Speaking Hands: Artsakh Tackles Issue of Educating the Deaf

In the mornings when 16-year-old Oksanna and her 15-year-old younger brother Alex hurry to school, they take their turns in front of the computer and sign on to Skype.

On the other end of the connection is their sign language teacher Narine Stepanyan, who works with them on their studies every day. She said that she receives silent answers, expressed with hand gestures and by mouthing words and phrases.

Oksanna and Alex Avanesyan, who live in the village of Tchartar in Artsakh’s Martouni region, are both deaf. Their mother Inna Avanesyan said that their deafness was detected when they were 2-3 years old.

“Oksanna has about 6 percent hearing while Alex has around 7 percent,” Inna Avanesyan said. “That percentage actually decreased over time since they couldn’t get adjusted to hearing aids. They couldn’t hear anything, which is why they didn’t wear them.”

The children lived in Stepanakert for three years at Boarding School #1 where they learned in a special classroom only through the fifth grade. The family also moved to Stepanakert for two years.

“Our third child had a health problem so we had to return to Tchartar,” Inna said.

In September 2014, the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh Ministry of Education’s Assessment and Testing Center arranged distance-learning courses for deaf children in the region. In the 2014-2015 school year 11 children participated and the Ministry of Social Welfare provided computers.

Inna said they have their own comfortable way of communicating with gest ures but not sign language, which she didn’t learn. Both parents say that their children do not have problems communicating with their peers.

ures but not sign language, which she didn’t learn. Both parents say that their children do not have problems communicating with their peers.

“They aren’t different from their peers.They socialize with their friends and even watch television,” Inna said. “When they were little they would become frustrated when they couldn’t make us understand what they wanted.”

When I asked them what they wanted to do when they finish school, they both smiled and looked at Inna. Oksanna made a scissor cutting gesture with her fingers and brought her hand to her hair. She wants to become a hairdresser. Alex hasn’t yet decided but his parents say that he is dexterous and from an early age he has always figured out automobiles.

Deaf Children Need Socialization

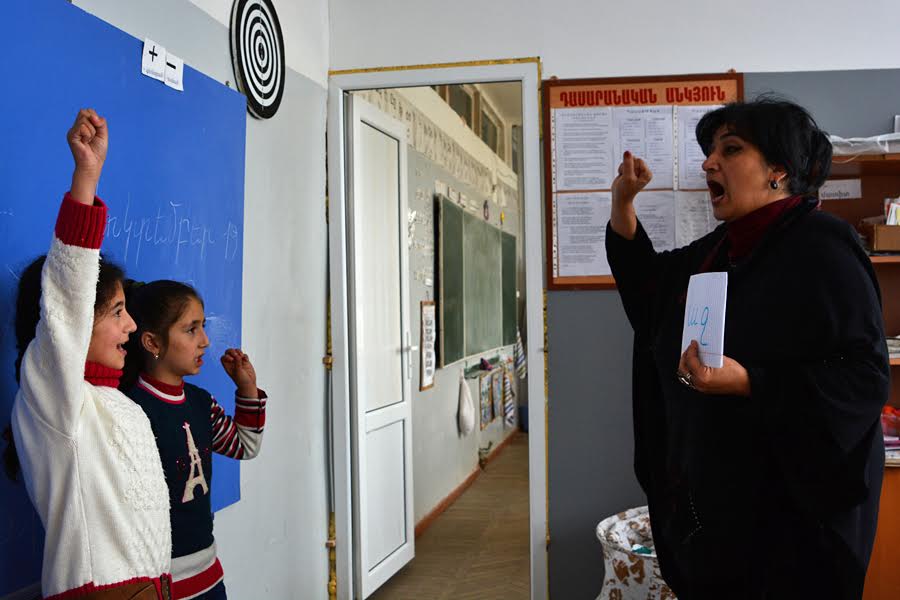

The special classroom for deaf children in Artsakh has been operating for 15 years. Since 2008 the class has been run at Stepanakert’s Middle School #9. Sign language teacher Aida Sevlikyan, who has been working with deaf children since 1998, said that there were other classes for deaf children in the city’s High School #11, where measures for physical and cultural education were better suited than in school #9.

Artur Andonyan, the principal of school #9, said that deaf students are given the opportunity to participate in various school activities.

Sign language teacher and psychologist Susanna Hayrapetyan has been working with deaf children for 15 years.

“We presently have two classrooms—middle and elementary,” Hayrapetyan said. “Both of them are mixed. The middle student classroom has four groups, which is nonsense when you consider that in the same classroom you have students from the first to the fourth grades who are not only deaf but also have other illnesses (down syndrome, cerebral palsy, etc.). A particular approach is needed for those types of children.”

Deaf students currently receive a complete school education. Experts in the Ministry of Education’s Center for Evaluation and Testing (CET) make curriculum-related decisions.

“We don’t always agree with the CET on decisions related to a particular student’s schooling,” Hayrapetyan said. “For instance, they prepared a curriculum for a deaf child guided by public education standards for a child with cerebral palsy. I don’t think that wasn’t the right thing to do, especially when it’s impossible to implement such instruction.”

She regrets that a full study has not been conducted to determine the necessary conditions for children attending school. Socialization and communication between the students are important, but they have no other means to do so outside of school.

“Not only that, one-on-one instruction was being conducted on account of the lack of contact with children, but we don’t know why those classes were cut,” Hayrapetyan said. “A young student would receive a single one-hour lesson per week while the older ones would have a 40-minute lesson.”

Middle grade subject teachers work with translators, while elementary grade teachers are trained to instruct in sign language.

Hayrapetyan believes that sending deaf students to public schools is an inhumane practice. They should instead be receiving individualized training.

The Deaf Aren’t Given Employment; Taking Responsibility an Issue

In Artsakh, placing people with disabilities for employment is a problem. Not all employers are prepared to give them jobs and provide the proper working conditions for them. Karabakh Carpet is one of those rare exceptions where today six deaf people are working. It is the only company that is currently employing the Deaf.

The head of production at Karabakh Carpet, Hasmik Mkhitaryan, admits that working with them was difficult at first but the staff now understands their gestures and interaction has become easier. Mkhitaryan now wants to hire two to three additional deaf employees and train them to become carpet weavers.

“Experience has shown that the deaf employees are more productive than the others,” she said. “Not only that, they also produce high quality work.”

Despite his young age, 20-year-old Boris Asryan, a carpet weaver from Stepanakert, is one of the most skilled workers at Karabakh Carpet, where he’s been employed for more than a year.

Boris said that he wanted to be a florist but couldn’t find work at a floral shop in Stepanakert. For now, he is satisfiedwith weaving floral designs into the carpets and making flowers out of paper at home.

“I love designing flower arrangements most of all,” he said. “But no one wants to give me a job in a floral shop.”

Center for the Deaf sign language translator Nazik Mouradyan confirmed that placing the Deaf in jobs is very difficult.

“The reality is that many employers aren’t employing the Deaf not because they don’t want to, but because they are afraid of taking responsibility,” she said. “Moreover, not everyone can understand sign language.”

The Center for the Deaf has registered a total of 196 deaf individuals in Artsakh, 43 of which are 16 and under.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment