Armenians in the Ottoman Economy – Part 2

Anahit Astoyan

When touching upon Armenian artisans in the Ottoman Empire one must naturally begin by recounting the contributions made by Armenian architects – masters of construction – those who worked brick and stone to create many of the edifices that can still be seen today in Istanbul and elsewhere. For centuries, these craftsmen contributed to many of the construction works and projects in the empire – public houses, palaces, mosques, etc.

Armenians built the important Haydar Pasha – Baghdad railway line. For successive generations, oversight of State construction works, i.e. royal architecture, was the domain of the Balian family. For two centuries, nine members of this singular family served as the empire’s royal architects and decorated Constantinople with the impressive edifices; thus leaving their indelible mark on the capital of the sultans. Prior to the Balians, there was a long line of royal Armenian architects, starting from Sinan the Great, who played a significant role in the building of the empire.

The art of rug making was introduced and developed by the efforts of Armenians. The famous Venetian traveler Marco Polo commented that Armenian subjects of the Ottoman Empire weaved the most delicate and beautiful rugs of the day.

The art of rug making was introduced and developed by the efforts of Armenians. The famous Venetian traveler Marco Polo commented that Armenian subjects of the Ottoman Empire weaved the most delicate and beautiful rugs of the day.

In general, all the crafts that flourished in the Ottoman Empire, including rug making, have been attributed to Turkish sources in Europe. Now, however, no one is surprised by the fact that all those rugs known as hailing from Asia Minor are actually the work of Armenian weavers. Rug making was one of the preferred crafts of Armenians. Armenian rugs weaved in many of the empire’s towns and cities – Sepastia, Kesaria – were highly appreciated on the international market.

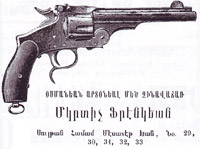

Armenian arms craftsmen were also held in high regard throughout the empire. Armenian arms manufacturers in Garin (Erzeroum) supplied the Ottoman Army with their wares for centuries. The Vemian family of Garin was noted as being one of the top armament makers. There were also many Armenian royal arms makers that supplied weapons for the sultans and the imperial court. Many of their works are now displayed in some of the most famous museums in the world.

Armenian arms craftsmen were also held in high regard throughout the empire. Armenian arms manufacturers in Garin (Erzeroum) supplied the Ottoman Army with their wares for centuries. The Vemian family of Garin was noted as being one of the top armament makers. There were also many Armenian royal arms makers that supplied weapons for the sultans and the imperial court. Many of their works are now displayed in some of the most famous museums in the world.

There were certain crafts that were solely the domain of Armenians – e.g. carpentry and furniture making. During the 1860’s, the Kemhajian family stood out as master furniture makers. Kalust Kemhajian was the first to open and operate a furniture plant in the Ottoman Empire. Many of his finely wrought pieces adorned the royal palaces of sultans and princes. The Kemhajian family was later joined by other Armenian master craftsmen who further developed the trade by establishing woodworking and furniture businesses of their own.

There were certain crafts that were solely the domain of Armenians – e.g. carpentry and furniture making. During the 1860’s, the Kemhajian family stood out as master furniture makers. Kalust Kemhajian was the first to open and operate a furniture plant in the Ottoman Empire. Many of his finely wrought pieces adorned the royal palaces of sultans and princes. The Kemhajian family was later joined by other Armenian master craftsmen who further developed the trade by establishing woodworking and furniture businesses of their own.

Kyutahia – Center of exquisite pottery

The art of pottery making in the empire started in Kyutahia by Armenians in the 15th century. Migrant Armenian artisans from Persia imparted a new style to the manufacture of glazed earthenware. 18th century Turkish historian Evlia Chelebi in his “Travelogue” notes that the residents of the three Armenian quarters in the town of Kyutahia are engaged in the manufacture of ceramics. Armenian craftsmen were able to make use of the innovations of Europe, especially France, and soon their wares were quite competitive on the European market. In 1914, the three Armenian ceramics works in Kyutahia were producing for the London and Paris markets. This craft was also to be found in other communities throughout the empire where Armenians from Persia had resettled. Pottery and ceramics made in Kyutahia are recognized worldwide as impeccable works of art and samples are on display in the world’s top museums.

The art of pottery making in the empire started in Kyutahia by Armenians in the 15th century. Migrant Armenian artisans from Persia imparted a new style to the manufacture of glazed earthenware. 18th century Turkish historian Evlia Chelebi in his “Travelogue” notes that the residents of the three Armenian quarters in the town of Kyutahia are engaged in the manufacture of ceramics. Armenian craftsmen were able to make use of the innovations of Europe, especially France, and soon their wares were quite competitive on the European market. In 1914, the three Armenian ceramics works in Kyutahia were producing for the London and Paris markets. This craft was also to be found in other communities throughout the empire where Armenians from Persia had resettled. Pottery and ceramics made in Kyutahia are recognized worldwide as impeccable works of art and samples are on display in the world’s top museums.

Armenian Jewelers

Armenian jewelers have been plying their trade for many centuries. Important jewelery centers were located in Constantinople, Van and Garin. Evlia Chelebi writes that the Armenian jewelers of Garin are to be considered the most skilled masters of the art in the world. From the 18th-19th centuries, Armenians dominated the ranks of jewelers in Constantinople. In an 1806 edict by the sultan, of the seventeen top jewelers noted, only one was a Greek; the others being all Armenians. The quality of the work produced by Armenian jewelers, goldsmiths and silversmiths surpassed that of Europe. Armenian goldsmiths were also accomplished craftsmen when it came to working with precious stones, especially diamonds. Armenians pioneered the art in the empire. Armenian diamond polishers, cutters and setters held their own against their counterparts in Holland, Belgium and France.

Armenians were also at the top in the field of watch making.

Armenians were also at the top in the field of watch making.

A prominent name in the field of watch making is that of the Kevork Tchouhadjian, the father of noted composer Dikran Tchouhadjian.

The father served as the royal watchmaker to Sultan Abdul Mejid during the mid-1860’s while the son founded the first opera institution in the Ottoman Empire.

Zildjian – Nearly 400 Years of Cymbal Making Excellence

The Zildjian family made top quality cymbals in the Ottoman Empire for nearly three centuries starting in 1623 when Avedis Zildjian, an alchemist, was looking for a way to turn base metal into gold.

He created an alloy combining tin, copper and silver into a sheet of metal that could make musical sounds without shattering. The sultan’s famed Janissary bands are quick to adopt Avedis’ cymbals for daily calls to prayer, religious feasts, royal weddings and the Ottoman army. Sultan Osman II acknowledges Avedis to be the founder of the craft of Turkish cymbal making and gives him the family name “Zildjian” (cymbal smith).

He created an alloy combining tin, copper and silver into a sheet of metal that could make musical sounds without shattering. The sultan’s famed Janissary bands are quick to adopt Avedis’ cymbals for daily calls to prayer, religious feasts, royal weddings and the Ottoman army. Sultan Osman II acknowledges Avedis to be the founder of the craft of Turkish cymbal making and gives him the family name “Zildjian” (cymbal smith).

By the 1860’s, Kerope Zildjian is exporting 1300 pairs of cymbals per year throughout Europe. During the mid to late 19th century, Berlioz and Wagner begin featuring cymbals in their compositions and request that only Zildjian cymbals be used. The Austrian composer Johann Strauss orders Zildjian cymbals and notes that they fill an important percussion gap in his orchestra. By 1914, the Zildjians have two production units; the original foundry in Samatya, a suburb of Constantinople, and a second in Bucharest, founded in the early 1900’s. The Zildjian family continues to produce cymbals in Massachusetts and is the preferred cymbal of choice by the world’s top orchestras and musicians. At nearly 400 year-old, Zildjian remains the world’s largest manufacturer of cymbals.

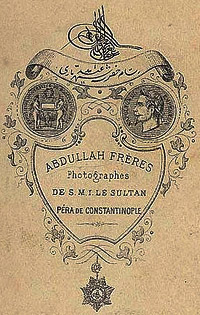

Photography – The Abdullah Frères

The Armenian brothers Viken, Hovsep and Kevork Abdullah pioneered photography in the Ottoman Empire and operated a famed photographic studio in Constantinople from 1858 to 1900. Known by their French name “Abdullah frères” (Abdullah brothers), they became official royal photographers to the Ottoman Sultan in 1863, and had the right to use the royal monogram. Between 1866 and 1895, they also had a branch studio in Cairo. They took portrait photos of many European luminaries visiting Constantinople including Edward, Prince of Wales, who visited in 1869 and Empress Eugenie of France. Of particular interest is that American author Mark Twain, during a visit to the Ottoman capital in 1867, was also photographed by the brothers.

The Armenian brothers Viken, Hovsep and Kevork Abdullah pioneered photography in the Ottoman Empire and operated a famed photographic studio in Constantinople from 1858 to 1900. Known by their French name “Abdullah frères” (Abdullah brothers), they became official royal photographers to the Ottoman Sultan in 1863, and had the right to use the royal monogram. Between 1866 and 1895, they also had a branch studio in Cairo. They took portrait photos of many European luminaries visiting Constantinople including Edward, Prince of Wales, who visited in 1869 and Empress Eugenie of France. Of particular interest is that American author Mark Twain, during a visit to the Ottoman capital in 1867, was also photographed by the brothers.

In the capital and major cities throughout the empire, Armenians dominated the legal professions, medicine, photography, pharmacy and other professions. According to the Russian historian Goloborodko, if it weren’t for Armenians in the empire’s urban centers there would be no arts, science, crafts or technical representation.

Agriculture and farming, especially in the eastern Anatolian villayets, with few exceptions, were in the hands of Armenians. Wine making, horticulture, bee-keeping, silkworm raising, etc., were developed by Armenians as well.

During the 19th century, Armenian specialists who had graduated from top agricultural colleges in Europe were the first to spread new farming methods througout the empire. Some of the more prominent Armenians in the field include Krikor Aghaton, Hagop Amasian and Aram Yeram. It was due to their efforts that agricultural and veterinarian institutes were opened in Constantinople and other cities.

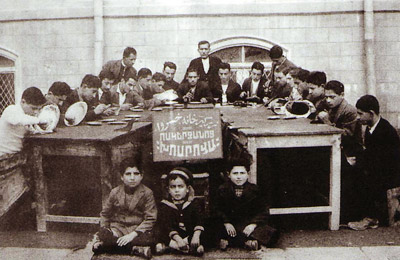

The raising of silkworms and silk manufacturing were two related agricultural fields that Armenians helped develop, given that they had early on noted their importance. At the beginning of the 19th century, Boghos Amira Bilezigjian and Hagop Chelebi Diuzian opened the first spinning mills in the city of Boursa. The silk articles produced in their mills were widely in demand both domestically and in Europe. It was another Armenian, Mgrditch Amira Jezayirlian, who modernized the silk manufacturing process, thus expanding the scope of the industry. The silk woven in his shops won top prizes at the London Exhibition of 1851. Silkworm cultivation reached new heights when in 1888 Kevork Torkomian opened a technical school focused on silkworm cultivation in Boursa. For the next 35 years, he serves as principle and faculty head.

In 1870, the Faprigatorian brothers opened a silk factory in Kharpert that was equipped with the latest in European machinery. Of its kind, it was unique throughout the country

Mikayel Pasha Portukalian and Hovhannes Pasha Sakuzian, viziers who managed the personal offers of Sultan Abdul Hamid II, were instrumental in implementing economic reforms in the empire. They were the first to create economic and political-economy faculties in the empire’s top schools.

The following depiction by Johannes Lepsius, an eyewitness to the 1915 Armenian Genocide, concisely assesses the position held by Armenians in the economic life of the Ottoman Empire – “After the deportations of Armenians, in the emptied out towns and cities left behind, with few exceptions, there are no longer any iron mongers, stone masons, carpenters, jewelers, tailors, potters, shoemakers, goldsmiths, pharmacists or lawyers. There was not one person left who was engaged in freelance professions or the trades.”

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment