Armenia: The Curse of Education “Reform”

By Markar Melkonian

When you hear the word “reform,” you had better grab your wallet.

Armenia has undergone thirty years of free market “reform,” and the results are there for all to see: it has benefited the top ten percent of the population, while dispossessing, depopulating, and polluting the rest of the country.

By now it is clear to all but the most doctrinaire Free Marketeers that their fairytale assumptions about “economic freedom” were worse than flawed. As it turns out, those assumptions have even conflicted with the policy directives and conditionalities of Armenia’s overlords at the World Bank, the IMF, and the Big NGO’s (the Bingo’s).

Consider education “reform.” Back in the heady days of the counter-revolution, the Free Marketeers assured us that, thanks to Armenia’s highly educated workforce, the country would thrive in the New World Order. The dream was to harness that workforce, to turn Armenia into a new Switzerland, or to make Yerevan a new Bangalore, if not the Silicon Valley of the Caucasus. Some analysts considered Armenia’s cheap, educated workforce to be one of the country’s few assets in the globalized economy: ten years ago, for example, an Armenian researcher expressed a common view among the cognoscenti: “The only comparative advantage of the Armenian economy at the entrance to the market,” he wrote, “was the higher-than-average education level of the population.” (Vazgen Arakelyan, “Privatization as a Means to Property Redistribution in Republic of Armenia and in the Russian Federation,” 2005.)

What propped up the Switzerland-and-Silicon-Valley dreams was none other than the very real educational achievements of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic. These achievements included thousands of high-quality daycare centers, safe and well-equipped primary and secondary schools, and free higher education at the State University and the Polytechnic Institute. Thanks to its first-rate system of state education, this small landlocked country had nearly universal adult literacy, an internationally acclaimed Academy of Sciences, and a developed high-tech sector that included chemical and electrical engineering, military electronics, and advanced computer technology.

It is true that personal connections and bribery played a big role when it came to access to higher education; nevertheless, the system operated roughly along meritocratic lines. If the daughter of a small farmer studied hard and made the grades, she could attend college free of charge, right through graduate school, and through post-graduate studies or medical school, too.

Many of the counter-revolutionary Moseses in Yerevan twenty-five years ago were beneficiaries of free Soviet higher education. They got their degrees in mathematics, literature, history, and philology thanks to the very Soviet system that they reviled. As soon as they achieved power, they pushed for changes that would deny high-quality education to all but a few of the next generation of Armenians.

A United Nations report (PIC3212) dated April 23, 1997 concluded that in Armenia, “Public funding for education has collapsed since independence.” This was the result of deep cuts in spending on education, down from an estimated average of US $500-600 per student to a mere US $30. The report further stated that teachers’ pay and incentives were “grossly inadequate,” amounting to only nominal salaries, equivalent to US $12 per month in 1996. Looking forward, the report noted that,

…there is a real danger that lack of access to education for those experiencing ‘transitional’ poverty could become the major factor in the emergence of structural poverty in Armenia over the medium and long term.

That prediction has been born out by developments in the years since. Puffed up with slogans about “economic freedom,” the Free Marketeers closed down schools, cut teachers’ salaries, and required fees and payment for textbooks. These policies, combined with the generalized impoverishment of the population, have put even secondary education beyond the grasp of many families.

Student absenteeism from primary and secondary schools has rapidly grown under the regime of capital, as has the dropout rate. Between 2002 and 2005 school dropout rates grew at the rate of 250% a year. (Hetq Online, Nov. 10, 2008) These developments are closely linked to the growth of child labor and the deteriorated quality of primary and secondary education in Armenia. ("Child Labour in the Republic of Armenia," M. Antonyan et. al., 2008; "School Wastage Focusing on Student Absenteeism in Armenia," Haiyan Hua, 2008)

Nine years ago, Education Minister Levon Mkrtchian summed up prospects for public education in Armenia: “If we continue to move down this path,” he said, “I am sure that we will lose the remaining quality of our education system.” (Astghik Bedevian, “New Minister Alarmed by Declining Education Standards,” RFE/RL Armenia Report, June 13, 2006.)

None of this bodes well for the prospect that Armenia’s hi-tech sector will raise the country out of poverty.

Nowadays, public education in Armenia faces yet another hurdle, namely, the de facto privatization of public schooling in Armenia. In a recent article, education researcher Hasmik Sargsyan describes how,

…more children from affluent families go to private schools and those who cannot afford the high price tag of more modern and academically rigorous alternative schools go to public schools. The latter lack the resources to be able to compete with the private schools, thus earning a reputation of being ineffective and less competent. Thus, because they cannot afford to attend the “better” schools, more and more disadvantaged Armenian children will miss the opportunity to attain better educational outcomes and better chances in life. (“Do What the West Says, Not What It Does,” The Armenian Weekly online, Nov. 17, 2015)

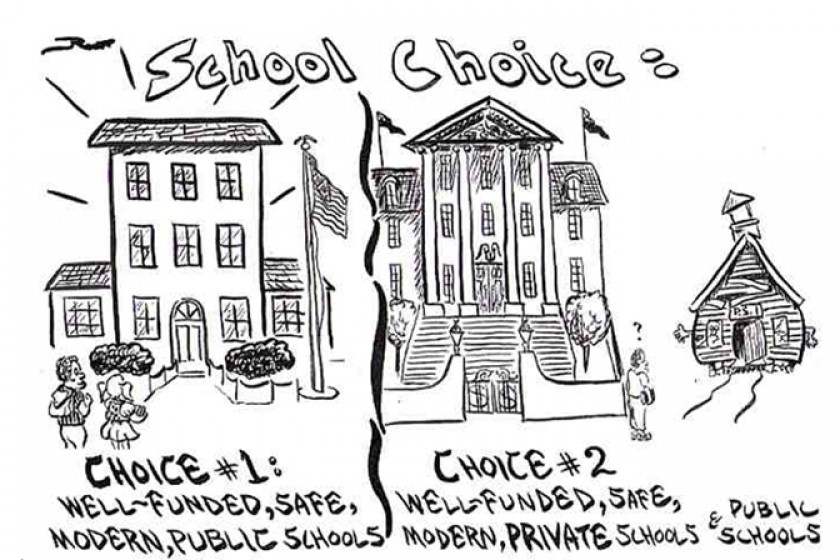

The “fashionable Western education reform tendency” of privatization is framed as enhancing “choice.” But as Sargsyan, notes, only a small minority of the wealthiest families is in a position to choose between expensive private schools and underfunded public schools. Privatization of schools, then, is yet another development that feeds inequality of opportunity in the county.

Instead of ramping up the disastrous Free Market priorities of the past, Ms. Sargsyan suggests that,

Armenia should build a strong public school system with equitable educational policies where the state, the teachers, and the schools work together collaboratively to ensure that all children have equal opportunities to receive high-quality education, regardless of their background.

Such an alternative approach, she says, has a record of success in Finland and elsewhere. One may compare this modest record of success to the dramatic record of failure for the Free Market model of education.

Let us remind ourselves that the demand for public education is, historically, a communist demand. In Chapter II of the Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels listed “free education for all children in public schools,” in addition to abolition of child labor, as one of ten sweeping measures that victorious workers should undertake when they have wrested the monopoly of political power from the hands of capitalist rulers. By contrast, Milton Friedman, the prophet of the Free Market, devoted a chapter in his bestselling book Capitalism and Freedom (1962) to “The Role of Government in Education.” Friedman opposed public provision of education, and even criticized public funding of schools. The more successful the anti-communists have been, the more thoroughly they have pushed for dismantling public education.

Capitalist rule in the Third Republic has reversed seventy years of educational achievement in Soviet Armenia. These days it seems there is not enough money to heat elementary school classrooms during Armenia’s winters. But when it comes to Free Market indoctrination, the money is there. Thanks to foreign-funded “economics textbooks,” widespread bribery of underpaid teachers, and the efforts of organizations like Junior Achievement, our capitalist rulers have been pumping Free Market propaganda into the heads of Armenia’s children the way their beneficiaries at Vallex Group have been dumping tailings runoff into the Shnogh River.

But class struggle has a way of teaching lessons that even the best-funded propaganda cannot refute. We have begun to hear voices of protest against capitalist rule. Until our compatriots can muster an organized opposition, though, the “reform” will continue apace.

Markar Melkonian is a philosophy instructor and an author. His books include Richard Rorty’s Politics: Liberalism at the End of the American Century (1999), Marxism: A Post-Cold War Primer (Westview Press, 1996), and My Brother’s Road (2005).

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (1)

Write a comment