Armenians in the Ottoman Economy

Anahit Astoyan

Making Their Mark in Commerce and Manufacturing

Prior to WW I, Armenians played a pivotal role in various sectors of the Ottoman economy including foreign and domestic commerce, manufacturing, the banking sector, etc. The Turkish bourgeoisie, in comparison, found itself in a secondary role and oftentimes dependent role. The Young Turks feared that the further strengthening of the Armenian community, both economically and materially, would serve as the basis for their future political victories. Gradually, the Turkish ruling elite came to the belief that sooner or later Armenians would be in a position to take over the reins of political power, just as they had done in the economic sphere.

The organizers of the Armenian Genocide, besides pursuing political ambitions, also wanted to free themselves from competing with Armenians. By cleansing the Ottoman Empire of Armenians, the Young Turks also removed their most powerful economic competition, their property and, through the expropriation of Armenian wealth, they were able to cover a large part of their war expenses as well. The Young Turks, in a word, due to the wealth stolen from Armenians, were able to pay off much of the foreign debt threatening the newly independent Turkish republic. A Turkish bourgeoisie would soon rise on the centuries-old property and wealth accumulated by Armenians.

Let’s now take a brief look at the Ottoman economic sectors where Armenians played a significant role:

The selection process for Ottoman government officials took into account a candidate’s national and religious identity rather than competence and personal values. The vast majority of the bureaucracy, the police, military and court system were comprised of Muslims, largely Ottoman Turks. Taking mastery over the ruling governmental functions, they left the economy mostly to non-Turkish elements. Ottoman Turks hadn’t yet bvreacged that level of sophistication where they could manage and develop the empire’s economy and thus they were obliged to rely upon the experience of their non-Turkish subjects. Armenians, as the representatives of one of the oldest civilizations in the Near East, along with other subject people, strove for five years to keep the Ottoman economy flourishing. Deprived of the right to participate in administrative and military activities, commerce and crafts were the fields that became more or less the sectors where Armenians could manifest their skills and inherent competence.

The Ottoman sultans would quickly populate the cities they conquered with Armenians. In 1453, after seizing Constantinople, Sultan Muhammed ordered Armenian craftsmen and traders to the ravished capital to rebuild and turn it into a showpiece of the empire.

Armenian merchants reach out to Iran, India and beyond

Starting in the 15th century, the shops of Armenian traders began to flourish in Constantinople. Commerce between the Mediterranean and Black Seas to Iran and India beyond was largely in the hands of Armenian merchants. From the other prime Ottoman trading port of Smyrna, Armenians were in contact with the nations of Europe. From here, Armenian caravans made their way to Persia and other Asian countries. The custom taxes paid by Armenian merchants were one of the large sources of revenue for the Ottoman government coffers. From the 16th to 19th centuries, Armenian merchants played a major role in the development of Ottoman commerce and facilitated the transportation of Ottoman goods to Europe and Asia.

From the 16th century onwards, the Armenian amira and “chelepi” class (“chelebi” meaning ‘godly’ in Turkish). Like the “amiras”, they were wealthy merchants with close ties to government circles and high civil servants whose affairs they managed. These titles of honor were given to enterprising entrepreneurs from the regions that relocated to the capital, obtaining authority and influence. These Armenian amiras and chelebis soon worked their way into the inner sanctum of the empire’s ruling elite, a closed world to Christians. In the 18th century, these prominent individuals began to manage many important government departments and posts.

Amiras and Chelebis: Wealthy merchants with government ties

The Tiuzian family held a unique place in art and jewelery making and over the generations became the royal goldsmiths. The management of the mint and gold and silver reserves was confided to them. The Demirjibashian family ran the empire’s shipbuilding and cannon-making facilities. For generations, the Dadian family oversaw the outfitting of the military and arms and paper manufacture. Silk production and custom fee collection was the purview of Mgrditch Amira Jezayirlian.

After the Crimean War in the mid 19th century, when the Ottoman Empire opened its doors to the West, Armenians were ready to play a major role between the empire and Europe. Armenian merchants were fluent in the languages and customs of the Europeans. Many Armenian merchants, not satisfied with the selection of goods offered by the Europeans, established direct links with European manufacturers and commercial associations. Many Armenian merchants actually set up shop in various European cities and branched out beyond the narrow confines of Ottoman trade.

After the Crimean War in the mid 19th century, when the Ottoman Empire opened its doors to the West, Armenians were ready to play a major role between the empire and Europe. Armenian merchants were fluent in the languages and customs of the Europeans. Many Armenian merchants, not satisfied with the selection of goods offered by the Europeans, established direct links with European manufacturers and commercial associations. Many Armenian merchants actually set up shop in various European cities and branched out beyond the narrow confines of Ottoman trade.

By the 1850’s, large numbers of Armenian merchants were making their way to Constantinople Smyrna and other coastal towns from the interior regions. This further strengthened the position of Armenians in the Ottoman economy. Armenian commercial houses in the capital and Smyrna became institutions unto themselves. With the introduction of European capital and manufacturing, the economic condition of Armenians quickly improved. In 1908, “Hay Bankan”, a branch of the Ottoman Bank to be managed by Armenians was established and greatly facilitated Armenian commercial transactions.

However, this Armenian economic development took place under the arbitrary conditions rampant in the Ottoman Empire. For instance, Turkish merchants with similar revenues were charged three times less in taxes than their Armenian counterparts. Plunder and deliberate arson had taken their toll on the markets in Van, Adana, Kharpert and elsewhere. In 1908, the Ottoman authorities seized Armenian manufacturing centers in the town of Kharpert.

However, this Armenian economic development took place under the arbitrary conditions rampant in the Ottoman Empire. For instance, Turkish merchants with similar revenues were charged three times less in taxes than their Armenian counterparts. Plunder and deliberate arson had taken their toll on the markets in Van, Adana, Kharpert and elsewhere. In 1908, the Ottoman authorities seized Armenian manufacturing centers in the town of Kharpert.

Despite these trials and tribulations, Armenians continued to play a leading role in Ottoman trade and commerce.

The following statistics, culled from the Armenian State Archives by historian John Giragosian, give a picture of the economic state of Armenians prior to WW I.

In the villayet of Sivas (Sebastia), 141 out of 166 commercial importers and 127 out of 150 importers were Armenian. Out of the 9,800 small traders and craftsmen, 6,800 were Armenian.

Alexander Myasnikyan, in a lecture he presented in Moscow in 1913, noted that despite the fact that Armenians comprise 35% of the population in the villayet of Sivas, they make-up 85% of the traders, 70% of the craftsmen and 80% of the manufacturing houses.

The drive and initiative of Armenians wasn’t only confined to trade and commerce. They proved their mettle in all economic sectors. There were also Armenian merchants who transported European machinery and parts back to the empire and started to produce goods with European quality and appearance.

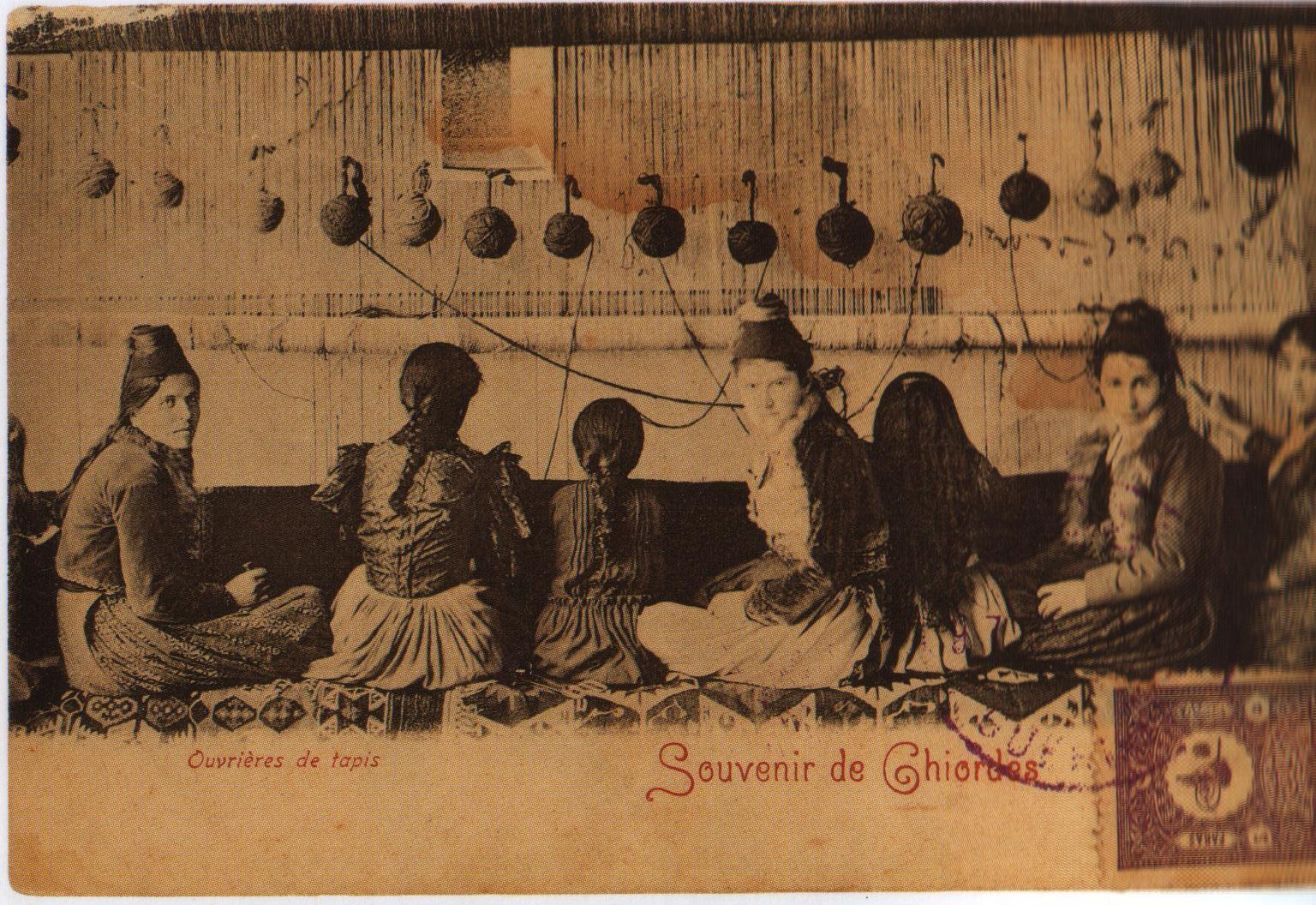

Armenian manufacturing prior to the Genocide

Gradually, the nature of capital in the Ottoman Empire began to change from commercial to manufacturing capital. In Arabkir, at the beginning of the 20th century, where Armenians were mostly engaged in linen production, there were already scores of manufacturers focused on specific linen products; sheets, tablecloths, intricate weaves, etc. The woolen items and copper pieces produced in the towns of Garin, Van and Baghesh were sold locally as well as overseas. Of the 150 manufacturing units in operation in the villayet of Sivas at the time, 130 belonged to Armenians; the rest in Turkish or foreign hands. Out of the 17,000 production workers, some 14,000 were Armenians.

One must remember that the Turks remained loathe to enter commerce and the crafts, believing those professions to be beneath them. Overwhelmingly, they aspired to the loftier heights of government and military appointments, leaving Ottoman subject peoples the task of creating conditions for the economic prosperity of the empire.

In his memoirs, Sultan Abdul Hamid II (the Red Sultan) wrote, “The source of all our evils is that the Ottoman doesn’t strive to create any actual value. He is accustomed to become a ‘baron’ and to leave the real work to others. He lives to enjoy life. Our youth believe that they cannot become anything other than an officer or official.”

To be continued

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment