“Home 45” - Yerevan’s Home of Political Activism and Street Art Forced to Close

By Florence Low

Among the rubble of neglected buildings in the artistic heart of old Yerevan, in a basement with an inconspicuous sign reading ‘45’ outside, lived Home 45, a space open to all, which never closed its doors to anyone - that is, until last Friday night.

In a city where there is little space for those who think differently to the dominant mainstream discourse, it was a refuge for those who needed a platform to debate, to discuss, to understand, to fight.

It was a home for activists, for artists, for anyone who wanted to change or challenge the status quo, using whatever skills, talents or resources available to them. Home 45 was their platform and their community.

It is through the nature of Home 45 as a free platform for discussion and debate that it became famous for political activism and protests, eventually attracting the notice of the authorities and thus bringing about the closing of Home 45.

Carine, an artist and regular at Home 45, notes that “[the authorities] feel danger. They think this space attracts protest people against the regime, against the [political] situation, and they can have a lot of input into destroying it”. With the investigations of the police came the eviction of the activists and end of Home 45, and on Friday they celebrated their so-called “Last Supper”, where they reflected on their time at Koghbatsi 45, and the future of the Home 45 community.

“There was a demand for it,” simply states Artak, a street artist, activist and one of the founders of Home 45, when asked how the idea for Home 45 came about. He describes how, two years ago, he and his friend Lusine, along with the activist group Counter Attack, suffering from the limitations placed upon them by any other public or private space, came up with the concept of Home 45: a space where everyone would contribute to the upkeep, and everyone was free to create and perform their art and their ideas how they wished. A place which would help people and encourage civic action, which would educate, challenge and rouse the rest of the community. They understood that it was not enough to carry out all the political action themselves; they needed a space which would inspire people to become involved in their actions too.

They found a space on Koghbatsi Street, an old, rotten underground cellar without running water, and they dedicated their own time and money into renovating the space. And as word of mouth started to spread, as friends brought their friends along, the space turned into a vibrant community. Carine, who co-founded aeon, an anti-café in the same neighbourhood as Home 45, comments, “we witnessed the process, how it became a commune, how it began to breathe, how people began to be involved”.

One of its key principles is that it was not based around a capitalist money-making concept, but around the idea that you “pay what you can”. It was a place not just to take, but to contribute your ideas, your discussion, your art. Anyone could come to Home 45 and hold a discussion, a movie screening, an exhibition. As an anonymous commentator noted, at Home 45 you were “always a participant, never just an observer”.

Narek, a photojournalist who become involved with Home 45 when he was photographing street artists, describes it as a place where “people could do many things which they couldn’t in other places without money. There were people with different ways of thinking gathering here. Here, young people had a chance to discuss many things. Home 45 helped the youth of Yerevan to create new things”.

Both Artak and Lusine describe Armenians as political and activists by nature, and Home 45 offered a rare place to cultivate and grow a community which was stronger together. It flourished during the Electric Yerevan protests in June 2015 as a place which offered refuge to the protesters. Carine recalls how, as a hidden place, people could go there to take a break from the protests, to smoke a cigarette, drink some coffee then go back to the street, and draw their posters and signs. Not only has it been a safe space during political protests, but it is also viewed by some in the LGBT community as a safe space in what is otherwise a homophobic culture, argues Murad. It is apparent that many activists are proud of the Home’s pro-LGBT approach when both Artak and Murad make sure that the rainbow LGBT flag is in the background when I ask to photograph them.

Home 45 was Yerevan’s home to art and activism, “one of the few public spaces where anybody could come learn about activism and street art”, according to an anonymous regular at Home 45. The concept of the space as a free platform was of particular importance to the artistic community, since it was envisioned by its founders as a free platform for artists to do whatever they want, to make their dreams come true, whilst everywhere else there were conditions and limitations on their work. Carine held an exhibition of her art here in February, and describes how Home 45 had transformed her attitude to her art and introduced her to a philosophy that you don’t need a lot of money to show art, that you can self-organise and take it less seriously, and she cites a huge boost in her confidence which she puts down to her exhibition.

Some of Home 45’s most exciting innovations came from when these worlds of art and activism collided. Its activists have been the artists of numerous political street art which were removed swiftly by the police. Among its innovations, Carine mentions in particular a wedding they held at Home 45 last year between Artak and another Home 45 activist. She explains it as a rebellion against the traditional Armenian wedding “because there is so much artificial stuff... [Armenian weddings] became something ridiculous...the money they spend just to make people feel envy, [they] said that if people love each other they don’t need money, they don’t need ritual, they don’t need to invite so many people they don’t even know”. It was based around the idea that they just wanted “love as it was, no matter how long it lasts”.

She also describes the importance of that space for her personally; when she was suffering a period of depression, she used Home 45 as a safe refuge, when there was nowhere else to do art; for her, a place of art therapy. Home 45 was therefore not just a place of impact for the community as a whole, but for individuals on a personal level too. Lusine, one of the founders, says “Home 45 is a home; there is nothing else to be added”, and it seems that the use of Home as a refuge, as a safe space, as a home, has been incredibly important for people. Many of the people I speak to at the closing party recall fondly a time when they needed a place to stay and Home provided that for them; Ani, for two nights on holidays from Lithuania; Murad lived here for a week; and Artak remembers a time when Home hosted 30 hippies from the Rainbow Gatherings. Moreover, everyone who tries to recall a favourite memory from Home 45 simply says that all memories are good; it is clear that Home is much more than a basement room with art on the walls, but a community. This is particularly key in a country like Armenia; Carine argues that Home’s lasting legacy was to introduce the idea of community to a people who are very attached to private property.

It was its participants’ protests about the imprisonment and ill treatment of political prisoner Vardges Gaspari which finally attracted the attention of the authorities. After the arrest of Gaspari in early 2016, Artak and the other activists from Home 45 went to the presidential residence, where they planked outside demanding his release, and there was a discussion held at Home 45 about the issue. Soon after this, many police officers started to come to Home 45 to make enquiries. They found the landlord and, discovering that there was no legal contract for renting the space, used the fact that it is illegal to rent a space without a contract to force the landlord to evict them from Koghbatsi 45. Although Gaspari was freed, the activists had to move out. And, as Arman argues, it is through these events that you can see the true impact of Home 45: “If Home hadn’t changed anything, it wouldn’t be closing. If the street art didn’t change anything, they wouldn’t erase it”.

But will its community survive the removal of its base? Both Carine and Narek note the decline that was taking place in Home 45 for many months before the police arrived to evict them, and they blame it on the Yerevan culture of getting used to new services, taking them for granted, not making their own contribution, both in the upkeep and in planning the events and activities. Carine notes that the spirit changed when different people started coming, who only complained about the political and social situation in Armenia, and were not willing to make action to fight against it and “making [Home 45] rot”, pointing out the numerous fundraisers that were necessary to help Home 45 pay bills towards the end. Artak argues that Home is not a space that is needed any more; if people needed it, they would contribute, or they would set up similar spaces based on the same concept, which has not happened so far.

When discussing the future of Home with its regular participants, it is overwhelmingly clear that it is not the space which is important; it is the idea. Likewise, when considering its impact, Artak argues that we should not pay attention to Home’s actions themselves but the ideas, and in fact this seems to be Home’s most important legacy, that it was a space with the power to change people’s opinions and mentalities concerning different issues, for example Murad references homophobic people whose opinions concerning LGBT people were changed upon going to Home 45. Likewise, the concept of Home 45 has now been shown to the public, and Artak welcomes anyone who wishes to copy the idea. They have created the audience, the community, and now they are free to take the ideas to any place. Carine, discussing the police’s tactic of ‘divide and conquer’ to get rid of the activists, argues that “they don’t understand that it’s not about the place, people can sit in the park, in the street, in Baghramyan”. Narek comments that “I don’t want to speak about Home in the past tense. It exists, and there was a time when it was created, and I think Home, as a concept, will exist as long as these people exist, and it doesn’t matter the place”. For Artak, their location from now will be the street, and they will never have a permanent home, because wherever they go, they will be asked to move. There is an overwhelming sense among Home 45 participants that the idea of Home will long outlive any location in which it finds itself; the idea is out there, and it is for people to do with it what they can.

Florence Low is from London, UK, and currently lives in Yerevan, Armenia. She works as an events coordinator at aeon anti-café, and is involved in women’s rights and LGBT activism in Armenia.

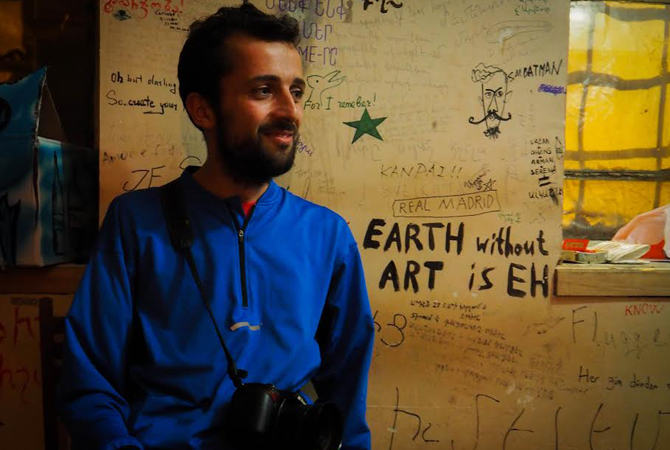

Top Photo: "Artak, activist, street artist and co-founder of Home 45, behind the bar."

All photos by Florence Low

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (2)

Write a comment