Armenia’s Lake Gosh: Building Eco-Tourism or a National Eyesore?

Gagik Aghbalyan

Armenia’s Lake Gosh today looks like a large pool of muck.

The Vendor company has brought in heavy construction equipment into the Dilijan National Park, widening the road to the lake and removing mud from the lake’s basin. The mud is being dumped around the lake’s perimeter.

The local rumor going around is that the lake has been purchased by a son-in-law of Armenian President Serzh Sargsyan in order to build a hotel nearby.

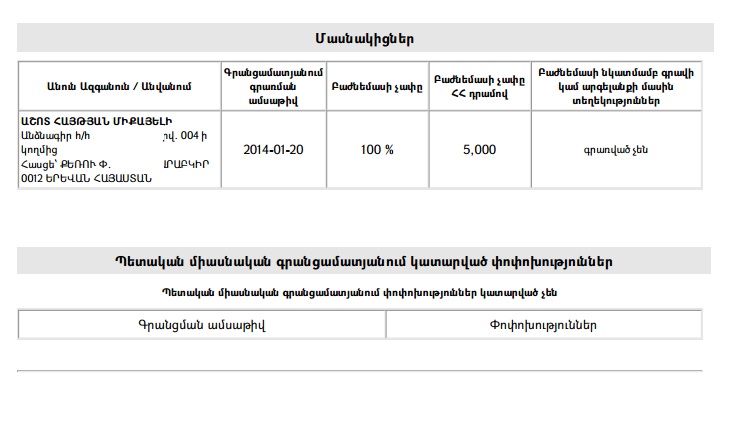

Vendor was formed in 2014 by Yerevan resident Ashot Haytyan.

On July 3, 2015, Haytyan and Dilijan National Park Director Sahak Mouradyan signed an agreement by which a parcel of land in the park’s Gosh branch was allocated to Vendor for commercial use.

3.18hectares was leased to Vendor, at an annual rate of 1.330 million AMD, and a construction permit issued with an expiration date of July 2075.

The contract stipulates that construction must not upset the lake’s ecosystem and that motorized boats would not be permitted without approval by the environmental ministry. The company would also have to restore a pedestrian walkway around the lake’s shoreline.

Vendor has brought in an excavator without notifying Dilijan Park management in advance.

Park Director Mouradyan told Hetq that he was on vacation for over one month, and would still be away from the office for a few days due to personal issues.

Deputy Park Director Vaghinak Vasilyan said that the company hadn’t notified them, but that construction work had been put on hold. “They told us that the work was legal, but we asked that they stop work for now until we understand what is going on,” Vasilyan told Hetq.

Vendor representative Edward Melkonyan, who told Hetq that he’s the brother of Ashot Haytyan, described the work as “cleansing the lake of waste water”.

“The level of mud in the lake has risen. There are spots where the water is only 20-25 centimeters deep. Plants are starting to grow there. It’s turning into a swamp. The excavator is deepening the lake’s basin so that the water doesn’t warm,” Melkonyan said.

Melkonyan said the company has won a bid announced by the environmental ministry, but that they don’t have the finances to make any substantial investments on the site.

When asked what the company is planning to build in the park, he answered, “We have no plans at the moment. We haven’t constructed anything yet. We just decided to halt the silting process and clean the lake. Our long-term plan is to build wooden cottages near the lake to spur eco-tourism.”

The contract stipulates that Vendor invest 300 million AMD (US$618,200) within five years. Cleaning the lake, roadwork, and building the cottages are included in the investment.

Vasilyan believes that the construction will not damage the environment.

“They will not damage the forest. They’re simply fixing the road to Lake Gosh,” he says.

While Vasilyan says the company doesn’t have a permit to dredge the lake, Melkonyan, his boss, says the opposite.

When asked if the company had a permit to dredge the lake, Vasilyan said, “I knew the muck shouldn’t have been removed. But I checked, and found out that the company merely removed dead trees that had fallen in.”

Vasilyan, however, hasn’t visited the site in the past few days, and hasn’t seen what’s going on with his one eyes. He relies on what others tell him.

So, what’s the fate of Lake Gosh?

Can the current construction actually spur eco-tourism?

The environmental ministry has given the go-ahead to a company that has, as Melkonyan confesses, no experience in eco-tourism.

The fate of the lake, like so many other cultural and historical landmarks in Armenia, is in the hands of non-professionals.

To make matters worse, Dilijan National Park management seems to have no clue about what’s taking place under its nose.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (1)

Write a comment