking, without taking even one photo because , for me, the process of taking pictures is simultaneously a process of creating relations. And sometimes you have to create relationships without photography and it can turn out that you attach a very good photo to the wall. Talking is very important," Ara said.

Ara first visited Karabakh with his famous father, Vahe Oshagan, in 1999. The last time Ara was in Karabakh was in 2006 to photograph the book "Father Land". "they have always received me well in Karabakh and that is the most wonderful thing. Every day people invite me top their homes to drink coffee and talk. In America, three years can go by without anyone inviting me over their house if we are not friends. Oftentimes, I would spend 1-2 hours at somebody's house, sitting and talking, without taking even one photo because , for me, the process of taking pictures is simultaneously a process of creating relations. And sometimes you have to create relationships without photography and it can turn out that you attach a very good photo to the wall. Talking is very important," Ara said.

The photos taken in Artsakh won 3rd prize at the national "Visions 2001" competition. There are no photos of the Artsakh landscape or tourist sites in the book "Father Land"; just people. The book includes lengthy texts by the photographer's father, Vahe Oshagan, on the history, war and culture of Artsakh and impressions of the author. The book will be published this September in New York. Ara definitely wants to introduce the book to audiences in Armenia and Artsakh and organize an exhibit.

The photographer dreams of writing a novel

Ara was born in Beirut. The family relocated to America was Ara was a young child. He lives there now with his wife and four children. He says he became a photographer by accident. He wanted to be a writer like his father. Sra still dream about becoming a writer and has one or two ideas for a novel in his head. He's written short stories in English for a long time but, as he puts it, never has had the courage to tackle a novel. One day, Ara decided to include photos with his short stories and turned to his photographer friend for help. Ara, however, didn't think his friend's photos corresponded to his stories, so he started to take photos.

"I started to take more and more photos and gradually immersed myself in photography, honing my skills. Then, a day came when I realized it wasn't important whether you are a writer, a photographer, a painter or in music. What's important is what you want to convey by a certain medium. When I realized this I gave up writing and totally focused on photography," Ara recounted.

He doesn't like to shoot official events and officials. When he goes to a festival, he doesn't shoot from the stage but captures what is going on behind the scenes.

"Let's say that during my work in Karabakh I had the chance to rub shoulders with various government types. But I always, always, kept my distance from such encounters. I constantly wanted to be amongst the average, natural folk, in contact with their daily life, immersed in that life, to photography in that environment rather than take the picture of some leader. There is some role-playing that goes on in official circles; people must speak and act a certain way. When you photograph people in their homes and other natural surroundings, that aspect doesn't come into play. I feel it's easier to reach a certain degree of truth," Ara said.

Documenting testimony of Genocide survivors

Starting back in 1995, Ara Oshagan has photographed Genocide survivors residing in America. There were still some left at the time. Ara also took down their histories. He and his friends interviewed and photographed 80 Genocide survivors.

"Most lost their mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers. They were killed before their eyes. They sometimes asked why they survived and the others didn't. Their emotional world is very complex and difficult to bear not only because it took place and is not recognized, but because they witnessed it all and it's hard to live with those memories," said Ara.

The photographer has also met Genocide survivors who blame Armenians for not adequately resisting the Turks. "There is this one survivor who would say, 'How is it that we went and got massacred. My father would say there were a hundred Armenians around and just the one Turkish soldier to guard us. Why didn't you do anything.' Yes, a few people asked the question - how could it happen?"

He intends to write a book that will include photographs and stories of Genocide survivors. It will most likely be published after "Father Land"

A secret world that very few get to see

Ara Oshagan has also worked in a prison, photographing young law breakers in California.

"Working inside a prison is very interesting because it's a secretive place behind massive walls that one never sees unless you are sentenced for a crime. I had the unique opportunity to go and see how they live, even though I never committed a crime or was sentenced. It's a secret world that few get to see. It was an exceptional new thing for me."

The photos taken in Artsakh won 3rd prize at the national "Visions 2001" competition. There are no photos of the Artsakh landscape or tourist sites in the book "Father Land"; just people. The book includes lengthy texts by the photographer's father, Vahe Oshagan, on the history, war and culture of Artsakh and impressions of the author. The book will be published this September in New York. Ara definitely wants to introduce the book to audiences in Armenia and Artsakh and organize an exhibit.

The photographer dreams of writing a novel

Ara was born in Beirut. The family relocated to America was Ara was a young child. He lives there now with his wife and four children. He says he became a photographer by accident. He wanted to be a writer like his father. Sra still dream about becoming a writer and has one or two ideas for a novel in his head. He's written short stories in English for a long time but, as he puts it, never has had the courage to tackle a novel. One day, Ara decided to include photos with his short stories and turned to his photographer friend for help. Ara, however, didn't think his friend's photos corresponded to his stories, so he started to take photos.

"I started to take more and more photos and gradually immersed myself in photography, honing my skills. Then, a day came when I realized it wasn't important whether you are a writer, a photographer, a painter or in music. What's important is what you want to convey by a certain medium. When I realized this I gave up writing and totally focused on photography," Ara recounted.

He doesn't like to shoot official events and officials. When he goes to a festival, he doesn't shoot from the stage but captures what is going on behind the scenes.

"Let's say that during my work in Karabakh I had the chance to rub shoulders with various government types. But I always, always, kept my distance from such encounters. I constantly wanted to be amongst the average, natural folk, in contact with their daily life, immersed in that life, to photography in that environment rather than take the picture of some leader. There is some role-playing that goes on in official circles; people must speak and act a certain way. When you photograph people in their homes and other natural surroundings, that aspect doesn't come into play. I feel it's easier to reach a certain degree of truth," Ara said.

Documenting testimony of Genocide survivors

Starting back in 1995, Ara Oshagan has photographed Genocide survivors residing in America. There were still some left at the time. Ara also took down their histories. He and his friends interviewed and photographed 80 Genocide survivors.

"Most lost their mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers. They were killed before their eyes. They sometimes asked why they survived and the others didn't. Their emotional world is very complex and difficult to bear not only because it took place and is not recognized, but because they witnessed it all and it's hard to live with those memories," said Ara.

The photographer has also met Genocide survivors who blame Armenians for not adequately resisting the Turks. "There is this one survivor who would say, 'How is it that we went and got massacred. My father would say there were a hundred Armenians around and just the one Turkish soldier to guard us. Why didn't you do anything.' Yes, a few people asked the question - how could it happen?"

He intends to write a book that will include photographs and stories of Genocide survivors. It will most likely be published after "Father Land"

A secret world that very few get to see

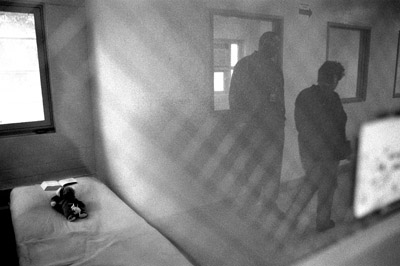

Ara Oshagan has also worked in a prison, photographing young law breakers in California.

"Working inside a prison is very interesting because it's a secretive place behind massive walls that one never sees unless you are sentenced for a crime. I had the unique opportunity to go and see how they live, even though I never committed a crime or was sentenced. It's a secret world that few get to see. It was an exceptional new thing for me."

Ara Oshagan worked 1-2 hours per day in the prison, a fairly short time to capture the psychological state of young criminals behind bars. After two years of taking photos in the prison, Ara realized that something was amiss; there was a lack of depth.

Ara Oshagan worked 1-2 hours per day in the prison, a fairly short time to capture the psychological state of young criminals behind bars. After two years of taking photos in the prison, Ara realized that something was amiss; there was a lack of depth.

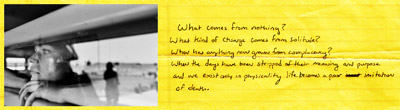

To fill the void he included a text with the photos, snippets of letters, essays and poems, written by the young inmates.

To fill the void he included a text with the photos, snippets of letters, essays and poems, written by the young inmates.

"One or two of them really wrote some good poetry. The first time I visited the prison I thought I'd be meeting up with a bunch of gangsters, tattooed tough guys, but they were a modest group of boys and girls. They were bright and curious and wanted to learn how to shoot a video. They weren't all that different from our friends," Ara said.

Besides arranging photos with text, Ara sometimes positions one photograph next to another, or sometimes three in a group. The aim is to create greater photographic possibilities to not only showcase the prison inmates but the history of the place where they live. Also, when the handwritten pieces of the inmates are included, or their photos, the stories of the inmates is told as well. This is very important to every inmate behind bars because they are dispossessed of everything; even their clothes. Ara says that this photographic project is an attempt to afford young criminals the right to be heard in a place where they have nothing that belongs to them.

Ara Oshagan is looking for a publisher for his book of photos of these young lawbreakers. On June 2, in New York, the "Moving Walls" exhibition opened. Every year, scores of photographers submit their work for inclusion, but only six win that honor. Over the years, Ara has also applied but was turned down. This year he won one of the coveted six spots with his series of "Moving Walls" prison photos.

"One or two of them really wrote some good poetry. The first time I visited the prison I thought I'd be meeting up with a bunch of gangsters, tattooed tough guys, but they were a modest group of boys and girls. They were bright and curious and wanted to learn how to shoot a video. They weren't all that different from our friends," Ara said.

Besides arranging photos with text, Ara sometimes positions one photograph next to another, or sometimes three in a group. The aim is to create greater photographic possibilities to not only showcase the prison inmates but the history of the place where they live. Also, when the handwritten pieces of the inmates are included, or their photos, the stories of the inmates is told as well. This is very important to every inmate behind bars because they are dispossessed of everything; even their clothes. Ara says that this photographic project is an attempt to afford young criminals the right to be heard in a place where they have nothing that belongs to them.

Ara Oshagan is looking for a publisher for his book of photos of these young lawbreakers. On June 2, in New York, the "Moving Walls" exhibition opened. Every year, scores of photographers submit their work for inclusion, but only six win that honor. Over the years, Ara has also applied but was turned down. This year he won one of the coveted six spots with his series of "Moving Walls" prison photos.

If you found a typo you can notify us by selecting the text area and pressing CTRL+Enter

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment