Unregulated Animal Trafficking: How Endangered Animals Make it to Armenia and Beyond

Hrant Galstyan (Hetq.am - Armenia), Dmitro Korol (The Insider - Ukraine)

In late March, Artyom Vardanyan, a Dutch citizen and owner of Jambo Exotic Park just outside Yerevan, was arrested in Tanzania for attempting to illegally ship 61 monkeys to Armenia.

A few days later, Vardanyan declared that Artur Khachatryan, a businessman in Armenia, had purchased the animals 6-7 months earlier, with the proper documents, and that he was merely facilitating the shipment. Prior to this, Tanzanian Minister of Natural Resources and Tourism Jumanne Maghembe stated that the 61 monkeys had been captured in the span of two days and that an additional 450 had been captured in the wild in the next few days. Minister sacked the official who issued the export permits. Artyom Vardanyan then urged Khachatryan to verify that the animals were his. Khachatryan did so. The case continues to be investigated in Tanzania.

In 2013, a great ape called bonobo (Pan paniscus), listed as endangered in the International Red Book, was on display at the Jambo Exotic Park restaurant complex owned by Vardanyan. He told Hetq that the endangered ape and other chimpanzees at the park had been purchased from Artur Khachatryan who, in turn, claimed that the bonobo on display, and another one, had been shipped to Armenia from Guinea. These animals are not to be found registered in any official Armenian import list. They were brought in surreptitiously, and did not pass through customs.

Artur Khachatryan told Hetq that the second bonobo died 6-7 days after being shipped to Armenia. The one on display at Jambo died in late 2014 according to Vardanyan.

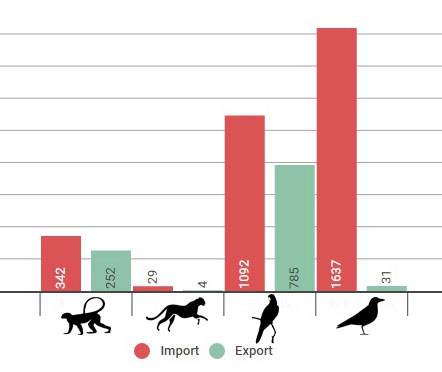

These aren’t the only animals being shipped to Armenia through illegal channels. Our investigations regarding the animal trade after 2010 show that mostly primates, wild cats, parrots and numerous other species of birds, mainly from Africa and the Arab states, are shipped to Armenia and that just a fraction show up in the official registries when exported to a third country.

The illegal trade in animals comes in third, after drug and arms trafficking, in terms of international scope. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), is an international agreement between governments to endure that international trade in specimens of wild animals and plants does not threaten their survival. Armenia joined the Convention in 2009. Currently, the Convention is the law in 182 countries.

The Convention has three appendices - lists of species afforded different levels or types of protection from over-exploitation. Attention is particularly paid to the first two.

Appendix I lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. They are threatened with extinction and CITES prohibits international trade in specimens of these species except when the purpose of the import is not commercial, for instance for scientific research. In these exceptional cases, trade may take place provided it is authorized by the granting of both an import permit and an export permit (or re-export certificate).

Appendix II lists species that are not necessarily now threatened with extinction but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. In contrast to animals included in Appendix I, no import permit is necessary for these species under CITES. More than 98% of the animal trade in endangered species consists of animals listed in this appendix.

In the years after joining CITES, a much larger batch of animals listed in the above two appendices was imported to Armenia than had been registered by the domestic management authority. For Armenia this authority is the Bio-Resources Management Agency of Armenia’s Ministry of Nature Protection.

(CITES works by subjecting international trade in specimens of selected species to certain controls. All import, export, re-export and introduction from the sea of species covered by the Convention has to be authorized through a licensing system. Each Party to the Convention must designate one or more Management Authorities in charge of administering that licensing system.)

Figures provided Hetq by Armenia’s customs service and the CITES Trade Database show that from 2010-2015 at least three times more animals were imported to Armenia than had been exported with documentation for re/export (these permissions are given by the Ministry). So, this begs the question, where did they all go?

In addition to primates, wild cats, parrots and other birds, turtles, foxes, kangaroos, bears, dolphins, porpoises and martens and even a zebra were imported to and exported from Armenia, according to Information supplied by the country’s ministry of agriculture, but their numbers were few. We should note that importation numbers are greater than shown in the diagram given that the numbers of many animals aren’t specified in the list provided by the customs service. In addition, while customs service documents show the trader picture until 2013, and the CITES Trade Database covers up till 2014, the export documents also reflect trade in 2015.

98% of the animal species of the families shown in the diagram were imported from the United Arab Emirates and 93% were exported to Russia. Moreover, in only 25% of the animals with official re-export permits is the UAE listed as the place of origin or former exporting country.

Import permits for animals listed in Appendix I of The Convention have only been issued when the animals were shipped to zoos (Z code). Meanwhile, animals from the same appendix (chimps, bonobos, diana monkeys, cheetahs, parrots, and others) have been imported into Armenia without permits. The UAE, for example, informed the CITES that since 2010 it has exported yellow-naped parrots, scarlet macaws, Salmon-crested (or Moluccan) cockatoo, jaguars, panthers and various hawk species to Armenia. During the same period, Armenia officially declared no imports from the UAE. The names of most of these animals never showed up later on in export licenses.

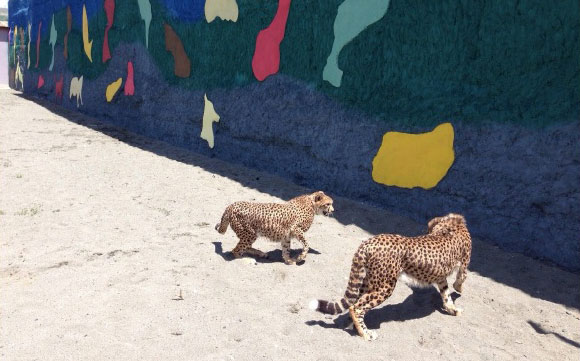

According to the CITES website, Armenia has imported 10 cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) from the UAE since 2010. The website notes that two cheetahs imported in 2011 were destined to zoos in Armenia under the “Z” code. In response to a Hetq inquiry, Yerevan Zoo Director Ruben Khachatryan stated that, “Based on data culled from documents of the past twenty years, the zoo hasn’t had any cheetahs in its collection.”

To date, only two cheetahs have been exported from Armenia with CITES permits. They were shipped from Bahrain in 2015. The fate of the ten cheetahs imported from the UAE remains unknown. They are either still in Armenia or, most probably, have been illegally exported.

Regarding the two cheetahs shipped to Armenia from Bahrain, we should note that Saudi Arabia is specified as the country of origin. According to the CITES permit provided by Armenia’s Ministry of Nature Protection, the animals weren’t captured in the wild but were raised in captivity. However, there are no captive breeding operations registered by the Convention’s regulatory body in Saudi Arabia. The only such facility is located in South Africa.

Saudi Arabia serves as a transit country. Cheetahs are shipped from Africa to Yemen, and from there to the UAE via Saudi Arabia. In addition, cheetahs are prized as exotic pets in many Gulf states. On the black market, cheetahs can fetch up to US$10,000. They are shipped to Arabian Peninsula countries from eastern Africa, a region where the most cases of illegal cheetah trafficking have been reported. Only one in six cheetahs make the journey alive. Experts note that even if the smuggled animals are later found, it’s too late to reintroduce them into the wild. They have already lost their survival skills.

The likelihood that the Saudi Arabia-Bahrain-Armenia connection may be the next illegal animal trafficking route is evidenced by the fact that according to the CITES Trade Database no export of cheetahs from Saudi Arabia to Bahrain has been registered since 1975. In July 2015, Zoo Fauna Art shipped the two cheetahs to the Crimea.

According to documents, the animals were shipped to the Donbas health resort located in the town of Yalta (Crimea). The РБК website states that in 2012 the health resort, along with the Yalta-Institute hotel complex, was purchased by Alexander Koulikov, owner of the Marins Group company and the producer of the film Vey.

It is not clear as to why Koulikov needed the animals since there is no zoo at either the health resort or the hotel to house the animals.

The only person in Crimea able to keep the cheetahs is businessman Oleg Zubkov, owner of the Skazka Zoo in the same town, and the Taiga Safari Park in the Crimea. We were not able to get any information from Zubkov. He had disagreements with Crimean authorities at the end of 2014. They intensified to the point that one year later the businessman closed the two parks. Zubkov became an “enemy to the nation after the incident and due to several interview he gave to Ukrainian new outlets.

Zoo Fauna Art

The company Zoo Fauna Art was founded in 2009 and is registered at 148 Gurgen Mahari Street in Yerevan where, in the proximity of the Erebuni Preserve-Museum, Khachatryan is preparing to build a zoo and breeding facility.

Khachatryan’s business partner is Gurgen Dumanyan, Armenia’s First Deputy Minister-Chief of Government Staff. Dumanyan, the eldest son of former Armenian health minister Derenig Dumanyan, is a 10% owner of Fauna Zoo-Breeding Facility Ltd., which the two founded in 2005. Artur Khachatryan owns 70%. Gurgen Dumanyan also has interests in other businesses.

In addition to the above-mentioned bonobos, Zoo Fauna Art has also imported 66 monkeys of various species to Armenia using false papers. A criminal smuggling case was launched against Artur Khachatryan, the director of this company, in Armenia after a series of Hetq articles focused in on the company’s dealings. Interpol placed Khachatryan on its want list after a request by the authorities of the Democratic Republic of the Congo charging the businessman with international commerce in fully protected species. The case has been dragging on in the investigative department of Armenia’s State Revenue Committee for two years. In response to a Hetq query, Ara Fidanyan, who heads Armenia’s Interpol National Central Bureau, said that Artur Khachatryan was arrested in Dubai in October 2014 but was released four months later since the Congo authorities were late in filing extradition papers. Congolese law enforcement agencies, via Interpol, petitioned their colleagues in Armenia to arrest Khachatryan. Interpol’s Armenian bureau says that Khachatryan was arrested in Armenia on February 6, 2015 but wasn’t jailed. He was released three days later.

Zoo Fauna Art is engaged in animal commerce. From 2010-2015, this company was given re-export licenses for 17 of the 20 Amazon (yellow-headed) parrots exported from Armenia. The Amazona oratrix (yellow-headed parrot) is listed as ‘endangered’ and the Amazona auropalliata (yellow-naped parrot) is listed as ‘vulnerable’ in the ICUN Red List of threatened Species. Zoo Fauna Art has exported five such birds from Armenia. However, a comparison of data from Armenia’s customs service and the CITES shows that at least 13 were imported to Armenia. All these threatened animals were brought to Armenia without import permits, a violation of CITES, and it is hard to say where these animals that haven’t received export permits are today. The fate of the Amazona parrots listed in the second appendix of CITES, the real number of which have been imported is four times the number of those issued export permits (60 to 15), remains unclear.

Artur Khachatryan is still being sought by law enforcement. This, however, hasn’t stopped him from trading in rare animals. Armenian Minister of Nature Protection Aramayis Grigoryan told Hetq that he isn’t interested in Khachatryan. Grigoryan argues that if official documents are presented, he and the ministry must issue permits, even if the animals are listed in the Red Book or not.

“I have no information as to why he is being sought and what crimes he’s committed overseas. We should have received official documents stating that those animals didn’t arrive through legal channels. We would have understood if it was legal or not. The documents presented show it was legal and we have no cause to close the route of that man. Can’t that man take us to court if we did?” said the minister.

In the summer of 2015, Artur Khachatryan exported parrots, turtles, cheetahs and 90 monkeys to Russia. Edward Khachatourian, a resident of Russia who sells exotic animals, was the importer.

Animals in Russia

In April 2015, Russia’s Chumakov Institute of Poliomyelitis and Virus Encephalitis declared an open competition to purchase laboratory animals to test the efficacy of immuno-biological substances. The value of the tender was 80,948,250 rubles to purchase 189 monkeys. The demand was for 159 African green monkeys (aged 2-4 years; 1.5-3.5 kilos), and 30 long-tailed macaques (aged 2-3 years; 1.5-3 kilos).

On May 5, the institute reported that it had received only one application and that a contract had been drawn up. The applicant was Edward Khachatourian. According to the contract, he was supposed to supply the animals not later than 200 days after the contract was signed.

On June 25, Armenia’s Ministry of Nature Protection issued Zoo Fauna Art re-export permits for 30 Grivet monkeys that came from Mali. In August, the company received re-export papers for another 60 monkeys; this time Vervets from Tanzania. Zoo Fauna Art shipped all 90 monkeys, captured in the wild, to Edward Khachatourian.

|

| Edward Khachatourian |

According to Russia’s Unified State Register of Individual Entrepreneurs, Edward Khachatourian is engaged in farming. The main sector is the growing of cultured plants. Other sectors include meat, diary, beverage and animal feed production, growing fruits and vegetables, forestry, fishing and fish farming, wild game hunting and breeding, and related services.

Edward Khachatourian is also the sole shareholder in the Monkey Planet Ltd. This company is well diversified, owning botanical gardens and zoos and selling cigarettes and books retail. Khachatourian registered the company in 2015, a few days after he and a few others “took over” more than half of the Exotic Park zoo just outside Moscow. He then built his Monkey Planet on the site. The case is now in the courts.

One of Khachatourian’s partners in Russia, who wished to remain anonymous, verified that they supplied the Chumakov Institute with the monkeys shipped from Armenia in the summer of 2015.

Chlorocebus species, including Grivets and Vervets, are widely used for research in immunology and infectious diseases, and their cell lines are still used today to produce polio and smallpox vaccines. Some reports claim that it is necessary to inoculate at least ten monkeys for every experiment and that another four are needed in the same cage to see if they’ve picked up the virus.

Parrots traveling through Armenia

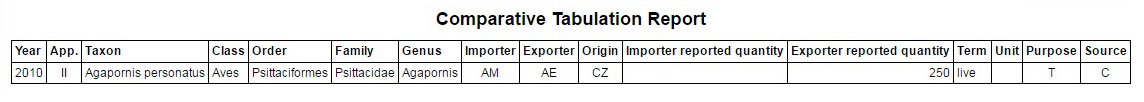

Large numbers of parrots are shipped to Armenia from the UAE. Armenia’s customs service counted 1,092 parrots brought to Armenia between 2010-2013. In many other cases involving imported parrots, only the species has been noted and not the quantity. Let’s note the following example to show just how large this number can be. According to Armenian customs service data, a batch of Czech origin Agapornis personatus (yellow-collared parrots) was imported to Armenia from the UAE. How many birds were in the shipment is not specified. However, the exporter reported to CITES that the number was 250.

As of 2010, according to the CITES Trade Database, some 1,756 African grey parrots listed as vulnerable were imported by Armenia (the Database doesn’t include 2015 trade figures). Exporters of 500 of the birds confirmed that they were captured in the wild (source code “W”). 217 of the parrots originating in South Africa were imported for the Yerevan Zoo, according to the same data, from the UAE. Zoo officials state that they did not import any grey parrots from the UAE during the years in question. During that period, export/re-export licenses were issued for 393 grey parrots. We see no future movement for 80% of the imported grey parrots.

The second largest batch of grey parrots was shipped to Armenia from the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2011. We know what later happened to 100 of the 350 imported birds from two 2013 re-export permits allowing them to be shipped to Russia. The fate of the other parrots is unknown. The price of one of these grey parrots on the Armenian page of a social website ranged from $600-$1,000.

At the 66th meeting of the CITES Standing Committee, held in Geneva on January 11, 2016, a recommendation for all Parties to suspend commercial trade in grey parrots from the DRC was presented. The DRC, among all CITES member states, has the largest number of exported grey parrots taken from the wild. In the past five years, some 45,000 grey parrots capture in the wild in DRC have been exported. The Standing Committee noted that the DRC has exceeded the annual export quota for grey parrots for various consecutive years and coupled with the fact that 50% or more of the parrots die in domestic transport before being exported, the trade ban was put up for discussion.

Efforts are underway to encourage the trade of animals bred in captivity, rather than those captured in the wild. If animals listed in the CITES Appendix I, cheetahs for example, are bred in captivity they are regarded as Appendix II animals (according to Article 7, Point 4 of CITES), and are subject to less trade restrictions. Capturing animals in the wild (noted in permits by the code “W”), and exporting for commercial aims (code “T”), are the two prime factors threatening animal populations. The Bio-Resources Management Agency in Armenia’s Ministry of Nature Protection (tasked with coordinating CITES activities in Armenia) should be on the look-out and actively working to hinder all such activities under its jurisdiction.

In addition to the above 350 grey parrots, the 600 Senegal parrots (Poicephalus senegalus) from Mali that were shipped to Armenia in 2010 and 2011 were also captured in the wild for commercial purposes. One quarter of the Senegal parrots were then shipped to Russia with a few export permits.

400 of these 600 Senegal parrots were shipped to Armenia in 2011. What is lacking in the export documents is the name of the source country; i.e. where the birds were originally imported from. Documents provided by Armenia’s customs service show they were brought from the UAE; just like all the parrots listed in the documents. The statistics show that two other species of parrots were shipped to Armenia on the same day with the Senegal parrots - 100 rose-ringed parakeets (Psittacula krameri) and 150 red-billed firefinches (Lagonosticta senegala). There is no other record regarding the transportation of the birds. Such is the manner in which most birds are brought into Armenia – their names only exist in customs documents.

There are hundreds of animals imported to Armenia and only a tiny portion are ever officially registered. The rest pass through under the radar. Of the 100 red-and-green macaws (Ara chloropterus) and the 100 blue-and-yellow macaws (Ara ararauna) captured in the wild and shipped to Armenia in 2010, only 7 have been officially exported to date. Who can say what has happened to the rest?

Those critical of CITES argue that capturing exotic animals in the wild and then posing them as “bred in captivity” when it comes time to trade them, can be a factor encouraging poaching. The CITES Standing Committee agreed stating that, “Declaring specimens as captive bred or artificially propagated has also been used to launder animals and plants illegally sourced from the wild.”

Another alarming tendency is to circumvent export restrictions for unregistered animals by claiming that they are destined for zoos (code “Z”). As noted above, two cheetahs and 217 grey parrots registered as allegedly destined to the Yerevan Zoo never made it. In addition, according to the CITRS Database, 6 blue monkeys (Ceropithecus mitis) and 6 grivet monkeys were imported from Tanzania for the Yerevan Zoo, as well as 18 blue-and-yellow macaws and 16 red-and-green macaws from the UAE.

The Yerevan Zoo, however, received no monkeys from Tanzania nor macaws from the UAE.

Armenia’s Ministry of Nature Protection says that the “Z” code is used for all zoos in Armenia. But in permits supplied by the ministry the code is only used in papers dealing with the Yerevan Zoo.

Main exporters

Most animals shipped from Armenia wind up in Russia. In addition to Artur Khachatryan, two other individuals are engaged in the business – Armen Khachatryan and Armen Kazaryan. Their names appear in most of the export licenses. Moreover, the names are registered in violation of CITES regulations. The agency issuing the permit has registered the same name and address for both the importer and exporter. Only the name of the country has been changed. It would appear that the true identity of the importer or exporter, or both, had to be concealed. In any event, this did not raise alarm bells at the Armenian Ministry of Nature Protection. Their reply is that the information is filled in based on the applications it receives from the legal entity in question.

While the Zoo Fauna Art name appears in a minority of documents, most of the export/re-export permits from Armenia were issued to Armen Khachatryan, Artur Khachatryan’s brother. He is a citizen of Russia and he sent himself more than 50% of the monkeys, 60% of the parrots and some 70% of other birds exported from Armenia. (See the interactive info-charts)

At this point, we cannot say if Armen Kazaryan, also registered as residing in Russia, is the partner of Artur Khachatryan or not.

Hetq tried to contact Zoo Fauna Art owner Artur Khachatryan for answers regarding questions arising from information in the text. However, Khachatryan response was, “I have nothing to say to you. Goodbye.”

In response to our telephone call, a statement appeared in a website (later removed but which can be accessed here) regarding “the only regional zoo-breeding facility” in which Khachatryan claims that the reason work on the breeding facility has been halted is the fact that “certain news outlets in Armenia have been spreading charges and slander regarding his name…”

In the same statement, Khachatryan says that he lived in the UAE for many years and has engaged in business for about twenty years.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment