Photographer Ara Oshagan: “I carry my many-sided identity around like a suitcase”

I was scheduled to meet with Ara Oshagan in Yerevan’s Republic Square.

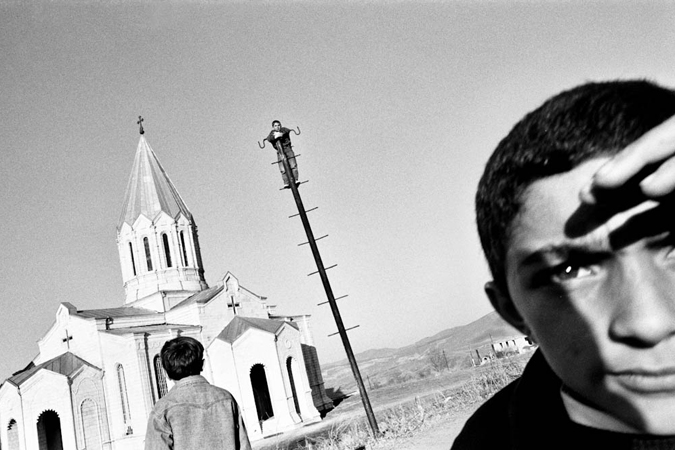

Ara Oshagan, son of writer and literary critic Vahe Oshagan, is a photographer born in Lebanon and now living in the States. He recently participated in Land & Technology, an art initiative that was part of the overall Shushi Art Project.

As I was waiting, I flipped through the photo book “Father Land”, co-authored by Ara and his father. The rainy weather prevented me from observing the quick moving photographer who was always on the look-out for the next great photo. With that same quickness we sat down at a cafe. In his hand was a piece of paper; a ticket to the National Painting Gallery. The bag slung over his shoulder and his appearance marked Ara as a consummate photographer more interested in connecting with his surroundings, individuals and objects. From the get-go Ara stressed...

“I am not a person of words. I have trouble talking. That which I will talk about already appears in my photos. I even can’t describe it all in just one photo. Also Shushi. There are two important things in a photo, attitude and series, so that what I have to say is complete. My photos are like sentences. When you compose correctly and well, you create a great novel that has the right start, middle and ending,” Ara says.

How did it come about that you, along with other artist, visited Shushi for the Shushi Art Project?

Harry Vorperian, the project director, decided who should be selected and he called me. He knew that I‘ve had a long relationship with Shushi dating back to the 1990s that essentially hasn’t changed. That emotional state has remained the same. It was an opportunity that would be hard to come by later on.

How did the idea come about for your installation, in which huge photos of Shushi residents were hung from the empty windows and doors of a ruined building? What’s the reason for such a project?

I always saw demolished buildings in Shushi that have large frames originally designed to hold large pieces of glass. These old buildings are something akin to witnesses of death and I thought about bringing at least one back to life.

What was the attitude of Shushi residents when you were taking photographs?

I started back in the summer. My aim was to portray Shushi residentsin images directed back to themselves. These photos show those who have resettled there; people of different ages and gender. The desire was the same, to see a hastened resettlement of Shushi.

One portion of the residents I was photographing was overjoyed and we even cemented close friendships. In this case, the concept of linking it to conceptual art was born. What was amazing was that many understood the meaning of the work. Others said it was to beautify the town.

There’s a girl in one of the photos who studies at the music school opposite the building. Every day she would bring her classmates and explain the meaning of the photos and would especially point out hers.

Do you think Shushi residents are ready to see the photos of relatives and friends instead of a building in ruins?

|

|

|

Shushi people are quite simple folk and I didn’t have the chance for complicated conversations. So I really can’t say what they felt deep down.

At the beginning, I had a problem choosing the type of photo. Then something interesting occurred. I entered the Ghazanchetsots Church and saw pictures of the apostles that were displayed from head to foot. This was a like a message for me and I decided to display the Shushi residents in the same manner. I ended up with gigantic photos that took up the entire empty alcoves of the building.

Please tell us a bit about when you were taking the photos.

It was a strange situation. Elections were taking place in Shushi when I started to photograph. The town was in a rush but we were slowing down. Many people didn’t want to see such large photos of themselves on a building. Naturally, I didn’t photograph those who declined.

What was also interesting was that relations began over a cup of tea or coffee that residents offered me. That’s when you get connected to their ordinary lives. You get a good sense of the situation. I had such contact for eight years and they were still a pleasant and interesting experience this time.

As an artist, how would you assess Shushi and the cultural developments happening there in general?

We got to meet several artists that were participating in general activities. I also saw construction which shows that progress is happening.

Our initiative is about conceptual art and it’s that art form that speaks about the future. You know, in this case, what is important is that while many residents might not have understood what was taking place, they are geared towards the future.

I would think that it’s pretty difficult to traverse the spatial and time difference and represent yourself with such art. Would you say that the identity issue comes to the fore in such a space?

For me, the identity issue is quite personal and singular. I am both Armenian and an American. There are times when I must feel myself totally American and the opposite, completely Armenian. This is the starting point for all my art. Those questions appear in my works. I am the person in my works.

When I take photos in Artsakh, I am photographing myself in that location, and that idea of several identities affords the artist great freedom. You become a resident of the world, carrying the influences of several cultures at once. It’s like being liberated. When the question of identity pops up I immediately take photos of myself and I see me.

You were in Artsakh in the 1990s with your father, Vahe Oshagan. You both wrote the book “Father Land” which also contains your photos of local residents and your father’s stories about the culture of Artsakh and the war. Back then, did the concept of situating the identity issue in photos also exist?

The photographic process is very important for me. The content isn’t focused but it is in that ambiguity that the person, the identity, of the photographer must come forth. The emotion of the photographer and being in that reality becomes more important than the content.

The book which I and my father made was the result of 15 years of collaboration. What’s amazing is that I lost my own father during that process and became a father myself and had four children. The book took shape in tandem with my life. I had a father, became a father and instilled a distinct explanation of identity in the work.

Wherever I go, that multi-faceted identity is with me, like my suitcase. You must constantly carry it around and always have a place for it.

See also Ara Oshagan / Kashatagh region. The village of Hakari. The family of Artash from Gyumri.

Ara Oshagan / Kashatagh region. The village of Haykazyan. The family of Pargev Hambaryan.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment