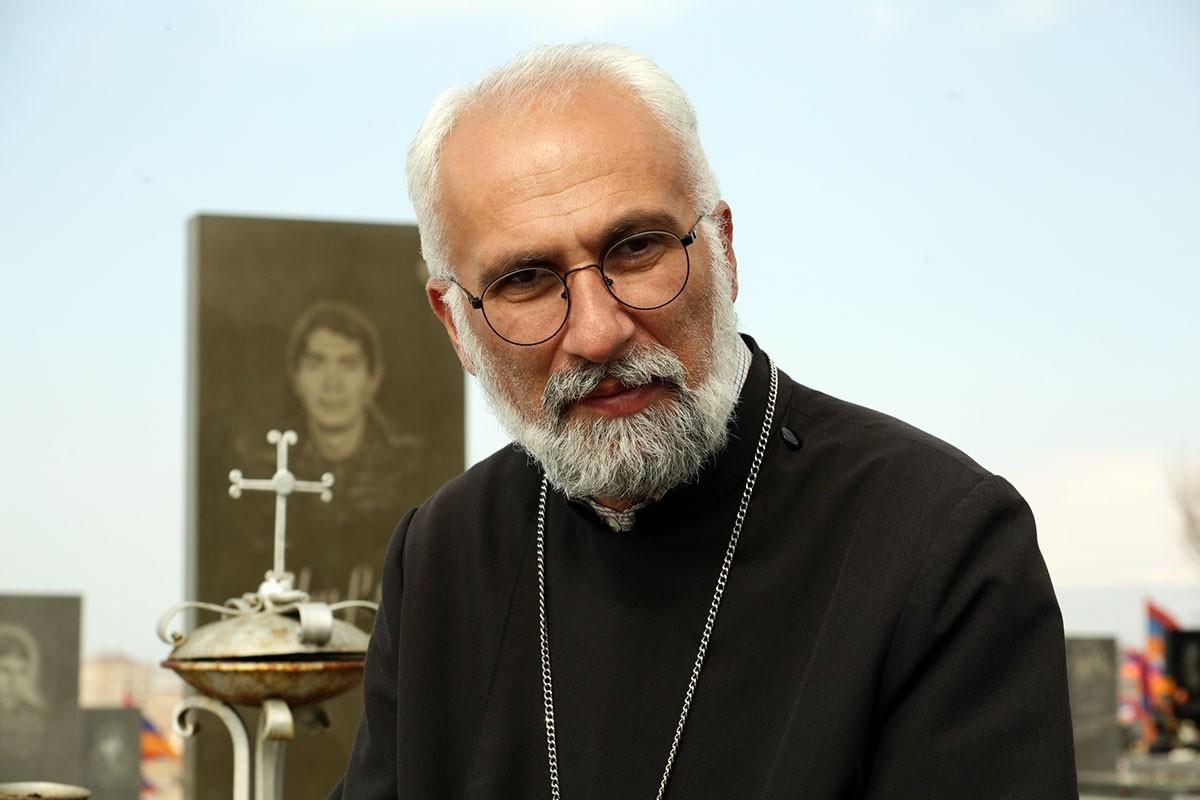

Father Psak’s Solitary Burden: Armenian Army Chaplain Performs Burial Services for Karabakh War Dead

Father Psak Mkrtchyan says he’s seen the face of hell.

He’s one of the clergymen performing burial ceremonies at Yerevan’s Yerablur Military Pantheon for Armenian combattants killed during last year’s Karabakh war.

”I am often asked if hell is a tangible reality. I say yes, I have seen it, because what we saw during the 44-day war can only be compared to hell, when the sound of mourning just deafens your ear. You cannot tolerate it. But I think that God imparts strength so that we can also offer a little consolation to our families with our prayers,” says Father Psak Mkrtchyan, an army chaplain.

At Yerablur, Father Psak and I sit next to one of the graves. There’s a field of Armenian tricolor flags all around. The flags fly from all the new graves, numbering more than 700. The smell of incense and the sound of mourning merge. A cold wind blows the flags. I feel the weight of an unfathomable sadness.

September 27 was the Feast Day of the Holy Cross of Varag Monastery. Father Psak was performing a mass that day at one of the army units when he heard that war had broken out in Karabakh. He says he can’t recall much about the church service. Many in the congregation rushed to their units after the mass concluded. Some went to the front, others stayed in rear-line positions.

The first war victim was buried at Yerablur three days later. Father Psak has been conducting burial services here since October. Other clergymen assist him when the number to be laid to rear is high. The first days of the war were difficult. There were times when eighteen victims were buried in one day.

"It was a heavy emotional situation because what we saw was a crazy, insane phenomenon. It started with daily burials, from 10-11 in the morning to 6-7 in the evening. We buried our boys with prayer, with the desire and hope that God would make their souls one with His light, with His kingdom, because they are soldiers of light who are the most precious. They gave their lives for the defense of the homeland," says Father Psak.

Ours is an uneasy conversation. Questions seem superfluous. I look at an elderly couple walking by. The woman holds a bunch of red tulips, the husband, a large tricolor flag.

"What happens at funerals is simply quite difficult to describe in words. What can you say to a parent who’s lost a child? Saying their son is a hero brings no comfort. You just keep quiet and keep praying," says the army chaplain, his voice breaking up.

"How did you manage physically?" I ask him.

“I wonder how we managed. Maybe God gave us strength. Now that I look back, I do not know. I have no other explanation other than faith and God,” Father Psak responds.

“Are there any scenes that remain with you?”

“There is a scene that I’ll never forget. It’s of a mother, who lost her son, dancing in front of the church, in the square. She just danced, saying that she did not have time to marry off her child, to see him happy. I try not to remember such things.”

The daily grind of Yerevan, in the distance, seems insignificant from the vantage point of the Yerablur cemetery. Cars and pedestrians rush here and there, seemingly out of time.

“Time stands still in Yerablur. There is no past, no future. Only the present exists, and you are in this reality. A reality in which all these boys are alive. Perhaps that is the consolation," says Father Psak.

The army chaplain says the reality of Yerablur must impact the lives of people who never need to visit it.

“It’s a place to learn, a place to be cleansed. It’s a place for people to come and reevaluate their lives, to make sense of living. Otherwise, you cannot enter and stay long. The place will oppress you and you’ll have to run away. But when you enter in a state of mind that is appropriate for this sanctuary, you involuntarily assimilate into the environment, you involuntarily walk with these boys, you listen to them. You say a prayer.”

“What do they say?” I ask.

“I believe that everyone now seeks something so that we can live on and be strong. So that we do not deny the important mission they undertook and carried out at the cost of their lives.”

“Do you carry this burden when you go home?”

“To be honest, yes. When you see this multitude of boys, who are no longer physically with us, who will not take their place in society, you grieve for the mothers who visit here every day, for the fathers who silently express their pain, carrying it within them.”

Our conversation ends. Father Psak prepares for another burial. The bodies of two conscript soldiers are to arrive.

Father Psak confesses that while it’s his duty, as a clergyman, to perform such services, each new burial affects him as if it were his first.

Father Psak, according to church tradition, also visits the homes of those who lost sons in the war. He’s says the pain they feel will never fully abate. He says that if God is present in their lives, their anguish may lighten, but fully accepting the reality of their loss is impossible.

"This is not the pain of one individual, one family. We all share it. If a person comprehends the reality, then he must experience pain, great pain. But we must not despair. We must fight, because to despair means to betray those boys. They certainly did not go forward with those thoughts. They did not die with those thoughts. They were loftier, brighter. Yes, suffering will be with us for the rest of our lives, but it should not cause despair, skepticism or retreat,” says Father Psak.

We take a walk through Yerablur. The number of graves increases daily. New holes are dug. It seems they are being dug in our souls.

Father Psak shows me the grave of one of the boys. The chaplain says he sent him off to the army from Yerevan’s Kanaker church. A year later, he performed the soldier’s funeral.

The priest stands by the grave, silently gazing at it for several minutes.

Photos by Hakob Poghosyan; Video by Ani Sargsyan

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment