The Anzacs and the Tattoo Artist of Jerusalem

By Arthur Hagopian

Jerusalem, 70 years ago.

The fighting is over.

The curtain has gone down on the horrendous carnage of World War II and the foreign troops, among them the ANZACs (members of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) whose legendary heroism have helped turn the tide and contribute to the Allied victory, are sailing back home, laden with the pathetic paraphernalia of war: wounds and scars, exotic souvenirs (some of them admittedly fakes), a few scraps of the guttural languages spoken by the inhabitants of the region (interspersed with expletives, inevitably), and painful memories of an unforgettably horrent experience.

They would be leaving the Middle East, never to return for most of them. But not to forget. They have lost too many mates for that.

As they make their final preparations for departure, some of the ANZACS avail themselves of a last opportunity to salvage a modicum of cheer from their desolate ordeal, and have a one last hurrah: hopefully, their luck might hold and they might come across some houry-eyed “bint" and carry back with them her scent and memory of a cursory dalliance, to atone at least partially for the stench of war.

A raucous bunch, some brazenly sampling the delights of the delectable wines of the Latroon abbey of the silent Trappist Brothers, or singing a discordant rendition of Abe Olman's popular "Oh Johnny, Oh Johnny, Oh!", they set out on a stroll down the cobblestoned alleys of the Old City of Jerusalem.

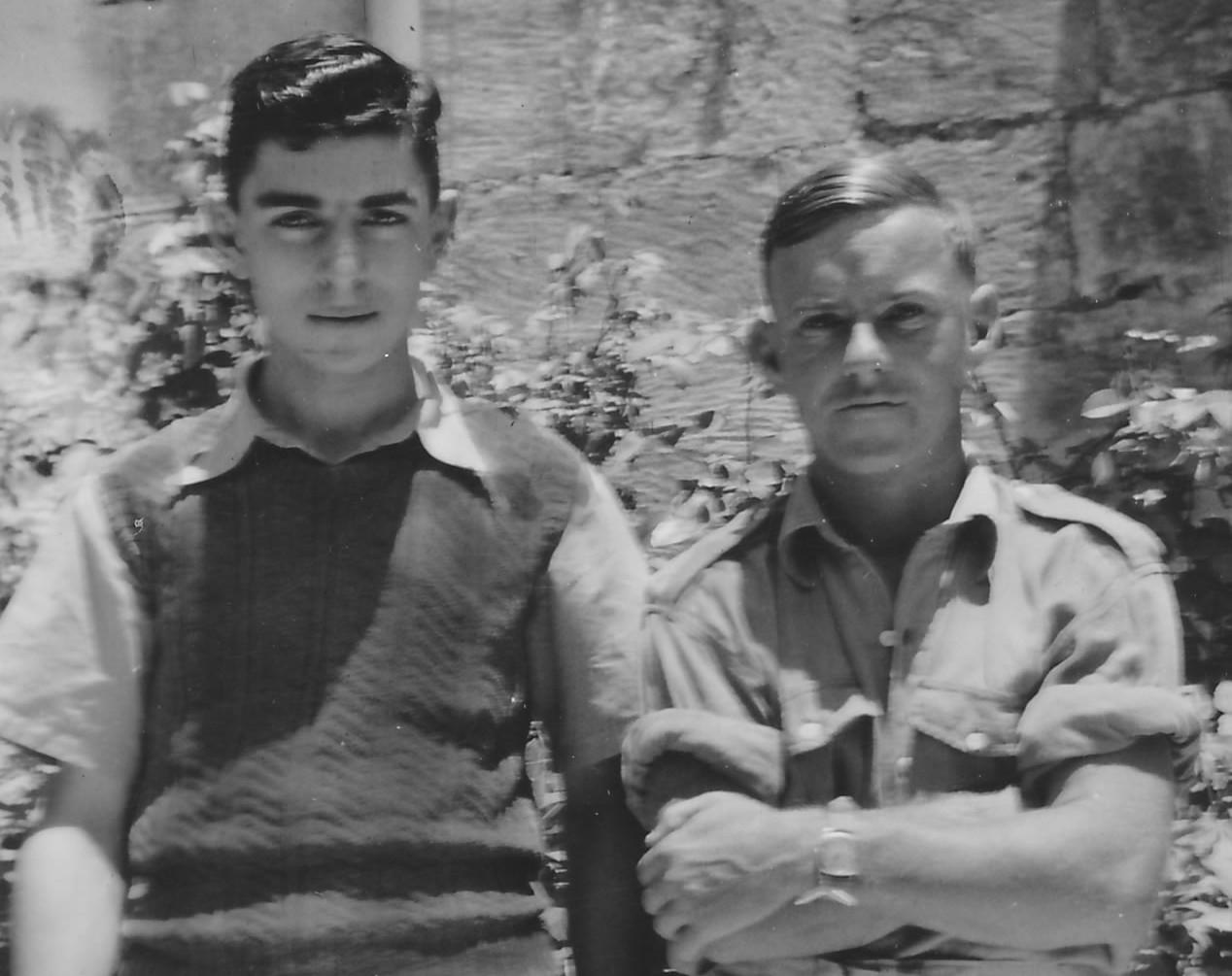

Among the ANZACs are New Zealander sergeant Dick McCleod, and an Aussie named Butler.

For them, this would unequivocally turn out to be the epitome of a traumatic Middle East idyll and walking in the footsteps of the prophets would help to rejuvenate their faith and lift up their spirits.

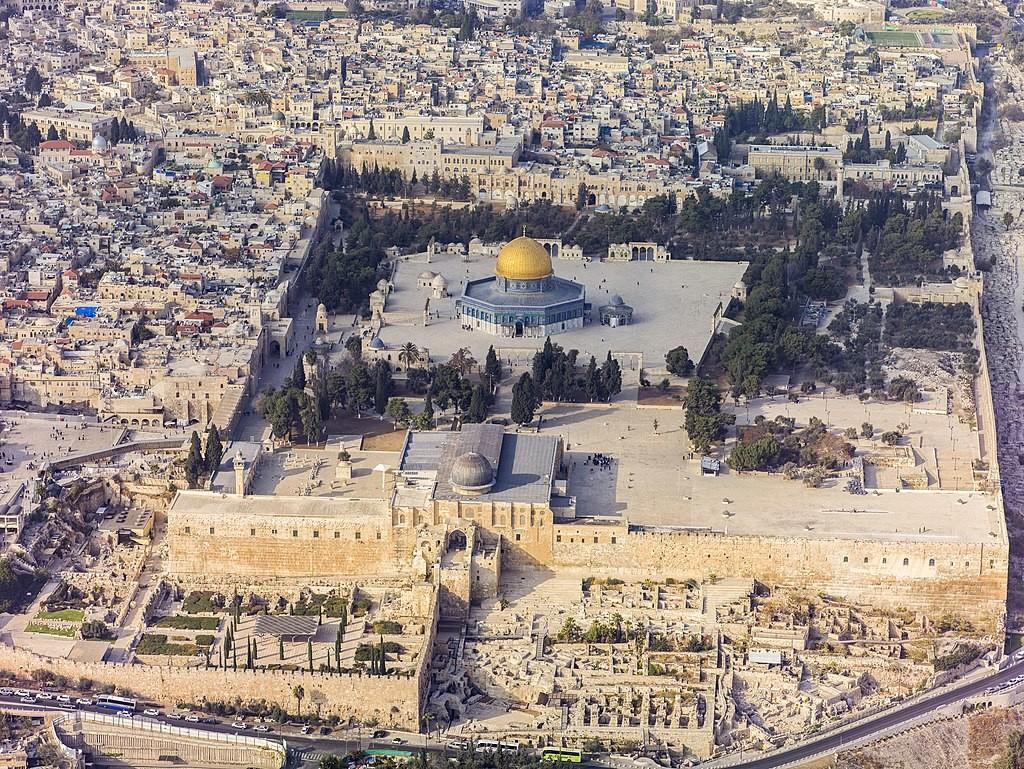

As the company meander their way on their joyous errand through the twisting streets and alleys of the city that is sacred to the three great monotheistic religions of Christianity, Judaism and Islam, little do they realize that every tile they tread has a tale to tell: tales of bloodshed and glory, of victory and defeat, of triumph and despair.

This is the route the ancient prophets followed. Here, along the Via Dolorosa, Jesus trudged towards Golgotha, bent down under the weight of his onerous cross.

The ANZACs have no ultimate destination - they are strangers in this strange land and walk where their feet take them.

Along the way, they come across people from some of the world’s most intriguing ethnic groupings: Armenians, Jews, Arabs, Greeks, Ethiopians, Copts, Moroccans, Indians along with scatterings of fellow Anglo Saxons. In their euphoric mood, the ANZACs enjoy fleeting contacts and exchanges of snippets like "Shalom", "Al Salaamu Aleikom," "Kalispera" while a few of them even engage in a decent, albeit halting, dialogue with the natives many of whom speak English.

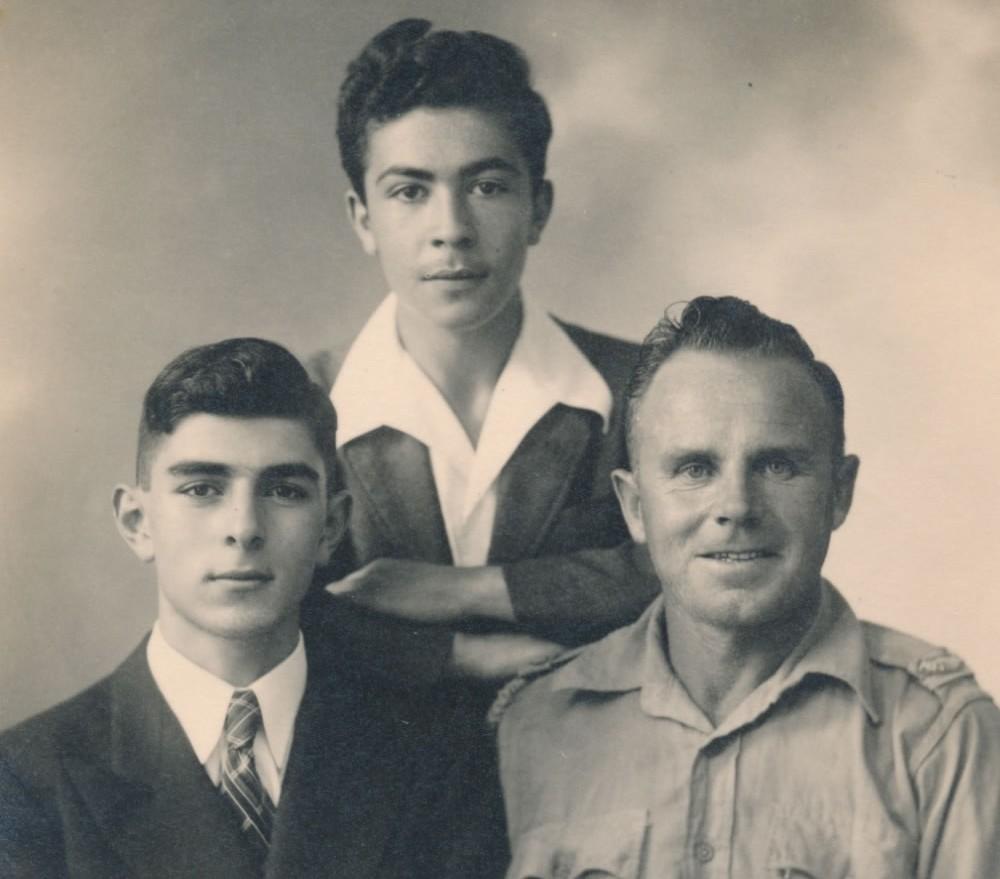

Their peregrinations bring them to a nondescript little shop where a teenaged Armenian tattoo artist, Barouyr Hairabedian, plies his age-old trade.

Barouyr had begun honing his skills, practicing on cucumbers and on his father, at the age of 11, to help defray the cost of his school fees. And at the age of 14 years, he got an opportunity to demonstrate his prowess on an amused but obliging Aussie soldier.

His daughter, Sona Hairabedian, takes up the tale.

"My father began working around 1938," with the baying of the hounds of war in the air.

"The soldiers who came to the tattoo shop were Australians and New Zealanders. A few of them became friendly with my father's family and spent time with them," she tells me.

Barouyr's uncle Alexan had inherited the shop from the original tattoo artist, Nerses, who was also a goldsmith. When he died, Barouyr stepped into his shoes.

Nerses tattooing a lady

The shop was located opposite the entrance to the Convent of St James, seat of the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem whose cathedral is recognized as one of the most magnificent churches in the whole Middle East.

"My great-uncle Alexan began working for Nerses about the year 1898, helping with metal work and tattooing, mostly pilgrims. Nerses was guarded about the secrets of his goldsmithing craft and would send Alexan out on errands whenever he had something to do that involved a proprietary technique. But somehow Alexan mastered the craft and carried on the metal work and tattooing business after Nerses died," Sona relates.

The diminutive Alexan (he suffered from severe scoliosis), was "clever, industrious, and an excellent story-teller. People visited his shop just to chat and listen to his hunting tall-tales. He was fond of animals and had raised a pet rooster in the shop. It roamed around the place freely, guarding the premises like any dog, strutting in and out as it please," Sona adds.

According to Sona's father the first wave of Australians who came to Palestine in WWII were volunteers, “and a rather raucous group." British draftees were to arrive later.

"My aunt Alice recalls enjoying the imported canned Australian cheese (ed: most probably Kraft) her father used to buy during the war," Sona notes.

Sona, a professional graphic designer and web developer, who lives in New York, is a scion of the "Kaghakatsi" ("native town dwellers") community of Armenians who have been living in the Armenian Quarter of the Old City for 2000 years, in the process setting up the city’s first printing press and photographic studio.

She says her father remembers Butler as a "humorous Australian" (he had been deployed to El Alamein) who, "and as a parting gift, brought toothbrushes and toothpaste for the family."

"Although I can't identify Butler's brigade, it seems likely that he was with the 2nd AIF (Australian Imperial Force), 9th Division, which was sent to Palestine for training, and later saw service at El-Alamein," she says.

When the Aussie contingent first set foot in Palestine, they "rather shocked the natives by drinking in the streets," she says. "I suppose that wouldn't have gone over well with the local Muslims."

Before long, military police put short shrift to their shenanigans. Those who continued to misbehave were hauled off to jail in a building located on the hill above the old Bishop Gobat School (today's Jerusalem University College).

Jerusalem lies dormant for most of the year, cocooned in its millennia of history, but springs to life in a glorious manifestation of daffodils and religious euphoria during Easter. The town sheds off its languid torpor to put on a garish display of candles and lanterns, Easter eggs, giant umbrellas, corn on the cob and pilgrims bedecked in their countries' technicolor palettes.

Merchants anchor their wares anywhere they can find a nail, cordoning their shops and stalls with herbs and silk, to the delight of the throngs.

This was the time of year Barouyr and one or two other tattoo artists found the most exhilarating, and exhausting, as they tended to the innumerable patrons seeking their services.

Barouyr fondly recalls the stoic Aussies who would endure the painful needle jabs (since most tattooing was done by hand needle-prick by needle-prick), without any complaint.

It was a British officer who would provide their salvation.

Once, while Barouyr was tattooing the British officer in this tedious, painful style, the officer remarked, "Why don't you get yourself a machine to do this? It's based on the same principle as a doorbell."

Barouyr had just learned about the structure of doorbells in his science class at Bishop Gobat School, and had built one as a school project.

He promptly went to the Jewish Quarter nearby and purchased a new doorbell, modifying it to power the tattoo pen.

"This was around 1940. By the time the war started, and soldiers ranged the city, he was able to handle the demand for the bigger, multi-colored designs, this time adding pin-up girls to his portfolio of cherubs and crosses, at the insistence of homesick soldiers.

"One afternoon Butler came to the tattoo shop, but my father was at home, having dinner. He had an arrangement with local Arab urchins, that if they brought him a customer, he'd pay them.

"On this occasion, a boy noticed the Aussie at the shop door, and led him to the Hairabedian house. My grandmother invited Butler to sit down and join them for dinner; and afterward, my father walked back to the shop with Butler to get his tattoo," she adds.

"That's how the friendship began. Butler was a cheerful, gregarious person who enjoyed being the life of the party. My aunt Alice remembers him singing 'Oh Johnny Oh Johnny Oh!' to a little cousin".

Sgt. McCleod was a "scholarly, gentlemanly New Zealander who was very interested in Old City Jerusalem and the Middle East in general. He was surprised and pleased to find English-speakers among the natives, and he was also a guest at the Hairabedian table," Sona says.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment