The Armenian-Speaking Muslims of Hamshen: Who are they?

By Vahan Ishkhanyan

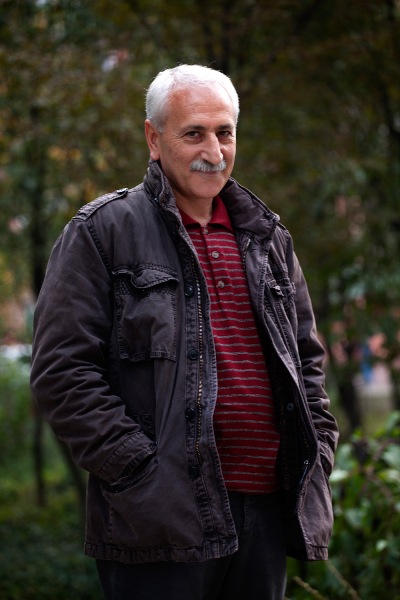

“I feel uncomfortable conversing through a translator. We can speak that language fairly well, but sadly we’ve been subjected to assimilation and various pressures. That’s why we have difficulty understanding each other,” says Yılmaz Topaloğlu, the former mayor of Hopa.

The language he refers to is Armenian. Yılmaz wouldn’t say such a thing to anyone else in the world except for an Armenian who speaks it - “I feel uncomfortable conversing through a translator.”

So here we are; two individuals who speak the same language but cannot understand each another. I am an Armenian from Armenia who has come to Turkey to conduct research about those Muslim inhabitants who speak Armenian.

|

Yılmaz – I feel uncomfortable talking through an interpreter |

Wherever I would go, the villages, the shops and cafes of Hopa, or to Çamlıhemşin (the center of the Turkish-speaking Hamshens[1]), the fact that I was Armenian immediately impacted my dealings with people. Sometimes the effect was positive, as in Hopa, where I received a warm reception along the lines of, “You’ve come from Armenia? We too are Armenian.”

There was also the flip side of the coin, as in Çamlıhemşin, when an old man’s smile disappeared when he heard I was from Armenia. The man also disappeared back into his house.

We could understand words here and there when Yılmaz spoke; sometimes entire sentences. Complete thoughts were hard to grasp. Our conversations had to be translated from the local Armenian dialect to literary Armenian or from Turkish to Armenian.

|

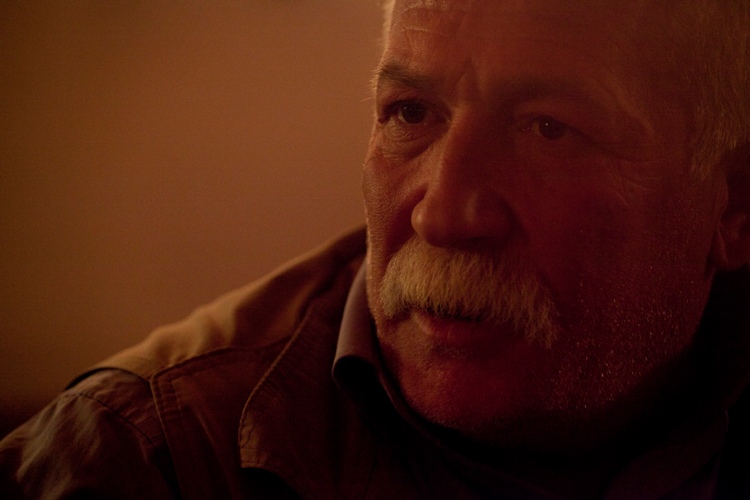

Truck driver Erdoğan – I have no doubt that we were once Armenian but converted to Islam some 400 years ago. I don’t know why we decided to become Muslims and other Armenians didn’t. And why didn’t the other Armenians want anything to do with us afterwards? |

|

“I have no doubt that we were once Armenians, but that we converted to Islam 400 years ago. Why was it that we decided to become Muslims and other Armenians did not? Before, we weren’t brothers, now we are”, says truck driver Erdoğan Yenigül. The man displays no antagonism when talking to us. Rather, there’s a smile on his face when he asks questions to which answers are not expected. In a bar in Hopa, Erdoğan switches from Homshetsma to Turkish. I understand a few words in the Hamshen language. Khachik Terteryan translates the Turkish. Anahit Hayrapetyan, our photographer, needs no translator. The language of the photo is universal.

The three of us – I, Khachik and Anahit – crossed the Georgian-Turkish border on a bus that plies the route from Yerevan to Istanbul. We got off in the town of Hopa, just 20 kilometers into Turkey. It’s the largest community of Armenian speaking Muslim Hamshens. For the next twelve days I searched for answers to the following – who are the Hamshens? Are they Armenians, Turks, or do they constitute a separate people who is neither?

I had read much on the subject but never found adequate answers to these questions before my trip to Turkey. I remained just as perplexed after returning to Armenia. Answers remained just as elusive.

Hamshen: Historical Note

Historical Hamshen is located in the northeast region of present-day Turkey, some 90 kilometers from the Georgian border. Today, there are two places bearing the name Hemşin, both in Rize Province. There is Hemşin (both a town and district) and the other is Çamlıhemşin, (also both a small town and district) where the Hamshens speak Turkish. The latter is a combination of the terms "Çamlı" which in Turkish means "pine-forested" and "Hemşin".)

On the basis of records of two Armenian historians from the 8-10th centuries, scholars now conclude that the Hamshens built their first settlements in the 8th century. Ghevont, a historian of the day, chronicles that 12,000 Armenians fled to Byzantium in order to escape the persecutions of Arab conquerors. The Armenians were led by Shapouh Amatouni and his son Hamam.

Ghevont relates that upon their arrival Emperor Constantine settled them in “a pleasant and fertile land”[2] Using Ghevont as a reference, Dr. Levon Haçikyan [Khachikyan], cites 789-790 as the year when Hamshen was founded[3]. The historian Hovhan Mamikonyan, in his History of Taron, notes that Hamam renamed the city Hamamashen (the city of Hamam). Two letters in the name were contracted, leaving Hamshen.

In this history, Hamam alerts Tiran Mamikonian, Prince of Taron, who is in alliance with the 7th century Byzantine Emperor Heraclius that Vashdean, Prince of Georgia, Hamam’s uncle, is in league with the King of Persia against him. The Prince of Georgia is so enraged to discover what Hamam has done that he has his feet and arms chopped off. Vashdean invades Hamam’s lands and destroys his city of Tambur. Hamam then rebuilds his city and calls it ‘by his own name’ Hamamashen.[4]

Levon Khachikyan argues that Hovhan Mamikonyan’s history is “fable-like”, since it was written one hundred or even two hundred years after the migration of the Amatouni's. (Scholars cite Hovhan Mamikonyan’s “Patmut‘iwn Taronoy [The History of Taron],” as a work of the 7th - 9th centuries)[5]

According to Khachikyan, since the Amatouni’s governed the provinces of Aragatzotn and Kotayk, the Hamshens migrated from those areas. My father, the linguist Rafayel Ishkhanyan, made the following notation in his book Armenian Ethnography and Folklore, where Khachikyan talks about the Hamshens migrating from the Ayrarat plains:

“The Hamshen dialect reveals that the Hamshen Armenians are not from Ayrarat but indigenous.” The Hamshen dialect belongs to the western Armenian group of dialects, whereas eastern dialects are spoken on the Ararat plain.[6]

|

|

The village of Chinchiva near Çamlıhemşin: This was the area of the first |

For 700 years Hamshen survived as a semi-independent Armenian princedom, falling to the Turks in 1489. Davit, the last prince of Hamshen, fled to the province of Sper where he barricaded himself.[7]

The Islamicization process of the Hamshens began in the 1700s. Many scattered to settlements along the Black Sea Coast – Trabzon, Ordu, etc – to avoid religious conversion. There are no records preserved from that period as to why and how they accepted Islam. All such information was recorded some 100-150 years afterwards.

The Christian Hamshen community began to migrate from Trebizond and other towns towards the Russian shores of the Black Sea in the 1860s (present-day Krasnodar and Abkhazia). During the 1915 Genocide, the Ottoman Turks launched a policy of exterminating the Christian Hamshens, a portion of which were able to flee to Russia.[8]

Hovann Simonian notes that according to the Ottoman files, the overwhelming majority of the population of Hamshen province was Christian until the late 1620s. During that period the Christians were heavily taxed by Constantinople. In 1609-1610 alone, the Hamshen province paid 7,090 kilos of honey and 2,660 kilos of beeswax in taxes. Taxes shot up 50% in 1626-1627. Simonian says that one of the likely reasons for the conversion to Islam was to avoid the onerous taxes levied on Christians. He also links the conversion to the weakening of the area’s Armenian Apostolic Church diocese. A manuscript written in Hamshen province in 1630 notes the absence of a bishop at the diocesan center of Khach‘ik Hawr (also known as Khach‘ek‘ar or Khach‘ik‘ear).

Further proof of the decline of the diocese is the absence of any record of scribal production in Hamshen province for almost the next 200 years, until 1812.

Despite its weakened state, Khach‘ik Hawr survived until 1915. It was registered as a church in the documents of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople in 1913 and it is due to its presence that Christian Armenians lived in the nearby village of Eghiovit/Elevit until the “Great Calamity”. If you travel to this village, present-day Yaylaköy, located in the mountains some 35 kilometers from the center of Çamlıhemşin, you will neither meet any Armenians nor find the ruins of Khach‘ik Hawr.[9]

|

|

Harun – There’s a sheepskin in each |

During the 1900s, material on the Islamicization process started to be published and Levon Khachikyan comments on them. Ethnographer Sargis Haykuni describes the forced religious conversion of Armenians along the Karadere (Black River) near the Hamshen province in a series of articles entitled “Lost and Forgotten Armenians, Black River Dwellers” published in the journal Ararat in 1895.

- After two foiled attempts the Janissaries, under the direction of religious mullahs, were finally able to overpower Torosli, a Karadere village putting up the strongest resistance. The invaders killed resistance leader Der Garabed and all his followers. “The bewildered Armenian people were looking to Der Garabed when one of the mullahs smote his sword upon the priest’s head. The priest raised his arms in defense and they were chopped off. A second and third blow followed. The blood flowed and the priest fell to the ground. The other mullahs immediately began to hack up the body in order to instill fear in the Armenians. Most of the people resisted the Turkish mob and rejected their offers. The bodies of those who did toppled upon the remains of the good priest. A massacre broke out on all sides; women and children fell under the sword blows.” He then writes that the mullahs did the same in one hundred other villages. “Some had already fled, others were massacred. There were those who renounced their faith to escape the peril awaiting them.” Those who fled took the remains of Der Garabed and buried them in the village of Kalafka. There, Der Garabed’s son was ordained a priest himself, taking the name of his father. The son vowed that succeeding generations of the family would always provide a priest with the name Der Garabed who would secretly visit Karadere once a year to console the people. The vow was interrupted in the 1820s. The tradition was picked up by Davlashian Der Garabed, from another family, who in the 1840s preached and distributed myuron (holy water) to the Islamicized Armenians in Karadere and Hemshin communities.

Sargis Haykuni says that the Christian faith was kept by the old women. During a visit to the Hamshen region in 1878 he asked residents how they identified themselves.

- I asked one elderly man, “Why have you become a Turk?”

- He was a good-natured Muslim who, with a brooding face, began to relate the feats of marvel performed by Mahmet. I took an old woman aside and asked her the same question. Making the sign of the cross she whispered, “Let me die for the Armenian faith”[10]

Khachikyan also notes that Poghos Tumayian in his 1899 The Armenians of the Pontos: Geographic and Political Situation of Trebizond refers to a diary that tells about the forced Islamicization of Karadere. Khachikyan personally saw the diary and based on it cites 1780 as the year of Karadere’s Islamicization.[11]

|

|

Khavitz – The name’s the same but |

One segment of the Hamshens migrated from Hamshen proper to the Hopa region some 250 years ago in the mid 1700s.

Khachikyan notes that the Islamicization of the Hopa area Hamshens happened at approximately the same time. He bases this conclusion on an article published by Grigor Artsruni in 1887 in which it says that they became Muslim “60-100 years ago”; in other words 1780-1820.[12]

Turkish nationalist historiography states that the Hamshens are derived from Turkish tribes from Central Asia or elsewhere. However, no corroborating sources are cited. One such example is the 2006 doctoral dissertation of Tuba Aslan entitled “Social Structure and Cultural Identity of the Hamshens” delivered at Istanbul University’s Institute of Sociological Sciences.

Aslan writes: “In the past, the Hamshens, living in the same area with Armenians and following the same faith of Armenians in the eastern Black Sea region, are associated with the Armenian identity today. In reality, the Hamshens are descendants of the Christian Turkish Parthev (Parthian) nation. They came from Horasan in the 7th century CE and settled in the eastern Black Sea area where they lived self-sustained until the founding of the Ottoman dynasty. As for the Armenians, one portion left before and one part after the Ottoman dynasty.”[13] This nationalist Turkish view also holds sway over a certain segment of Turkish-speaking and Armenian-speaking Hamshens.”

****

The Hamshen people today can be divided into three main groups:

1- The Sunni Muslim Armenian-speaking Hamshens, (Hopa-Hamshens) who live in the Hopa and Borçka regions of the Turkish province of Artvin and call themselves, Hamshetsi or Homshetsi. (Some remained in the Soviet Union after the border with Turkey was delineated in 1921 and now reside in Kyrgyzstan and Russia’s Krasnodar district)

2- Sunni Muslim Turkish-speaking Hamshens (Bash-Hamshens) who mostly live in the Turkish province of Rize and call themselves, Hamshil.

3- The Christian Armenian Hamshens, who live in Abkhazia and Russia’s Krasnodar District. They speak the Hamshen Armenian dialect as well.

There are also Muslim Armenian-speaking Hamshens around the city of Adapazarı in the western Turkish province of Sakarya (near Istanbul), who fled Hopa during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878.

“The Hamshens of Adapazarı lead a dual life,” says Hamshen researcher Harun Aksu. “They pray like Muslims, are Turkish nationalists, but when they get drunk say that their grandfathers were Armenians.”

The Hamshens: Population Statistics

The Hopa-Hamshens, some 25,000 in all, live in 30 villages in the Borçka, and Hopa districts of Turkey’s Artvin province. Hamshens constitute more than half the 37,000 population of the Hopa district, including the sub-district of Kemalpaşa.

Hopa-Hamshens and Bash-Hamshens live side by side in the western Black Sea province of Sakarya (in the provincial center of Adapazarı and the districts of Kocaali and Karasu), where the number of Hopa and Bash Hamshens combined is around 10,000.

The total number of Armenian speaking Muslim Hamshens in the Turkish provinces of Artvin and Sakarya, and other cities, is about 30,000 – 35,000.

Hagop Hachikian’s statistics put the number of Bash-Hamshens living in Turkey’s Rize province at about 30,000.[14] Turkologist Lousineh Sahakyan cites 60,000 as the total number of Turkish-speaking Hamshens.[15]

Today, many Hopa-Hamshens and Bash-Hamshens live in the Black Sea towns of Trabzon, Samsun, Giresun and Ordu. They not only have dispersed to Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir but as far as Germany and the United States.

Kayaköy – Eating Yaghaloush in a Hamshen Village

|

|

Father-in-law and son-in-law: Cemal and Cemil |

“There’s a sheepskin in every Hamshen house,” says Harun, who lifts the pelt hanging from the door and spreads it on the floor. “They kneel on it and recite the namaz ,” he says and kneels to pray.

Harun is a left-wing atheist and often ridicules religion. He tells me that some Christian missionaries had come from Armenia to “bring them back” to the correct path. They irritated him. “We were able to get free of one religion and now they want to burden us with another.”

“Harun, I’m an atheist as well,” I say. It turns out we have more in common than just speaking Armenian. But he’s a Muslim atheist and they are circumcised. Of course, that has nothing to do with faith; it’s more tradition. Like it or not, I’m probably a Christian atheist. Who knows? No matter; religion disappears and what remains is the language.

In the village of Kayaköy (former Şana), near the town of Kemalpaşa, there are 130 households with a population of 500. Film director Özcan Alper was born here.

63 year-old Cemal Vayiç, (the father-in-law of Hopa researcher Cemil Aksu) says that the village goes back some 500 years. It was first populated with aghas and then the Hamshens settled there. The aghas oppressed the Hamshen and later, when the Turkish Republic was founded in 1923, the state forced all to live in harmony. There are just bits and pieces of oral accounts of the village’s history.

There is no history regarding any of the villages of the Hopa-Hamshen. You will never be able to verify when the Hamshens migrated to Hopa, why they moved, and what were the names of the first settlers. Maybe there are some documents in the Ottoman archives.

The sheepskin is Cemal’s prayer rug.

- Do you pray – I ask

- Once a week

- How do you deal with the fact that your daughter is an atheist?

- Just fine. There’s no coercion in this house.

On our first day in Hopa, we were sitting in an open-air tea house with our Turkish colleagues, Cemil Aksu, President of the Bir Yaşam (One Life) Cultural and Environmental Organization, and Harun Aksu. We were discussing the project and decided to leave for Şana that same day. We were headed to see Teciye, the mother of Cemil’s wife Nurcan, who is a master of Hamshen cuisine.

|

|

Teciye: Master of Hamshen cuisine |

The women prepared for the meal by first spreading a tablecloth on the floor. The table itself, a round one with very short legs, is then placed atop the cloth. We sat on the floor, in the round, and partook from a communal plate containing yaghaloush – the basic Hamshen meal. It’s a dish of curds and onion fried in oil and resembles fried cheese with its sharp tang. Other dishes included dolma, etc. But the new strange flavor was so enticing that you didn’t want to ruin it by eating the other dishes. My hand had a mind of its own, constantly dipping bread into the yaghaloush for me to devour. When was the last time I actually ate a meal with my hands?

And the khavitz... This too was unlike the sweet flour khavitz I was used too. It was made of flour, corn meal, cream and oil, but it wasn’t sweet like the stuff back home. So, Armenians and Hamshens have something in common when it comes to food as well.

Teciye sings a Hamshen song when adding spices to the food.

Chakhe gouka tadis gou / Rain is falling, you are working

Megan tsak lmanis gou / You look like a little mouse

Chanchaghane kednive / Above the River Chanchaghane

Otket pobik trchis gou / You are running barefoot

“We didn’t convert to Islam overnight,” says Cemal Vayiç. “Religion was used as a means to get ahead. Those families with an imam got on the good side with the authorities.”

Nonetheless, religiosity never became deeply rooted and according to Cemil Aksu there are only two Hopa mullahs in the entire area.

So, who are the Hamshens in terms of nationality?

|

Cemal Vayiç: The Hamshens are descended from Armenians. If Armenians interact with us more often, we will be able to improve our language skills.” |

|

“I consider myself Hamshen,” says Cemal Vayiç. “We knew that language as young kids and want to preserve it. We aren’t renouncing our identity. I will live as a Hamshen till the end. We know that the Hamshens are descended from Armenians. If Armenians visit and relate with us more often, we will be able to improve our language skills.”

- When did you find out that the Hamshens have Armenian roots?

- I always knew. Even fifty years ago. Sure, we learnt about it in secret, but we knew. We just couldn’t openly declare that our language was Armenian.

- Why?

- At the very least, anyone who said they had Armenian roots was thrown in jail.

Was there ever an incident when a Hamshen was arrested just for saying that he/she was of Armenian extraction? No one wanted to risk an answer. Harun spoke of an incident in 1982 when an ASALA activist had been arrested. They showed him on TV and the guy spoke a few words in Armenian. In an open-air cafe a Hamshen named Tahsin Alper said, “Geez, the guy is one of us.” Alper was thrown in jail just for uttering the word “us”. Alper was a heavy drinker and died years ago.

(to be continued)

Khachatur Terteryan assisted in the research work.

Photos by Anahit Hayrapetyan

Translated by Hrant Gadarigian

[1] Translator’s Note: To simplify, the term “Hamshen” will be used both as an adjective {Hamshen Armenians, Hamshen Armenian dialect, as well as a noun {the Hamshens, Hopa-Hamshens etc. unless otherwise noted. The Hamshen Armenian dialect is commonly referred to as “Hamshesnak” or “Homshestma” in most academic texts.

[2] Ghevont, History (Yerevan: Sovetakan grogh,1982)

[3] Levon Khachikyan, Ejer hamshenahye patmutyunic (“Works” Vol. 2)

[4] Hovhan Mamikonyan, Taroni patmutyun ( Yerevan: Sovetakan grogh, 1989)

[5] Ibid. Vardan Vardanyan’s preface

[6] Levon Khachikyan’s work was published several times, including, Hay azgagrutyun yev banahuysutyun, Vol 13 (Yerevan: Academy of Sciences, 1981) I have used Ashkhatutyunner, Vol, 2, 1999, as the final version.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “The Hemshin: History, society, and identity in the Highlands of Northeast Turkey”, Edited by Hovann H. Simonian (Routledge, London and New York, 2007)

[10] Sargis Haykuni, ‘Nshkharner: Korats u Mo˝ats‘uats Hayer’ [Fragments: Lost and Forgotten Armenians], Ararat (Vagharshapat, 1895),

[11] Levon Khachikyan, Ejer hamshenahye patmutyunic (“Works” Vol. 2, Gandzasar Theological Center, Yerevan, 1999)

[12] Ibid

[13]Cemil Aksu, Hopa researcher, gave me the entire dissertation thesis

[14] “The Hemshin: History, society, and identity in the Highlands of Northeast Turkey”, Edited by Hovann H. Simonian (Routledge, London and New York, 2007)

[15] Lusine Sahakyan, “Frequently fraudulent and exaggerated statistics regarding the numbers of Hamshentsi are circulated” (Asbarez; June 8, 2011)

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (14)

Write a comment