Armenia's Shvanidzor: Remains of the Past

By Lillian Avedian

I sit across the table from an old village man, the skin of his face sagging from the weight of his experiences and his white hair clinging to his head.

He wags his finger frantically as he carries on the rant he has been delivering for the past hour. I listen intently, desperately trying to make sense of his jumbled thoughts while endeavoring to throw in a question or two of my own, yet I am foiled in my plan. He has already decided what he wants to say, and I serve merely as a listener.

"A majority of Turks are animals," he growls. "When you're facing an enemy, who wants to destroy you, the only solution is to take up arms and fight."

He continues on in this vein, repeating the same disturbing ideas. That Turkish people are evil, and that their cruelty is embedded in their genetic makeup. That the only way to face evil people is to eliminate them. That Turkish people learned culture and civilization from Armenians. That most Armenians are good, except for a few animals who also need to be eliminated.

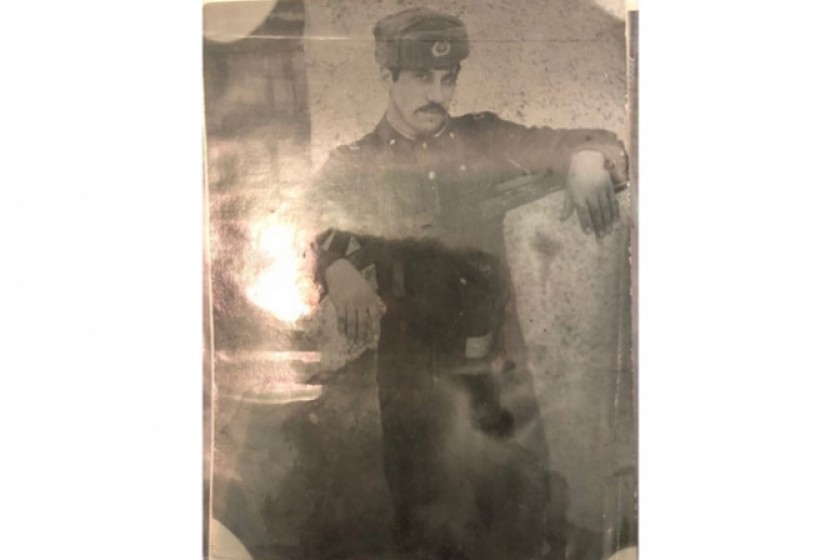

I feel unnerved by his assertions and try to shift the conversation by asking about his personal history. He explains to me that he served in the military in Russia in the 1970s and was elected the head of the village of Shvanidzor from 1988-1994. He led the village during the Nagorno-Karabagh war of the early nineties, stationing Armenian soldiers in the mountains in order to instill fear in the Azeri people who lived in Shvanidzor, forcing them to flee to Azerbaijan (according to his account). After ending his term, he served in the military at the border from 1994 to 2010.

"Beyond anything, what will last throughout history is your name," he claims.

I assure him that he has served his country well, and that he will be remembered as an honorable man and a patriot. He seems desperate to prove his honor, to justify all that he has sacrificed for the defense of Armenia's borders. He kindly accepts my assurance, and I hope that this will be enough to move on from this topic.

However, his recollection of his time as a public servant and military leader triggers his hatred for Turkish people. He resumes his angry tirade, against Turks, against Azeris, against the greedy and the corrupt and the powerful. He becomes repetitious, defending his years of service, his honor, his patriotism.

While he talks, his wife joins us at the table (after having set the table with coffee and chocolate and fruit of course). At moments she attempts to interject, to support his views with her own, and they shout over each other as he shuts her down, loudly proclaiming his opinions while dismissing hers. At this point I am deeply uncomfortable with this exchange and know I will take away nothing from this interview if it carries on this way.

"Do you have any old family photos?" I finally blurt out, eager to salvage our conversation.

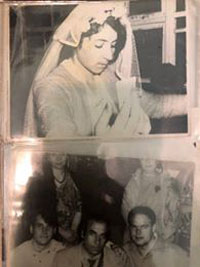

His wife rushes to the bedroom and returns with several photo albums. She happily flips through the albums, pointing out young photos of herself, of her husband, of their wedding day, of their children.

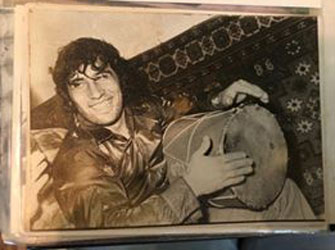

At this point, the old man's face changes. His hardened scowl melts away, and his eyes begin to gleam with the memory of his youth. His wife shows him a young photo of himself from the seventies playing a "dhol" with scruffy hair that covers his eyes, and he laughs, making a joke about his terrible style. He tells me about his love for music, pointing out a photo of his father and his wife's father playing instruments together and explaining that they were both self-taught, like himself. I gawk over a photo of his wife on their wedding day, and he smiles, commenting upon her beauty.

"Those were the good old days," he sighs. "And now they're gone."

Flipping through the photo albums, I am struck by the overwhelming number of military photos. Over half of the photos are composed of group shots of men at the border, of the old man posing in his uniform, of the old woman dressed in her own attire as a military cook. Of their two sons and one daughter in their own military attire stationed at their posts.

The old woman leaves and returns with a stack of certificates rewarded to the family for their military service. She proudly shows off each one, and I take the time to look at each and praise the family, even though the certificates are written in Russian and I can't read any of them.

Looking at these photos, at these certificates, at the old man's change in demeanor, I begin to understand his anger. I see that while he fumes against the cruelty of the Turks, he sees before his eyes the gunfire and blood and smoke that he faced every day at the border. He hears the ringing of gunshots and the wails of the dying. He envisions an enemy at the other side of the border who brings forth this incomprehensible violence and suffering.

Looking at these photos, at these certificates, at the old man's change in demeanor, I begin to understand his anger. I see that while he fumes against the cruelty of the Turks, he sees before his eyes the gunfire and blood and smoke that he faced every day at the border. He hears the ringing of gunshots and the wails of the dying. He envisions an enemy at the other side of the border who brings forth this incomprehensible violence and suffering.

The old man lives in his memories of conflict and warfare, and they are etched into his mind even as he walks through the quiet of his village or sits at a coffee table with a young woman. He can never escape from the fear he felt as a soldier, and so now he lives with constant rage. He has sacrificed his youth, his family, his happiness to the war effort, and the advancing soldiers are to pay.

Speaking with this old man elucidates for me the causes behind much of the racist anti-Turkish rhetoric ever-present within the Armenian community, particularly in this small village in the southernmost corner of Armenia.

Shvanidzor gives up at least a few of its boys to the Armenian military every year, due to the mandatory military service applied to all of Armenia's eighteen-year-old men. When a village must sacrifice its people to a war effort that kills many of its youth, it is easy to blame those who have been labelled the enemy for decades, who are faceless and nameless except when they are firing upon you. Ethnic hatred takes root and flourishes when security is not guaranteed, and when people are bound to a war waged by faraway governments.

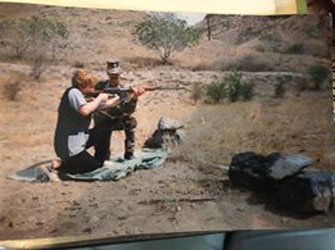

The militarization of Shvanidzor is evident from the nationalistic songs about the heroism of Armenian soldiers the children love to sing, the mandatory firearms class children are required to attend, and the photos of deceased soldiers posted all around the walls of the village's school. And while the youth are more apt to engage in discussions of race and the error behind fueling ethnic hatred and "enemy" discourse, those in the older generation like the man I sat down with whose lives are defined by fear and pain could never comprehend such conversations.

As I leave the old couple's home, they tell me that their doors are always open to me, and that if I ever return to Shvanidzor, I am always welcome to stay with them.

I don't know if I will ever return to this house of memories haunted by the past and kept alive with anger. Yet I certainly will never forget it.

(Lillian Avedian is a student at the University of California, Berkeley studying Peace and Conflict Studies and Armenian Language and Literature. This is her second article in a series of articles overviewing life in Shvanidzor, a village in the southernmost corner of Armenia.)

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (2)

Write a comment