Hadjin – Armenian Trades & Crafts During Ottoman Times

By Varty Keshishian

In Hadjin as in other Armenian populated areas, home-based trades were widely practiced from ancient times; some surviving until recent times. These trades were the primary way people made a living.

Hadjin had an Armenian population of some 20,000 and was known as an Armenian town. Local trades were mainly based on the traditions handed down by Armenian trades people. Naturally, the greater or lesser development of this or that trade was based on the natural resources of a town, the lifestyle of the of the people, and their customs.

Some trades, in the passage of time, were more widely practiced, assisting production growth and the economic prosperity of the people. If trades and craftsmanship previously developed within the confines of the home, mostly to satisfy the needs of the family, some trades broke free of these confines starting in the mid-19th century, and developed in trade shops and stores, competing with so-called market trades.

While true that trades in Hadjin had reached a certain level of development, nevertheless, taking a look at the entire picture, we can say that in comparison to other Armenian centers, trades in Hadjin didn’t shine as bright in terms of its opulence or variety. The development of this or that trade, to whatever degree, is directly related to local demand and consumer data. Thus, we can say while Hadjin was a center of craftsmanship, trades in general were a means of work or livelihood, and never a manifestation of life or lifestyle. To verify this, one need only count the number of traditional trades plied in the town – ceramics, weaving, felt making, sock making, woodworking, leather-makers, etc.

In fact, until the mid-19th century, trades in Hadjin remained within the scope of satisfying the daily needs of the people. One of the main reasons for this was the out of the way location of Hadjin. It was far removed from major trade routes. It also suffered from a scarcity of raw materials and production resources. Thus, it had little potential for real development. Starting in the 1870s and 1880s, certain developments, especially in the trade and industrial sectors, were observed in Hadjin as in the rest of the territory. A number of production enterprises were founded and traditional trades were given a boost – leather-making and woodworking, handicrafts and weaving.

Here, I will present those trade stores that employed the most people and had the most impact on Hadjin’s economy.

Tanning

One of the oldest and most developed of all the trades in Hadjin was tanning (leather-making). [1] An abundance of raw material, coupled with local demand, spurred the development of this trade, but the ancient Armenian tradition of leather-making was a larger factor. It ensured a product of higher quality and profitability.

The Tagharanots (from the Armenian taghar (earthen vessel), in which animal hides were washed) was located on the eastern side of the town along the banks of the Krded River. This trade appears to have been the best organized. The entire tagharanots was made up of 25-30 smaller trade huts and earthen vessels, where the hides, after shearing, cleaning and currying, were turned into leather for a variety of applications. [2] The soft and delicate leather was used to make women’s shoes, boots, slippers and galoshes. The rough leather was used for men’s footwear (shoes, boots), for saddles and bridles, and to produce leather parts for horse riding and household items. After meeting local demand, Hadjin leather-makers sent some of the excess to adjacent towns.

From ancient times, all artisans were members of one esnaf (Turkish for guild/corporation) governed by a higher authority. The esnaf sponsored all the tradespeople. Looking at some information about this body, I can say it was a very well organized independent association that united all master leather-makers, their assistants and students.

As everywhere, this Hadjin trade guild had its own charter, treasury and management body headed by the esnafpashi (the senior master elected by his artisan colleagues), and the guild director. [3] Garabed master Devirian and Krikor master Kesberdjikian served as guild directors. This body oversaw the rules and regulations of trade shops and settled disputes. It also assisted artisans suffering economically or those in trouble. [4]

In the early 1900s, a group of young Hadjin Armenians left for Adana to learn new skills and methods to improve leather-making back home. Upon returning to Hadjin they immediately set to work but the Genocide put an end to their plans. The town was emptied of Armenians and this trade, along with many others, came to a halt. [5]

Weaving

Another old and well represented trade of Hadjin was the making of linen/cloth. This trade too, however, was home-based to meet the needs of families until the late 19th century. Clothing and other fabrics were usually made at home. Almost all homes had a spinning wheel in front of which women would sit cross-legged and weave fabric. They would mostly use wool, cotton or sheep hair for weaving. [6]

Another trade was the making manisa of a striped fabric from cotton. The name derives from the city of Manisa (Magnesia) in Asia Minor which was famous for this trade.Manisa cotton cloth was widely used in many Armenian populated towns. It was also known as aladja. The development and spread of this trade in Hadjin is linked to the Manisadjian family. (Thus the surname) It is said that much earlier, perhaps in the mid-19th century, Nazaret agha Manisadjian started a small production unit in his house. Bringing the wooden frame of the looms (dezgeah) and thread from Marash and Adana, he began to produce manisa fabric. The cloth from this shop was highly in demand in the local market. [7]

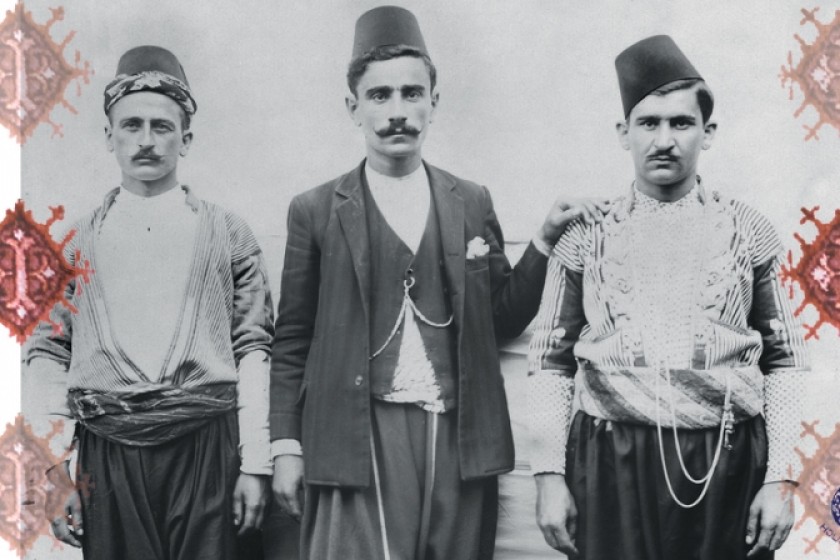

As in other Asia Minor towns, manisa was widely used in making clothing and was an obligatory part of Hadjin traditional attire of the day both for men and women. Theantari, (a robe opening in front, of silk or figured calico, reaching a little below the knee and fastened round the waist by a sash passing twice round the body) was an essential part of the traditional dress for men, was made from black or red manisa. Women wore undergarments from multi-colored manisa.

Other families also worked at the trade in Hadjin, but the scarcity of raw material and unfavorable conditions for its sale and export limited further growth of the trade.

Manisa Workshop

Immediately after the Hamidian massacres of 1895, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (an American Protestant missionary organization) sent missionary John Martin to Hadjin to support local Armenians. Through the auspices of the consulate of Great Britain in Adana, Martin reached out to British benevolent organizations and with the financial assistance they sent he contracted the construction of two huge buildings on a huge tract of land he purchased in the eastern section of Hadjin. The building on the lower stretch was allocated for the production of manisa, and a portion of the upper building was used for furniture and carpet making.

Interestingly, after researching the possibilities for the production of manisa, he opens a workshop – Manisakhan. He invites master tradesmen from Marash to put the shop on a solid footing and in a short time the business takes off. [8] (One of the tradesmen mentioned is Asdour Marashlian). He turns over running of the furniture making unit to Toros Saghdansaghian.

In his memoir, Martin refers to interesting details about these workshops, also mentioning that products from these workshops were sent in packages to the United States and to England [9].

Salwar Making

The salwar is a pair of loose, pleated trousers, made of cotton or wool. After spinning the wool and dying the yarn black, they would weave the salwar model and later cut out and sew the salwar. Traditionally, they would wear the salwar with a thick woven belt; the belt would be tied around the waist and would have wide plaits. There was great demand for the salwar in the market because it was part of one's daily attire. There were salwar weaving masters in Hadjin, who besides selling their products in Hadjin and in neighboring villages, would also send them to Marash, Kilis, Ayntab, Aleppo, Alexandrette (Iskenderun, present-day Hatay) and Adana, where they would be sold in the cities' markets. As such, we can conclude that salwar-making held an important place in Hadjin's trades.

The Munushian brothers, Makhian, Ashrian, Ushukian, Eolmkesekian, Belian, Mangurian and Gharibian etc [10] masters were famous in the trade.

Socks, Gloves, Sheets

The trades of making socks, gloves, sheets, and sewing a variety of fabric, developed alongside pants making. Those making pants were mostly women who spun the wool and sewed various items, thus meeting the needs of their families and sending large quantities to outside markets for sale. [11]

It is said that even in more recent times, when clothes sewn by hand slowly gave way to machine-made items, the men folk of Hadjin still preferred to wear woolen socks spun by their mothers and sisters.

Wool socks handmade in Hadjin were quite popular in neighboring towns with large numbers of Armenians, and large quantities were sent to outside markets. Sock making was one of the primary activities of Hadjin women. They would pass the time, especially during long winter nights, knitting socks and gloves. In addition to those working at home, there were also small ateliers in homes where young women and girls worked. [12]

Needlework

Of interest is that Hadjin never had its unique needlework decoration style that is to be found in other Armenian centers and towns.

However, like weaving, spinning, cotton cloth manufacture and other traditional trades, needlework took off, on the one hand, due to the difficult living conditions in Hadjin and, on the other, due to outside influences. With the passage of time, under the impact of that being manufactured in adjacent towns (Marash, Ayntab), Hadjin also started to make a variety of Armenian needlework and lace making items, even surpassing that being made by the original masters.

After the 1895 Hamidian massacres, missionaries arriving in Hadjin from the West spurred Armenian needlework, sending local and items produced elsewhere throughout the world and selling it in European and American markets.

One of the first initiatives to spur needlework in Hadjin was the artisan shop of Garabed Keshishian. It is said that when Keshishian worked as a teacher at Ayntab Central College he familiarized himself with the benefits of the flourishing trade of zarifeh needlework and decided to bring the bring it to Hadjin. In 1909 Keshishian invited a skilled teacher from Ayntab and opened an artisan shop in the large house of his father Hagop.

In a short while, a large number of young women and girls were learning various other Armenian styles of needlework from master teachers and learning the secrets of the trade. Obtaining the needed thread and equipment, Keshishian was able to expand the business. It’s recounted that the number of people working there sometimes surpassed 400. [13]

Hundreds of Armenian women learnt needlework in the handful of artisan shops that opened in Hadjin. Many of these women, after being exiled, were able to provide for the families in their new residences due to this trade. [14]

Read more in Houshamadyan

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (3)

Write a comment