Russian Relokants in Yerevan: Has Relocation Meant Integration?

Martha Gathercole

“The first thing I really remember about Armenia is that people are open, they approach you and chat to you.” Yulia, a Russian relokant living in Yerevan, tells me, reflecting fondly on how her love for Armenia has grown over her last three years here.

Yulia came here from Moscow in 2022 following Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, with her Armenian husband and five daughters. Originally intending to move to Georgia, they were rejected at the border and had to make a stressful snap decision to move to Yerevan. Despite this, she tells me how she is enjoying the comparatively relaxed atmosphere of Yerevan, compared to her life as a Russian teacher in the high-speed buzz of Moscow.

She shares more about her five daughters, and her concerns that she had for them settling into a new place. The younger three have been to Armenian schools and have picked up Armenian. However, she shares her concern for the integration of her eldest daughter into Armenian society, studying remotely at an online Russian school. “Because she's older, it wasn't easy for her to integrate into a different language environment. It was a language that none of us knew. It was very complicated, I saw some opposition and resistance to this, but gradually she is starting to integrate.”

Yulia with her daughters

A year ago, Yulia launched YerevanForKids, an initiative for restoring and building children's playgrounds throughout Armenia that are safe and sociable. She recounts the difficulty she faced persuading the Armenian mayors to allow her to raise money for this initiative. She shares how one mayor in Hrazdan refused to allow this, because it was suspected that this was a ruse to make money. Met with resistance in this Hrazdan, she has taken the initiative elsewhere.

Following the full scale invasion of Ukraine, 110,000 citizens of the Russian Federation came to live in Armenia in 2022, according to Vahan Kerobyan, former Minister of Economy for Armenia, and plenty more have come since then. Yulia is one of the many Russians who has had to navigate the challenges of education, language and socialising in a new country, with the added complexities of having a large family with mixed ages. Hetq conducted interviews with a range of Russians who have moved here and established a life here, to explore how far they have integrated into society, and how long they plan to stay here.

These migrants often call themselves relokants. Interviewees, however, had varied definitions of the term. Some specified that it is someone who has moved to a new place by choice, some say, somewhat inversely, that it refers to someone who has been moved with their company to another country without much choice. Some simply believe it is someone who moves temporarily, intending to return to their homeland, even if when this will happen is unknown. There seem to be as many definitions of relokant as there are relokants here in Yerevan, with lots of definitions seeming to overlap with terms like 'refugee' and 'migrant', terms which none of the interviewees used.

Perceptions of Armenia

Numerous interviews with Russian relokants revealed that their experiences of life in Yerevan have been, from their perspective, positive. However, these impressions reveal what they expected from Armenia, and how this has matched reality. Overall, their positive view of Armenia is thanks to the safety they feel here compared with Russian cities and the friendliness of people, who are, according to many Russians, always happy and smiling, with one mentioning that their parties are very loud. Interviewees found Armenia to be more hospitable not only than Russia, but also Georgia. Those who had moved to Georgia before living in Armenia described the experience of being pushed out, either by hostility faced when living there, or by outright refusal at the border, as was the case for Yulia's family.

Many interviewees confessed to knowing little about Armenia before coming here, with a few saying that all they knew was that it was a former Soviet state, a place on the map.

Many relokants left Russia very quickly and at short notice and so did not have time to research or form any expectations. However, they did have some implicit expectations. Many have expressed surprise at the number of good quality events that take place , one saying: “I am surprised at the number of fashionable places here, surprised that they're fashionable? No, just surprised that the venues are so varied, that they're not afraid of that”.

The common theme among these interviews was that Russian relokants have been very well received in Armenia. One expressed that this was surprising given Russia's lack of support for Armenia in the Artsakh wars, saying: “I would have thought because of the political situation, that Armenians would not have related well towards us…I can't understand why we are treated so well”. However, generally relokants did not consider Armenians’ kindness and hospitality towards Russians in spite of Russia's actions in Artsakh to be surprising. In fact only two interviewees mentioned Artsakh at all.

Social lives

From 2022 to the first half of 2025, 2,681 Russian citizens applied for Armenian citizenship, and 2,336 received it. Notably, the number of applications received in 2022 (581) was about eleven times higher than the number of applications in 2021 (52). In addition to Russians, this figure may include other nationalities who are citizens of the Russian Federation, excluding Armenians.

In social circles, Russians, for the most part, have exclusively Russian friends according to interviewees. Russians who had Armenian spouses naturally had more Armenian friends, but many have moved from Russia with friends and have remained in those circles. Others have met other relokants online, through social events or simply through Telegram groups and Instagram. Those with children recount how they have met many friends through the Russian schools which they have sent their children to. The general consensus among interviewees is that Armenians are friendly, but that they wouldn't say that they have Armenian friends.

Interviewees, especially those from Moscow, have been pleasantly surprised by the ease of moving around Yerevan. They say they can meet friends far more spontaneously and more frequently than in big Russian cities. Almost all those asked have noticed that there are far more social events in Yerevan now than when they first arrived. However, despite the apparently more active social lives of Russians here than in Moscow, their social circles still appear to be unanimously Russian.

It seems like Yulia's initiative has been a rare and valuable way that Russians and Armenians have been able to form friendships through a shared goal, after all, as she puts it: “regardless of differences, all children need somewhere to play”.

Yulia’s team, a mix of Armenians and Russian relokants collaborating on a YerevanForKids project

Working lives

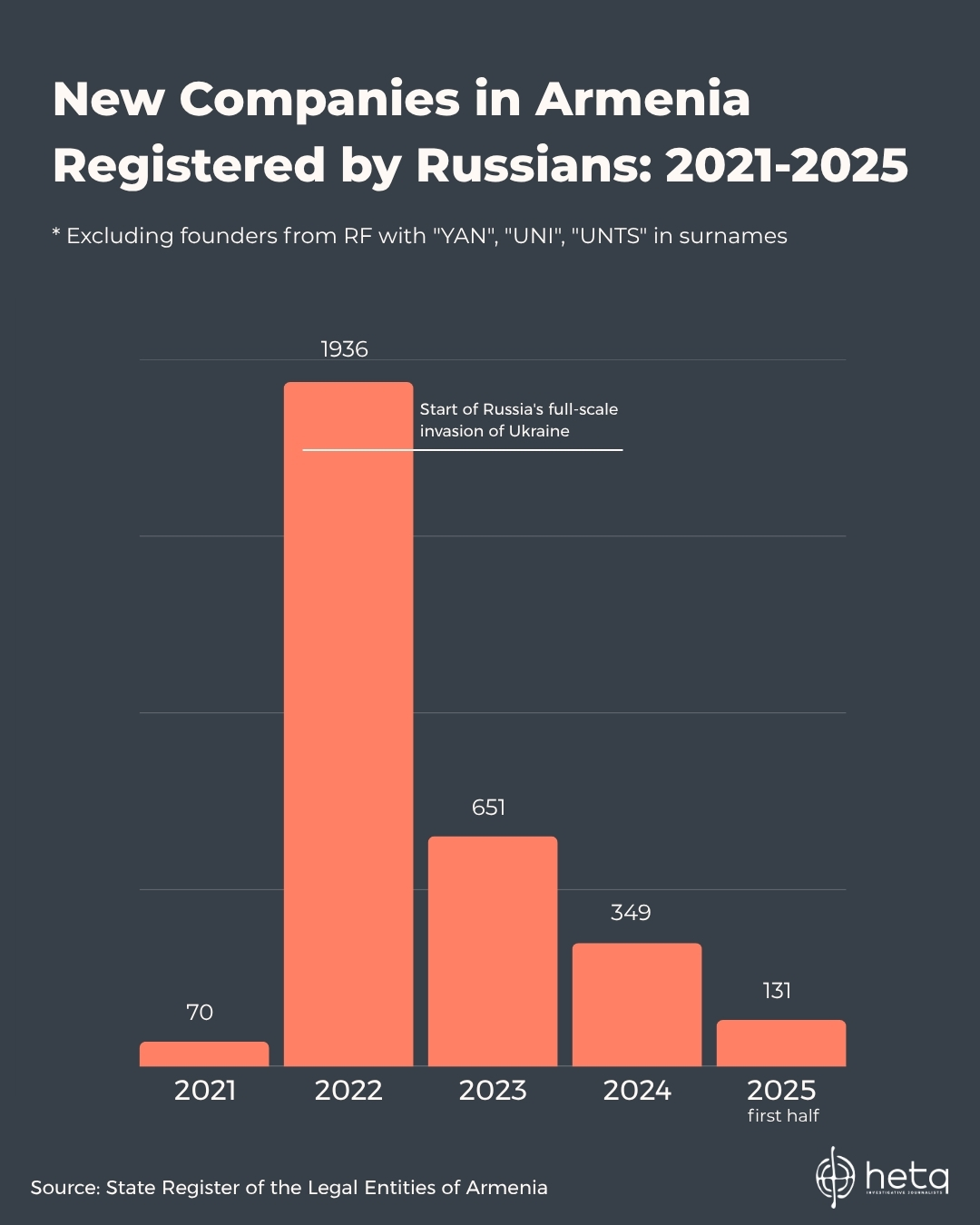

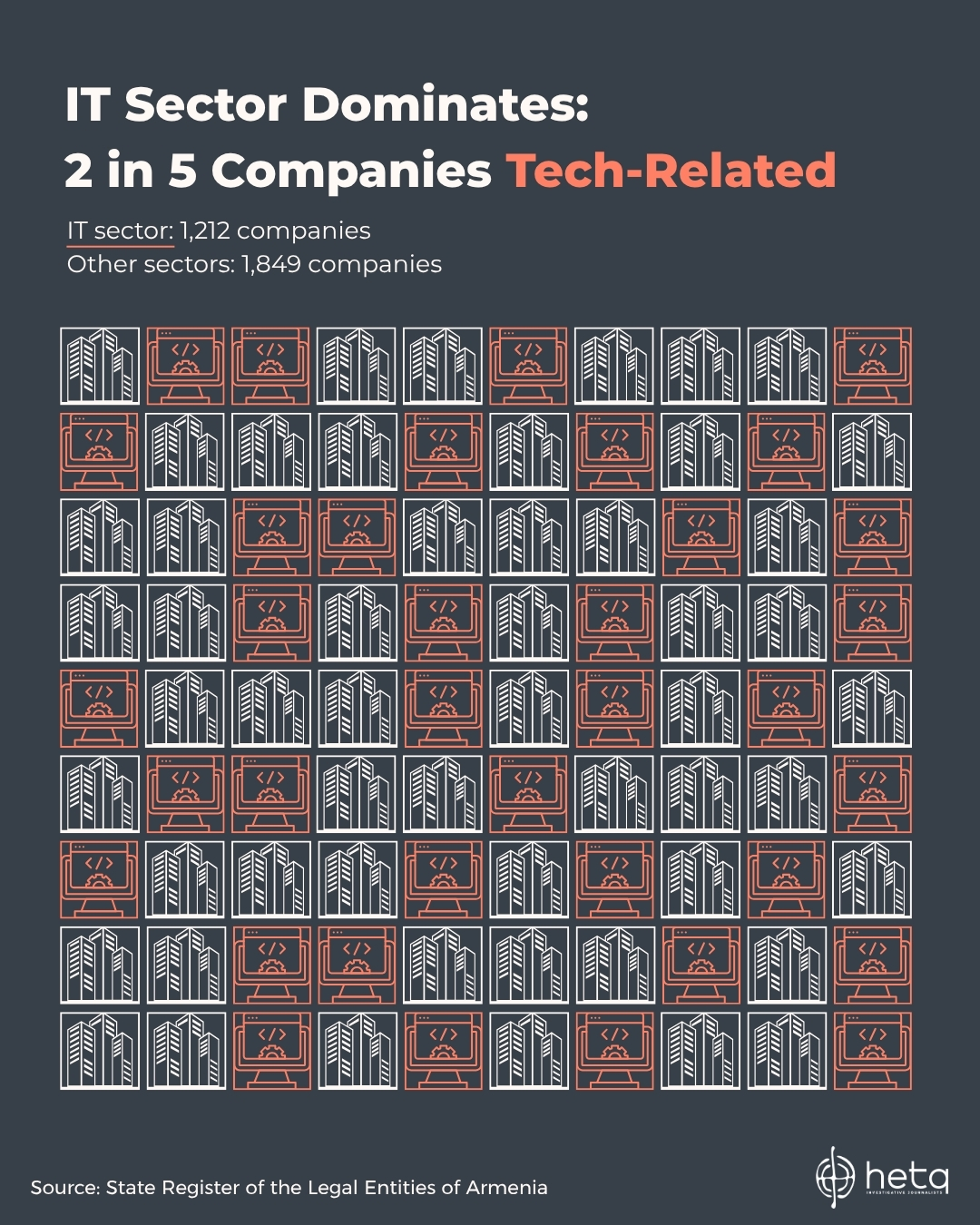

After the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, many Russians relocated to work remotely from other countries, with Armenia being one of the most popular destinations. Many also registered their companies here. Since the start of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russians have registered over 3,000 companies in Armenia according to the State Register of Legal Entities of Armenia. From this list, companies founded by Russian citizens with surnames typically associated with Armenians (ending in "-yan," "-uni," or "-unts") were excluded. An additional 900 companies were registered by ethnic Armenians who are citizens of Russia.

Interestingly, out of the total of 3,061 registered companies, 1,212 (almost 40%) operate in the IT sector. This means that roughly two out of every five companies are tech-related. Software Development is the dominant category, accounting for a massive 1,069 companies.

Besides the booming tech sector, Russians are also starting a variety of other businesses in Armenia. The most popular non-IT sectors include non-specialized wholesale trade (336 companies), general retail trade (257 companies), and business and management consulting (64 companies).

Almost 100 companies have been dissolved.

Interviewees also recounted their adjustment to a different working life in Yerevan. All of them work online either for Russian companies or international ones. Often coming from the busy high-speed environments in Moscow, they have found the approach to work here comparatively relaxed. One even commented that they believe Armenians to be “in a constant Spanish siesta”.

However, these Russians interviewed do not in fact work directly alongside Armenians in their online, internationally based jobs. It raises the question: are Russian relokants living in a bubble apart from Yerevan society, and forming incorrect perceptions of them as a result? Are the relokants in a bubble floating separately from Armenian society, meanwhile believing Armenians to simply be in a "constant siesta"?

Education for children

Schooling is another area where we see Russian relokants' extent of integration. Again, many with Armenian spouses have sent children to Armenian schools and kindergartens, since for them assimilation into an Armenian speaking environment is of course easier.

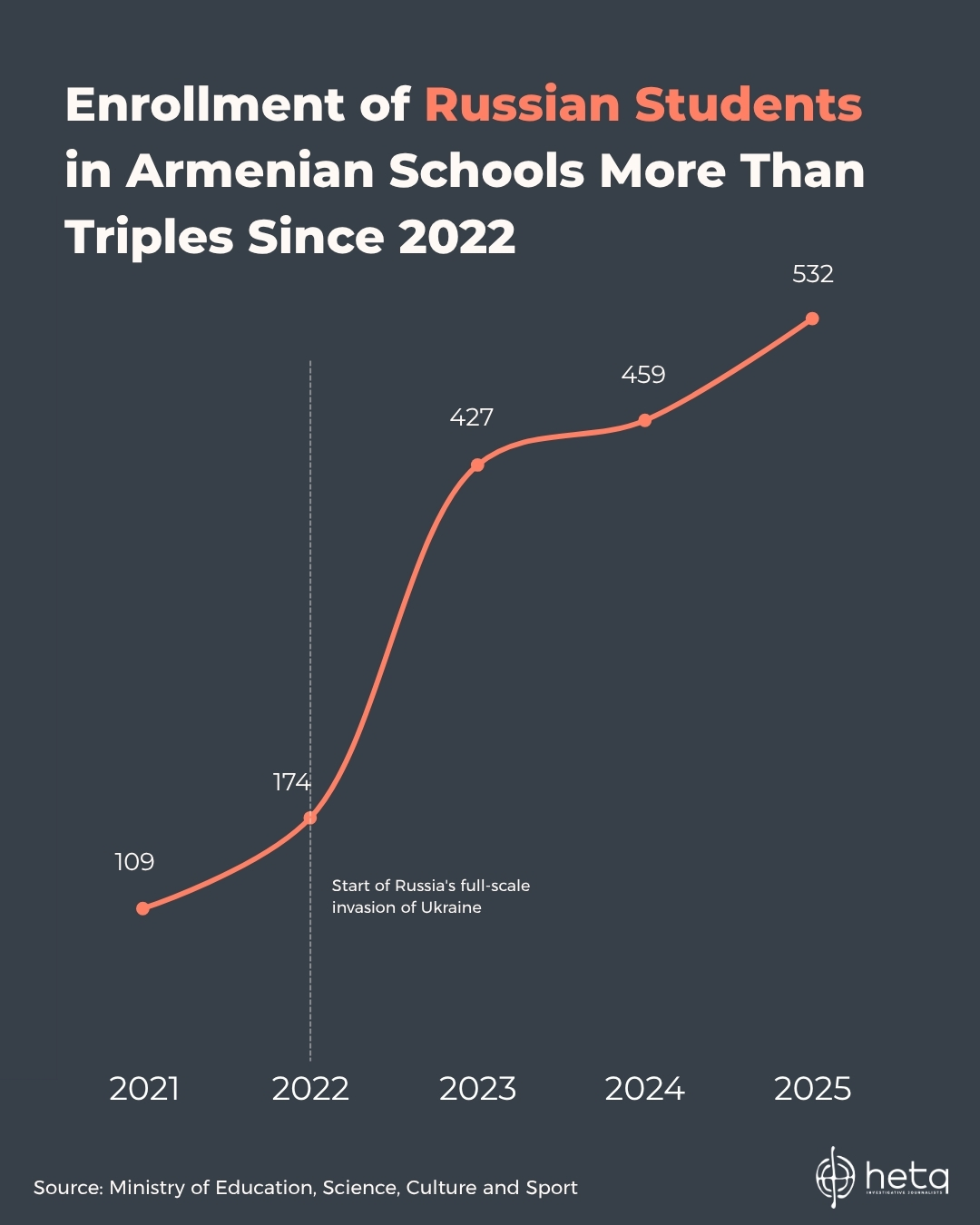

Between 2022 and 2023, the number of Russian students in Armenian schools more than doubled, increasing from 174 to 427. While the rate of growth slowed in 2024 and 2025, the number of students continued to rise steadily, reaching 532 by 2025.

In 2025, 395 Russian children enrolled in kindergartens in Armenia, and 77 Russian students have joined universities here.

Some families have chosen Armenian state schools where there is the option for education provided in Russian. The schools are predominantly Armenian speaking, but have separate groups for native Russian speakers. Their education is conducted in Russian but Armenian is an essential second language. According to the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sport website, there are fifty such schools across Armenia, forty six of which are state and four are private. Half of these schools are located in the capital.

Some parents have chosen private Russian schools for their children, where Armenian is not essential, but is taught as an optional extra subject. One parent admitted that their child, because they aatend this type of school, is “not integrating” into Armenian society.

And as Yulia reflects, it is even harder for her eldest daughters who continue to attend online Russian school to feel at home in Armenia.

Language

Overall, relokants have no problem speaking Russian in Armenia, and when unable to use Russian, are able to use English. A few have started learning Armenian, but have found it hard to both learn and practice given Armenians' readiness to engage in Russian. Many tell of how they started learning Armenian, but have lost motivation. Various initiatives have also been launched in Russian, such as SavetreesYerevan. According to its founder, there has been some complaint that the communication has been in Russian rather than Armenian. However, the founder said that this is simply information for a different audience, that there is no problem with initiatives in Armenia primarily communicating in Russian. They explain that there are similar initiatives in the city aimed at an Armenian speaking audience. Yulia's initiative, thanks to her learning Armenian, has been an exemplary way to merge Russian speaking and Armenian communities with the common goal of providing urban green spaces for the next generation.

Yulia has started learning Armenian and impressively uses it both spoken and in captions on the social media page for her initiative YerevanforKids. Not only has this brought together Russian relokants and local Armenians, but learning Armenian has given her more confidence and cultural understanding. When she moved here, her circle was limited to those she came from Russia with, but with the initiative, she began to meet Armenian officials, and mayors, and families wishing to collaborate in her projects. "Learning the language has meant I have been able to uncover the culture and history, because the language preserves all of this," she says.

Return to Russia

Is the relokants’ general lack of immersion into society a bad thing, if they are only in Armenia temporarily? Many say that they would return to Russia if the political system were to change. However, most stress that this would be a slow process, and so their return would not be quick.

Many relokants speak of friends who had moved with them to Yerevan, but simply used it as a ‘starting point’ before moving on to Europe. One recounted how some moved away because of how prices in Yerevan have gone up. When I asked why these prices had gone up, they said that this was probably because of the relokants themselves.

Indeed, the average rent for a studio apartment in Yerevan in February 2022 was 88,000 AMD per month (231 USD). By November 2022, this had already almost doubled to 160,000 per month (420 USD). This demonstrates that the full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent influx of Russian relokants had a clear correlation with increased rent prices. However, the influx of relokants also correlates to economic growth at that time: between January and July of 2022, Armenia's economic activity index grew by 13.1% compared to the same period of the previous year. In an interview with Hetq, former Deputy Prime Minister of Armenia Vache Gabrielyan noted that even without the Russian influx, there would have been economic growth, but not double-digit growth. "In my opinion, the double-digit growth is unambiguously linked to the Russian factor," he said.

Conclusion

As a result, Russian relocants, at least those with no family connections to Armenia, have largely not integrated into Yerevan society. But, as they emphasize, this is a temporary living situation. Many stressed that if they knew they would be living here permanently, their approach to life here would have been different, for example by learning the language.

However, perhaps living separately from society does lead to misconceptions such as Armenians living 'in an eternal siesta' and being constantly happy, whereas integration, as it did for Yulia, would open up more intercultural dialogues and understanding of the history. Russians confessed to knowing little about Armenia before coming here, but spending time uniquely in Russian communities reveals that perhaps they know little more than they did before, with so few mentioning the Artsakh war. They see Armenians as sociable and hospitable, but few elaborated what they are like beyond this in real life friendships, as so few have Armenian friends. The tolerance of Russian language, the ease of finding Russian communities online and remote work has allowed relokants to float above society and not integrate.

Yulia's story, however, is a beautiful example of integration into Armenian society. Through the initiative, she has now successfully been granted a space to build a playground in Stepanavan. This has already brought relokants and local Armenians together in collaborative initiatives, and will continue to do so if the project can receive enough funding to be realised.

The site where the park will be constructed, if the initiative can gather enough funding, and the plan for the finished park

Yulia has offered an example of how communities can be integrated, in this case by creating outdoor spaces that bring people of all ages together in towns throughout Armenia.

Top photo: Yulia with her five daughters

Photos from Yulia's personal archive

Data analysis and infographics: Nare Petrosyan

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (1)

Write a comment