OVIR – No Exit for Outsiders (Part 1)

When you ask a former repatriate to Soviet Armenia about OVIR, the person most likely responds with a grin. Today, we can’t understand how a person can crack a grin when hearing the name of OVIR (the passport and visa subdivision of the Soviet Ministry of the Internal Affairs), even after living overseas for half a century. In fact, it’s a self-defense mechanism against the not too distant past.

OVIR was that “needle-like corridor” through which Soviet citizens had to pass to travel or resettle overseas.Created at the end of 1935, OVIR seemed to be on a paid vacation until the death of Stalin and the denouncement of the cult of personality.It only serviced Soviet citizens going abroad on special, important, work, or foreigners visiting the Soviet Union. The number of both was quite limited. Wary citizens of the USSR, with a modicum of rationality, would never even dare approach the OVIR office.

To be sincere, there was no great desire to visit the office anyway, given that communist propaganda had created a mindset according to which the world was black and white, light and dark, good or evil. So, what sense did it make to leave the white for the black, the light for the dark, and prefer evil over good?

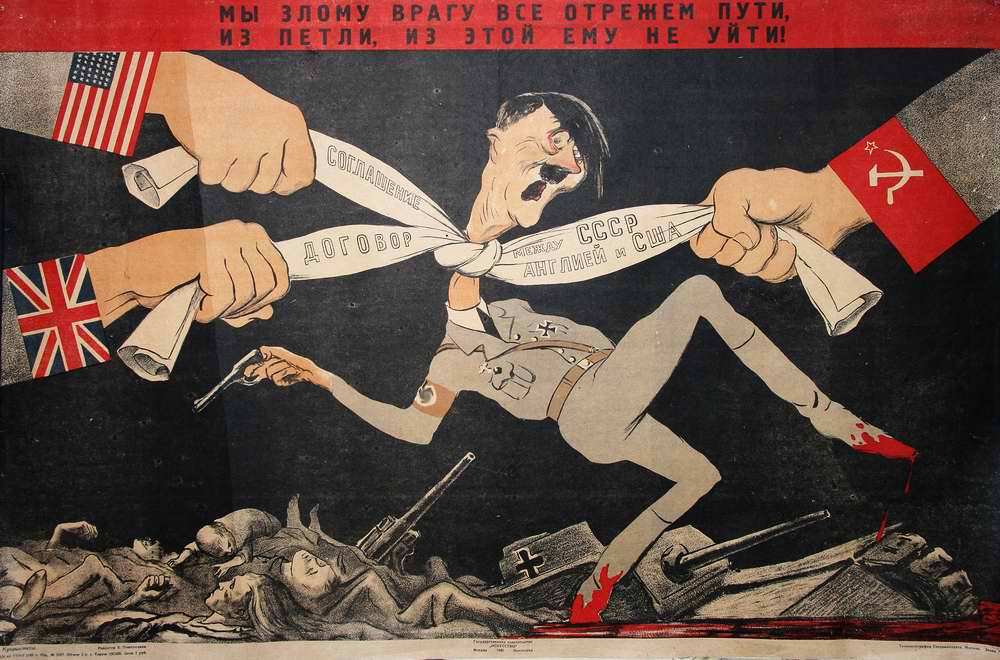

The advent of WWII lessened the existing antagonism to a certain degree. When the U.S. and Great Britain allied themselves with the USSR to battle Nazi Germany, Soviet propaganda began to speak in reverentially about the “lands” on the other side of the Iron Curtain. This didn’t last long. Friendship was temporary and targeted against the common threat.

OVIR wasn’t a “welcoming haven” even in the early Khrushchev period. Over the years, the department was periodically transferred to the control of the KGB or the Ministry of the Internal Affairs. Even this “wandering” and the name of the KGB was enough to keep OVIR, intimidating on its own, completely inaccessible.

In the 1950s, certain repatriates, buoyed by the freedoms of the post-Stalin era, started to petition US and French consular services in the USSR. Requesting permission to leave, they were surprised and disheartened when told to apply to the local authorities. Apply to whom? How? Who would listen to them? What reason could they give that wouldn’t be regarded as a stab in the back to the fatherland?

Given that the Soviet Union implemented a relatively open international policy during the Khrushchev era and attempted to play the role of initiator in global peace and security issues, it was forced to make certain concessions. While frequently made for show and to pull the wool over the eyes of the West, even in this case, the official ideological resistance of the USSR gradually weakened.

By the end of the 1950s, OVIR was no longer off limits or inaccessible. Many repatriates, especially Armenians from America and France, steadfastly attempted to leave. OVIR had truly become something of a game of chance. One could gamble, but winning wasn’t ensured. That people could attempt to leave allowed Soviet authorities something of an argument it could provide its Western partners. Look, the Soviets explained, people are not deprived of their right to express a desire to leave. Whether permission is granted or not, the argument went, was merely a procedural, not a political, matter.

To apply to OVIR, one needed an invitation from a close relative living overseas. To get that invitation, a person had to first write to the relative. Writing such a letter and sending it by post wasn’t the smartest thing to do. Everyone knew that the mail was inspected and that undesirable letters often never reached their destination.

Harout Barsamian, a former professor at the University of Irvine, California, now deceased, recounted that the family sent a letter in 1964 to a cousin living in America for an invitation with a drummer in Charles Aznavour’s group that was on a concert tour in Armenia. “But even then, we didn’t write openly about the invitation. We wrote that if it was possible, my uncle should come to Armenia. He had the money and came. It was in Yerevan that we told him to send an invitation,” Barsamian recounted.

But even having an invitation wasn’t enough of a guarantee that an exit permit would be granted. There were a thousand reasons for refusal. For example, let’s say there were two brothers. One lived in Soviet Armenia, the other, overseas. If the brother on the outside died before sending the invitation, the family back in Armenia lost its chance to leave. The invitation sender had to be a relative of the first order.

In the case of an acceptable invitation, any past dealings with Soviet security services could be used as a reason for refusal. If a person became the target of KGB attention, whether for serious or minor reasons, that person would be classified “unqualified for leaving” (Russian невыездной)։

Mardiros Vartanian, who immigrated to Armenia from Syria in 1946 and now lives in Glendale, California, was a lecturer at Yerevan’s Polytechnical Institute’s Department of Mechanical Engineering. He had problems with the KGB for telling his students stories about the Armenia fedayee (volunteer fighters) during class. He was issued several warnings, summoned for a talk, and later was forced to leave the institute. He applied to leave for America. “They denied my request for years. I was ready to resolve the matter with money, a bribe. But it didn’t happen. I had given up on the idea of leaving and wanted to get a job somewhere.

My friend, who was also a friend of Karen Demirchyan (the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Armenia, 1974-1988), paid Demirchyan a visit and told him that I wanted to leave and was refused. My friend told him I was a specialist and asked for a job. Demirchyan also knew me quite well. Demirchyan said, ‘If he wants to leave, good riddance. What kind of work will he do?’”

Even if one had an acceptable invitation, having any ties to secret organizations was an even greater reason for being denied an exit permit. There were many in this category and denying them an exit permit didn’t take much. Refusals were on the level of state security, even though Harout Barsamian told us differently in our interview.

He said that a special five-member committee would discuss the cases of those possessing state secrets. On the committee were representatives from the Communist Party of Armenia’s Central Committee, from the Council of Ministers, the KGB, and the interior and justice ministries. “It turned out that all those representatives knew me and said that I should be permitted to leave. It was later that I found out who they were,” Barsamian recounted.

We have no reason to doubt what he says, but out comprehensive searches and meetings with former Soviet officials have not confirmed the existence of such a committee.

To be continued

………………………….

This article is prepared within the framework of “Two Lives: The Cold War and the Emigration of Armenians” project financed by National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment