“This Institution Never Serves The Purpose It Supposedly Has”

Seta Kabranian-Melkonian

Leaning my head on his shoulder I listen to the translation of the Japanese sentences, mixed with Latin letters and Armenian notes. He is holding his burgundy prison diary.

“When we grow old and retire I want to write a book about prison. These notes will be needed then,” Monte says.

I smile. I imagine us grown old and grey together. Our kids, already grown and out of the nest and we, just like this, alone with each other again, talk about important issues. Maybe in the house he dreamt of building with his friends on the shores of Lake Kayladou in historic Armenia.

“You know, every judge should go to prison for at least a few months before becoming a judge. That way maybe they’ll understand where they’re sending people and how they play with people’s destinies,” Monte continues.

Of course I agree with him. We often discuss that whatever imprisonment will achieve would do so within the first few months or years. A twenty-year-old young person who commits a crime is not the same after five or ten years, let alone later than that. Unless the prisoner is a serious danger to society, it is absurd to keep them long let alone for life. And death penalty is plain unacceptable.

While we travelled in Europe for two years, every morning, immediately after breakfast, we took our books, pads and pens and rushed out. We went to a park or the beach and spent our day there. I’d noticed Monte didn’t want to stay in closed areas. “I spent so much time in prison that I want to be outside all the time now,” he repeated. Thus, we spent our time wandering, swimming, reading,writing and talking. And on rainy or snowy days we visited warm museums and galleries.

Monte stayed three and one half long years in prison. When I think of Mher Yenokian, Soghomon Kocharian, and other innocent prisoners in Armenia and elsewhere, I lose track of years because it’s a lifetime. Concentrating on Armenia, I wonder what Monte would have thought about all this. I wonder what he would have suggested that we do. My inquiry is partly unfounded because I know what Monte thinks about prison. On 19.1.86 he wrote in a letter: “It’s amazing how many intelligent people are in this place. Every body helps each other here. All of them gave me quite a bit of advice and things to read. There are too many things to learn from them. Here everyone is experienced and it is like a strange school. I will take advantage of my time as much as I can. Also, this whole condition interests me a lot. I want to explore the reasons why people are here. I want to understand what are the affects of this condition on people. It’s already clear to me that this institution never ever serves the purpose that it supposedly has. I want to examine this and then form an opinion about how it should be to serve its purpose. There are many people who never think about these issues, but when you are in this difficult situation you soonrealize how important it is to find the right solutions.”

Yes, there are too many people who do not think about these issues. Often concentrating on subjective conditions, instead of “finding the right solutions” they do the opposite. Months ago we witnessed such a case in Armenia thanks to the attitude certain people showed toward actor Vardan Petrossian. Let me mention first that I don’t know Vardan Petrossian in person. During my university years I’ve seen him on stage and been fond of his art. But, following the news of the fatal accident he was involved in, I can say that if there’s one person in this world, who wished most that the accident hadn’t taken place is Vardan Petrossian himself, I’m sure.

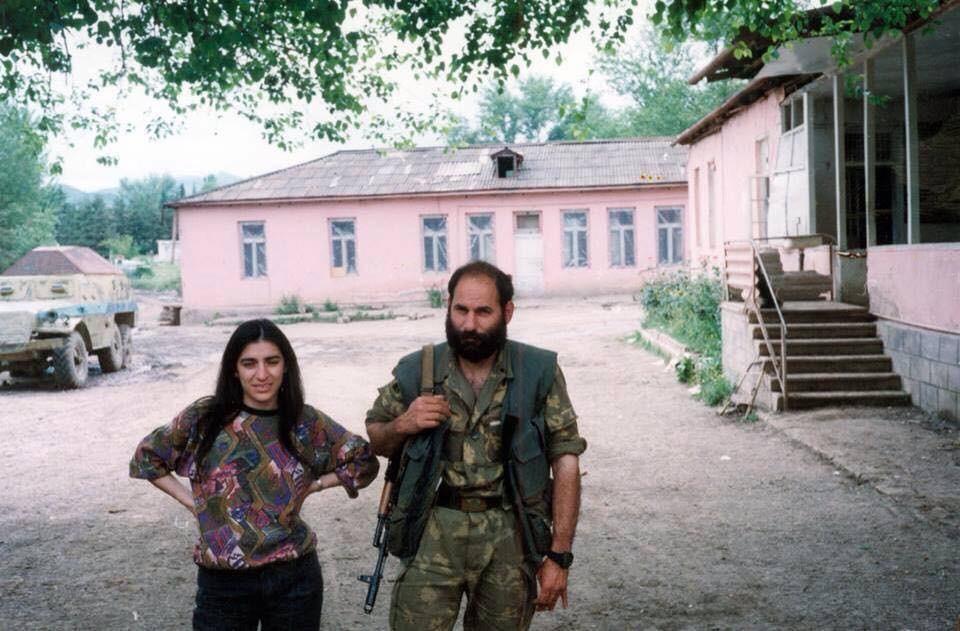

Immediately after Monte’s funeral our family left for Martuni where he was killed. His soldiers had informed me, that after the battle they had captured a hostage. Monte’s brother Markar and I wanted to make sure that we talked to the hostage. At the prison, a young man hardly old enough to shave was brought to us. When he saw us he made nervous moves and covered his face with his arm. He said something fast, almost like begging. He looked very scared. Surely he had heard about the infamous “sacrifices” that were common at the time when often, enemy soldiers were killed at gravesites. We assured him that he had no reason to be scared and we had come just to ask a few questions. When we got ready to leave Markar and I completed each other’s sentences asking the guards to treat the hostage well and if possible allow him to bathe. We also told them if they really wanted to respect Monte’s memory, they should exchange him at the first opportunity.

After ten months of absence when I visited Martuni again, I checked if the hostage was exchanged. A few of Monte’s comrades, who were not aware of our request, wondered how that hostage was exchanged so fast, when other hostages hadn’t for many months. The young man was an Azeri, a soldier of an enemy army. But after all he, too, was a victim of war, just like Monte was.

Infinitely optimistic Monte wrote to me from prison on 9.2.86 “I try to spend as much time as I can conversing with fellow inmates. The inmates in this section of the building are special and there are very interesting lessons to learn from them. It is a great opportunity to expand my knowledge. In this condition the camaraderie is very warm. Having the same difficulties everyone feels close to each other and helping each other is a basic rule. This place absolutely doesn’t serve the “purposes” that supposedly it has. Just the contrary, people get out of here stronger and more preparedin other things. It is a system that guarantees its own continuity.”

The building Monte was writing about referred to the section where political prisoners were kept. In the unofficial hierarchy of prisoners, political prisoners were the highest and most respected class. The lowest class wasthe rapists, pedophiles and batterers. Monte told me the prisoners that belonged to the latter group were disrespected and often “punished” by other prisoners. No one wanted to do anything with people, who exploited their physical strength and harmed women and children.

At the New Year’s Eve of 1991, Monte and I visited the homes of the members of his brigade. During one of these visits Monte and I watched in horror how the family members were treating the lady of the house. The husband and the in-laws treated her like a real slave. My efforts to help her met resistance. I was the commander’s wife, a guest and had to behave like one. It was unbearable to witness this discrimination. As soon as we walked out I told Monte I would never visit that house again. “I agree,” Monte said, “I, too, don’t want to come here again. I feel really sorry for that woman.”

Armenia is full of free people, who belong to the lowest class of prisoners that Monte described. And for a small country like Armenia the number of innocent prisoners who are the victims of theatrical trials is too big.

One day, Monte’s mother, touched by the treatment her son was getting, said to me “It’s unbelievable how these people love and praise Monte.” During all these years my answer has remained the same. “Monte earned this affection drop by drop, with just how he was.” I want to believe, that history evaluates people fairly. The unjust decisions made for the Mher Yenokians, Soghomon Kocharians and other innocent people will be on the conscience of the ruling and decision making officials.

A leader, who truly serves his people, sets the first example by correcting the mistakes made by others. Believe me, it’s easier to get into history by good deeds and justice. Any attempt of defamation, even by former comrades, will shatter in the face of a legacy that is truly built on Integrity, justice and good deeds.

Take Monte’s example.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (2)

Write a comment