In Armenia the Rich Rule: Liberal Democracy Is Plutocracy

By Markar Melkonian

A politician in Yerevan recently noted that, “if the oligarchs are omitted from the National Assembly, only one or two MP’s will remain, and the cabinet will be empty.”

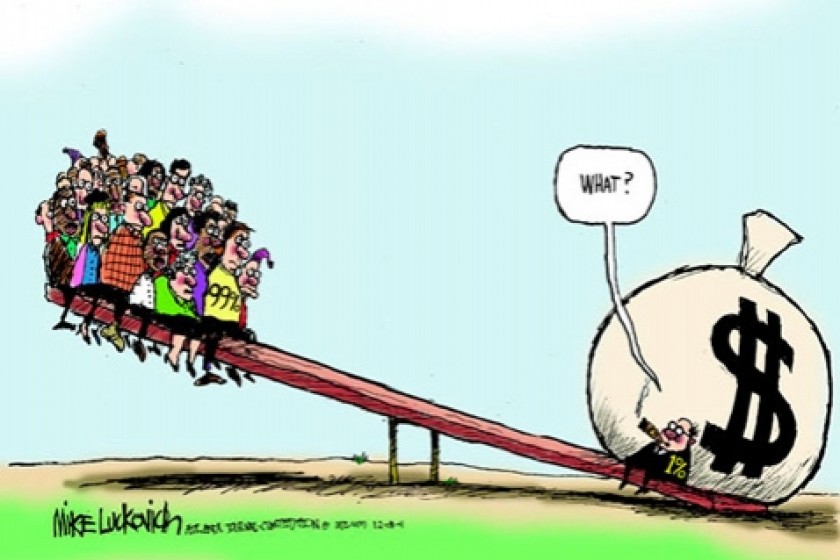

What is obviously true of the legislature is just as obviously true of the Presidency and the Ministries, the judiciary, and local and regional state agencies. In Armenia today, as in other capitalist democracies, the wealthiest few hold a near-total monopoly of political power.

But this all-too-evident truth flies in the face of the “mainstream political science” taught in places like the American University of Armenia.

One of the most influential American political philosophers of the last century, John Rawls, claimed that in a liberal democracy like the United States, “political power is the coercive power of free and equal citizens as a corporate body.” Perhaps it should count as an achievement that a liberal thinker has at least managed to acknowledge the essentially coercive character of political power. But in what sense are citizens of a state that is dominated by the super-wealthy few “equal” as a corporate body—let alone “free”?

The modern liberal state, we hear, is a level playing field upon which a wide range of multiple interest groups compete to influence the electorate. Mainstream political thinkers call this view of democratic politics Majoritarian Pluralism. According to their story, this is what the American political system is all about, and other liberal democracies, too. Bringing this kind of democracy to Armenia is the advertised aim of more than one of the one-man shops that go by the name of political parties in Yerevan these days.

But let us take a closer look at Majoritarian Pluralism. If it were right, then this would make a difference when it comes to how policy is made. It would have implications, for example, when it comes to what sets of actors have influence over public policy and how much influence they have. If Majoritarian Pluralism were genuine, then in liberal democracies, mass-based interest groups, such as large consumer advocacy organizations, grass-roots environmental movements, and popularly supported anti-corruption campaigns should have a direct impact on public policy.

As it turns out, though, these implications are not borne out by real events on the ground—and this is true especially in countries like the United States.

In a paper entitled “Testing Theories of American Politics,” researchers Martin Gilens of Princeton University and Benjamin Page of Northwestern University present the results of a multivariate analysis, conducted by a large team of researchers, to compare the predictions of Majoritarian Pluralism and other leading theories in the study of American politics. Their research, which included measures of key variables for 1779 policy issues, is the most exhaustive study of its kind that has yet been undertaken.

“The central point that emerges from our research,” Gilens and Page write, “is that economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. government policy, while mass-based interest groups and average citizens have little or no independent influence.” The study refutes Majoritarian Pluralism, as well as the familiar Majoritarian Electoral Democracy view (according to which political power lies with the electorate), and it confirms the implications of two alternative views of American politics, which academics call Biased Pluralism and Economic Elite Domination. The later views are represented, notably, by Marxist political theory.

So let us be clear: the most exhaustive comparative empirical study yet conducted on theories of American democracy by “mainstream political scientists” shows conclusively that: (i) the view of liberal democracy that the American University and Armenia’s one-man-shop political parties have prescribed are inaccurate; and (ii) the Economic Elite Domination view and the Biased Pluralism view, represented most notably in Marxist political theory, far more accurately describe American democracy.

In America, just as in Armenia, the big capitalists as a group hold a near-monopoly on political power. In the USA, no less than in the Republic of Armenia, the rich rule. But then of course “we all know this”: it is lived experience of tens of millions of people daily. In highly stratified countries, wealth just is economic power; economic power is power over others; economic inequality is political inequality.

Yerevan’s pro-Western opposition might deny this truth, but it is not a recent revelation. In the book of Proverbs 22:7 we read: “The rich ruleth over the poor and the borrower is servant to the lender.”This insight is part of a “wisdom tradition” that goes back more than two and one-half millennia.

It would seem, then, that Armenia’s pro-Western opposition has swallowed political assumptions that fly in the face of everyday experience, ignore ancient wisdom, and defy the best contemporary empirical research by the best of America’s “mainstream political scientists” themselves.

In a previous discussion (“Armenians Need to Lose Their Faith in the Free Market,” Hetq.am, Feb. 7, 2015), we learned that recent empirical research, as exhaustive and careful as it gets, confirms that, in the West no less than in Armenia: (a) there are huge gaps between the rich and vast majority of the “citizens,” and (b) capitalism left to its own “free market” devices tends to increase the gap between the richest few and the rest.

To these insights, we may now add another: (c) in capitalist democracies, the richest rule. Conclusion: in liberal democracies of the West no less than in Armenia, “the free-market system” increasingly concentrates wealth, and thus political power, in the hands of a tiny minority of the population.

Yerevan’s overawed admirers of everything American, then, are looking in the wrong place if they really want an alternative to Armenia’s plutocracy. If successful, they would—once again--only replace one set of plutocrats with another.

One might think that this consideration, true and important as it is, would make a difference to political discourse in the Republic of Armenia. After twenty-five years of political manipulation, deeper and deeper poverty, and demographic disaster, one might expect that a generalized skepticism would prevail in Armenian today when it comes to the constantly repeated flimflam connecting capitalism to freedom.

The good news is that some of our young compatriots are learning lessons that the counter-revolutionaries of the 1990s denied, and that their parents were too exhausted to acknowledge.

Striking workers at the Nayarit plant make the connection between capitalism and plutocracy, as do protesters against privatized-bus fare hikes and electricity-rate hikes. So do those who oppose deforestation, strip mining, the privatization of public land, raging corruption, and the beating of dissidents.

These young compatriots do not take their petitions to foreign embassies, and they do not cast votes for the candidates of the one-man shops that pass for political parties these days. Through their actions they have shown that the best counterforce against the ongoing abuses by Armenia’s plutocrats is resistance from the bottom—from the streets, social media, offices, factories, and public squares.

The next step for these young people is to come together, to share lessons learned, to pool their resources, to organize not just against today’s plutocrats, but also against the ones who would replace them.

The challenge facing our young compatriots is to build a common vision and a common organization to fight against plutocracy altogether--and to fight for workers’ power.

(Markar Melkonian is a nonfiction writer and a philosophy instructor. His books include Richard Rorty’s Politics: Liberalism at the End of the American Century (Humanities Press, 1999), Marxism: A Post-Cold War Primer (Westview Press, 1996), and My Brother’s Road (I.B. Tauris, 2005, 2007), a memoir/biography about Monte Melkonian, co-written with Seta Melkonian)

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (4)

Write a comment