Dersim - Armenian Folk Medicine

Author: Adom H. Boudjikanian, Translator: Simon Beugekian

What is folk (or traditional) medicine?

According to the United Nations’ World Health Organization (WHO), folk or traditional medicine consists of all medical practices traditionally used to prevent, diagnose, treat, and/or cure diseases, as well as all practices designed to improve one’s physical and mental well-being. These traditional practices may be based on a society’s unique cultural norms and standards; may be passed down from previous generations; and may or may not be scientifically or empirically justified [1].

Besides the preparations derived from medicinal herbs and those obtained of animal parts, folk medicine also includes acts whose effects can be evaluated only subjectively, such as pilgrimages; bathing in springs that have been ascribed medicinal properties; or the use of ancestral, pagan methods, such as the wearing of talismans and charms. Historically, there were even cases of Christian Armenians seeking Muslim mullahs, believing in the curative abilities of their prayers.

Folk or traditional medicinal practices often conflict with modern, scientific, and western medicine. In fact, practitioners of folk medicine usually believed that modern medicine did more harm than good, due to its use of non-natural remedies. However, in many other cases, traditional medicine is used in conjunction with more orthodox methods. The WHO sometimes even encourages the use of traditional practices alongside more modern ones. Finally, in some cases, traditional medicine is used as a matter of necessity, especially when financial constraints preclude the use of costly modern medications and practices. This was certainly case in the Province of Dersim.

Challenges to Research

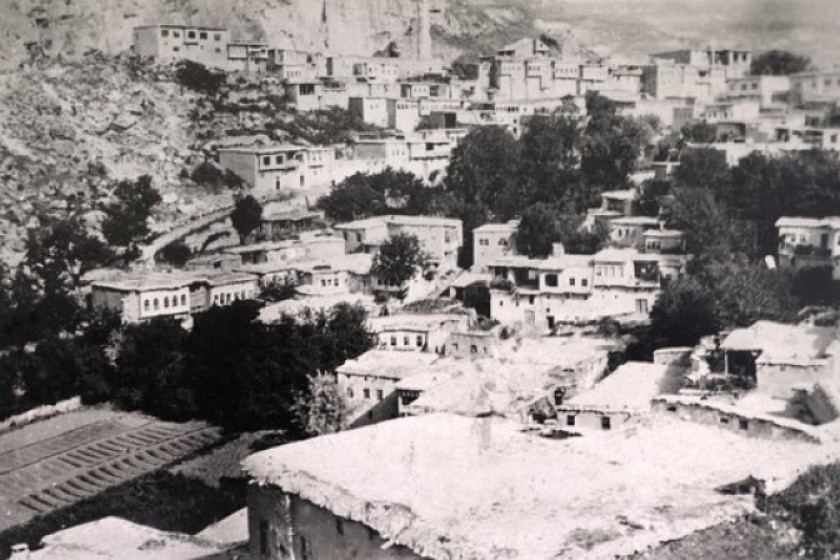

In the final years of the Ottoman Empire, the Province (Sanjak) of Dersim was divided into six districts (kazas). Of the six districts, I was able to find information about two – Charsanjak and Çemişgezek, both with large Armenian populations, and both located in the Dersim Plateau (1,000-2,000 meters above sea level). I was unable to gather information of the same quantity or quality on the other districts of Dersim.

The mountainous areas of Dersim were located at an altitude of 3,000-4,000 meters above sea level. Many of these regions were created by volcanic processes, and as a result, featured many natural springs that were through to have medicinal properties.

The Province of Dersim was rich in water, given that it was crossed by multiple streams and rivers. Thus, medicinal herbs and plants were featured heavily in the region’s traditional medicinal practices, and the presence of those medicinal herbs and plants was a direct result of the geography and topography of the area, including the waterlogged soil favorable to the growth of various plants and herbs.

According to the principles of phytogeography, the flora (legumes, fruit-bearing trees, vegetables, and herbs) of the Dersim Plateau would be generally uniform, and thus their medical applications throughout these regions should be alike. It is also reasonable to assume that the mountainous parts of the area also featured similar flora and the incumbent popular medical practices. Additionally, it is safe to assume that the area’s Armenians, Turks, and Kurds used very similar medical practices.

An Overview of Health Conditions in Dersim

The majority of the inhabited areas of Dersim were located at an altitude of 1,000-2,000 meters above sea level. Consequently, the province featured many forests that purified the air; many sources of potable water sustained by the melt-off of winter snows on the mountains; and a climate conducive to the growth of various grains, vegetables, and fruit-bearing trees. Given such conditions, one would expect the people of Dersim to be hardy and to be blessed with longevity. One would also expect the population to grow exponentially.

We know that until the very last years of the Ottoman Empire, there were no practicing doctors in Charsanjak, and no functioning apothecaries in Perri. A rudimentary form of medicine was practiced by old women, using ingredients and herbs obtained from local attars (peddlers), such as castor oil. Barbers also offered medical services in the markets, and practiced both bloodletting and leeching.

The region was periodically devastated by outbreaks of endemic and childhood diseases, including malaria, tuberculosis, measles, smallpox, and whooping cough. Young couples in Dersim soon established large families, but over the years, many of their children would fall victim to illness. For example, over a period of twenty years, a mother would bear 10-12 children, of whom only one or two would survive to adulthood. Kevork Yerevanian, one of the chroniclers of Dersim, tells of Mako Baji, who had 30 children, all of whom died in their youth [2].

According to Yerevanian, the people of Perri, due to their almost exclusively carnivorous diet, were cursed with especially short life spans. Yerevanian approximated that life expectancy in Perri did not exceed 45 years. The people of Perri were convinced that “where meat enters, a doctor doesn’t” [3], which is in direct contradiction to another well-known popular adage, “an apple a day keeps the doctor at bay.”

From the modern perspective, Yerevanian had good reason to think that a heavily carnivorous diet and short life spans were correlated. Many epidemiological studies have shown that the heavy consumption of red meat contributes to higher rates of cancer of the stomach and the colon, as well as heart and cardiovascular diseases [4].

In relation to health, it is also important to note the salubrious conditions that existed in some areas of Dersim. Ghazarian states that beginning in the 1880s, in Çemişgezek and its surrounding Armenian- and mixed-populated villages, “modern” two-story stone homes gradually began replacing the traditional ground-floor habitations where animals and people lived together, and where diseases thrived [5].

On the other hand, in other areas of Çemişgezek, people still lived in ground-floor, earthen homes. These homes were vulnerable to rats, and the puddles of water around them contributed to the growth of large colonies of flies and mosquitoes that spread disease.

Yerevanian describes another practice harmful to health. In the winter, to shelter from the cold, entire households would gather in their homes’ hearths, which were often kitchens, living rooms, and bedrooms combined, would shut the few windows, and would breathe in the fumes of their kerosene lamps [6]. It is not hard to imagine how easily diseases could be transmitted to old and young in such a fetid environment.

Traditional Medicinal Practices in Dersim: Diseases and Treatments

Doctors visited the Armenian villages of Dersim only on rare occasions. In some cases, Armenian peasants died without ever having been examined by a doctor in their lives. Thus, traditional medicine was the only resort for most peasants. There were experienced midwives and bonesetters in the villages, but the foundation of medical practice remained ancestral knowledge, passed down from one generation to the next, and practiced widely by the public. As in many other cultures, the people of Dersim were convinced that disease could be caused by supernatural phenomena, such as an “evil eye” cast upon someone by a jealous rival, the “evil spirit” they often called “El,” etc.

Since supernatural causes were often considered the causes of disease, it is natural that the people resorted to superstition to stave it off. In Dersim, as in other areas of historic Armenia, pilgrimages (to monasteries, mountains, tombs, and natural springs) and animal sacrifices were seen as a means to ward off the “evil eye.” The people also believed in the power of talismans. Alongside these practices, the people of Dersim also used herbology, as well as waters of natural springs, to treat disease and keep it at bay.

Miraculous Waters

The people of Dersim were unaware of the modern scientific practice of water therapy. For instance, there are many scientific ways to explain the palliative effects of balneotherapy – the regulation of blood circulation and heartbeat, changes in hormonal secretions, and the detoxifying effects of sweating and the expulsion of toxic substances via urine. The shock caused by the quick, successive exposure to heat and cold also has a “numbing” effect on the sensation of pain. This effect is based on the theory of counter-irritants, which is also the basis of many modern topical analgesic preparations.

The waters of the natural springs in Dersim, many of which had volcanic origins, were rich with macro-and micro-chemical elements. The salts of these waters were absorbed in the body of bathers via the skin, as well as through the breathing of the aerosol-ed droplets [7].

The people of Dersim, like many of our own contemporaries, believed that pilgrimages to natural springs, monasteries, and other holy sites healed and prevented disease. Here is a short list of those sites:

The Natural (Volcanic) Springs of the Baghin Mountain. The water was rich in iron and sulfur. Those who suffered from rheumatism visited this spring [8]. Sulfur contributes to the healthy growth of cartilage in joints, ligaments, and tendons [9].

The Sourp-Ag (Sovouk-Ag) [Holy spring] Natural spring [10].

The Noroyents spring in Perri. The water was thought to cure those who were suffering from “shivering.” Children and adolescents, some coming from faraway places, would bathe in these waters on Christmas Eve to stave off the “shakes” that many of them suffered during the year. After bathing in the waters, they would “leave their shakes behind” by tying a piece of their clothing to the branches of the Whitebeam tree (Pyrus, or Sorbus aria) that grew at the head of the spring. This practice of tying pieces of cloth to branches of “holy” trees was commonplace across the many holy sites/medicinal hot springs of historic Armenia [11].

The “shakes” were a symptom of malaria. Malaria was spread in the region by the mosquitoes that bred in the swampy areas of Dersim, such as Perri [12]. When bitten by the female mosquitoes, people’s red blood cells became infected with the unicellar protozoan parasites that cause malaria. These parasites go through their life cycles within the bodies of infected individuals, causing various symptoms of different intensity, including fever, headaches/body aches, excessive sweating, delirium, and intense shaking [13].

The shaking of malaria patients is a reaction of the body to the disease. As a result of the shaking, the muscles of the body tense up and the body’s temperature rises. Excessive shaking can also lead to sores in the tendons of the muscles, resulting in pain. Conversely, bathing in cold water relaxes the muscles, and enhances the patient’s immune system by stimulating lymphatic circulation. Yerevanian states that to treat high fever, the people of Dersim would cover the patient in many blankets to induce heavy sweating, and place towels soaked in arak on the patient’s forehead. Yerevanian also writes that Sulfato (a type of sulfonamide) was used to treat fever [14]. This seems rather odd, given that the first sulfonamides were discovered in 1932-1935.

The Mermaid’s (cherahars’) cold spring. It was located near the monastery of the village of Akrag in Dersim (District of Khozat). Those who suffered from blocked ears and other ear troubles dripped the water of the spring into their ears. The patient would also light a candle and place it on the holy rock near the spring [15].

The Khosdoug spring. Children who suffered from abdominal pain were taken to Khosdoug in Pazaron (in the Charsanjak district). The children would bathe in the waters and drink from the spring. As for adults suffering from abdominal pain, Yerevan writes that they would be treated at home. They would be given arak to drink, and if the pain worsened, a hot rock would be placed on the site of the pain [16].

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment