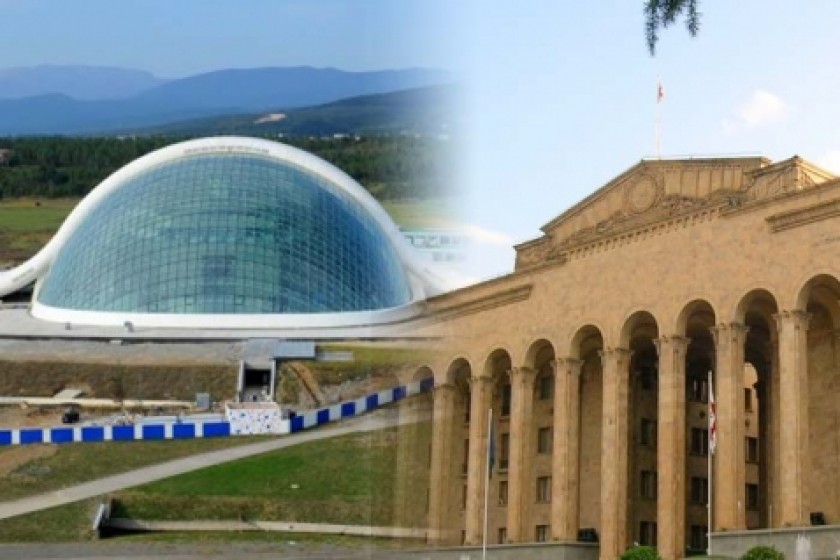

A Tale of Two Parliaments

WRITTEN BY NINO BAKRADZE

Georgian lawmakers waste millions because they can't even agree on where to meet.

The Republic of Georgia is not a rich country, so it is hard to fathom why it has spent more than US$ 250 million over the past six years to run two separate Parliament buildings in two cities 200 kilometers apart.

The entire annual budget is only about US$ 4.5 billion but things are getting worse. The recent conflict between Ukraine and Russia (two major trading partners) has stifled trade and Georgia already imports three times as much as it exports. The average monthly salary is only about US$ 445—or at least it was before the Georgian currency, the lari, lost 22 percent of its value against the dollar.

So it is all the more inexplicable that since 2009, the country has spent at least US$ 257 million to build and maintain one old Parliament and one new one. Prosecutors say US$ 7 million of that sum was stolen by a politically connected contractor who built the new one.

It's a sorry tale of political intransigence, waste and a leisurely corruption investigation that seems in no hurry to reach a conclusion. Meanwhile, Georgian taxpayers pay about $200,000 more each month than they would if they had just one parliament -- the equivalent of the salary of 450 employees.

The two-Parliament mess began when Kutaisi parliamentarian Akaki Bobokhidze proposed that Parliament move from the capital city of Tbilisi to his city, located in the center of Georgia. Then-President Mikheil Saakashvili quickly agreed, although the Soviet-era building on Tbilisi’s Rustaveli Avenue was less than 60 years old. Lawmakers amended theGeorgian constitution to confirm Kutaisi, the country’s second-largest city, as the new official location for Parliament.

The effort got off to a troubled start.

The location chosen for the new building was the site of the Soviet-era Glory Memorial, which featured a massive 46-meter concrete arch honoring 300,000 Georgians and millions of other Soviet citizens killed or missing in World War II. A huge explosion to demolish the memorial was planned for Dec. 21, Saakashvili’s 42nd birthday.

It was not a popular decision.

Many saw the memorial’s destruction as an insult to Georgia’s war dead, and opposition politicians scheduled a protest rally to coincide with the demolition. In response, the government secretly moved up the blast by two days to Dec. 19; when it went off, a mother and her eight-year-old daughter were killed by flying chunks of concrete about 100 meters from the blast site.

Nonetheless, work began on the startling new complex of buildings, with a main hall shaped like a giant glass eyeball representing Georgia’s new commitment to openness and transparency. It was constructed at a cost of US$ 240.6 million.

On May 26, 2012, lawmakers met for the first time in the new building.

Four months later, Saakashvili’s United National Movement (UNM) party lost a bitter election battle to billionaire Bidzina Ivanishvili’s Georgian Dream coalition. The winner immediately began taking steps to return Parliament to Tbilisi, one of many initiatives the Georgian Dream took to undo decisions made by Saakashvili.

But it wasn't as simple as moving back into the Tbilisi building. In the interim, the old Parliament’s main chambers were deliberately gutted, a baffling decision for which nobody will take ultimate responsibility.

Sledgehammers in Tbilisi

Nugzar Lomidze is the head of the Parliament's Broadcasting Division, responsible for all audio systems. He says he saw everything that happened in the summer of 2012.

First, government employees spent a month salvaging items such as furniture and electronics from the building. “They carried everything outside and loaded it on trucks,” says Lomidze. “There was nothing in the building. It was empty. Even the parliament chairman’s office was totally emptied.”

An itemized list obtained by OCCRP showed that materials worth US$ 1,129,570 were removed by the Ministry of Economy. In addition to furniture and office equipment, those materials included hard-to-transport items such as six elevators and two heavy iron doors. (In 2014, the Ministry returned items with a value of $1,069,810 to the building. Even the elevators were hauled back in.)

Once the rooms were stripped, a half-dozen hired day workers wielding sledgehammers set to work destroying the Parliament’s main chambers and several committee rooms. They smashed walls and ruined doorways and floors.

The demolition took two weeks to finish. Lomidze and his co-workers listened as the hammers pounded away in the main chamber and the meeting rooms. “Our office had one small window from where we could see the main session hall,” he said. “The window was covered with cardboard when these workers started to demolish the hall.

“It was not only about dismantling the equipment and furniture; they destroyed everything in the hall. You can see photos of the enormous waste piles they left behind.”

“What they couldn’t carry away, they damaged,” says Lomidze. “When they took down the ceiling lights, they cut the wires as well. They acted like the bad kids who destroy birds’ nests in a village.”

Who ordered it and why is harder to figure out.

What few documents exist don’t shed much light on the matter. An executive order from Saakashvili and Davit Janiashvili, the former Parliament Secretary General, states that the ministries of Economics and Finance should decide what to do with the furnishings, electronics and computer equipment.

But this order was issued on Sept. 26, 2012, two months after the rooms were damaged. The order says nothing about who hired the men hired to demolish the classically designed chambers and meeting rooms, which were built between 1938 and 1953 with World War II German prisoners of war among the laborers.

Two Parliament workers said they knew who must have given permission.

“The head of the (building and maintenance) department, Hamlet Skhulukhia, had to give those orders,” said one of the workers, who asked that his name not be used for fear of losing his job. “I am sure that he knew what was going on here. Without his permission, the staff cannot move anything in the main halls.

“We did not have any conversation with these workers. We just saw them coming and going from the building. When they were breaking up the ceilings, the whole building was shaking. We did not have any possibility to stop them. We just said some swear words toward Saakashvili for giving such orders.”

Skhulukhia, who still holds the same supervisory job, says he was at the new Kutaisi Parliament building for the entire two-week period, and therefore was not witness to serious damage to a building for which he was responsible.

Davit Bakradze, who was UNM Parliament chairman in 2012 and still serves in the Parliament, has for seven months refused to answer questions about why the chambers were damaged.

Meriko Kokaia is based in New York and serves as a spokesperson for Saakashvili, who fled Georgia soon after his term expired in 2013 and is wanted on criminal charges. Kokaia has promised since Feb. 24 to get an answer from Saakashvili.

So far there has been no answer.

Read more

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment