Soviet Socialism and the Difficulties of Repatriate Integration

Aghasi Tadevosyan

Cultural Anthropologist

The generation that lived in Armenia during the 1970s well remembers the repatriates, who were commonly called “akhpars”. These akhpars were the people who upset the general bland uniformity of a neighborhood. It was the way they dressed, their interests and way of life. Many will also remember that their number started to gradually diminish from the mid-1970s onward.

The neighborhood in which I live, was once inhabited by repatriates. During a conversation with a longtime resident, I found out that of the eleven families that had repatriated after 1946 and lived in his immediate vicinity, eight had left Soviet Armenia during the 1970s and 1980s, primarily to France and the United States.

According to many of the interviews conducted with repatriates, they started to have suspicions and concerns from the very first; when entering the Soviet Union. People realized that they had wound up in a place absolutely at odds with their imagined homeland.

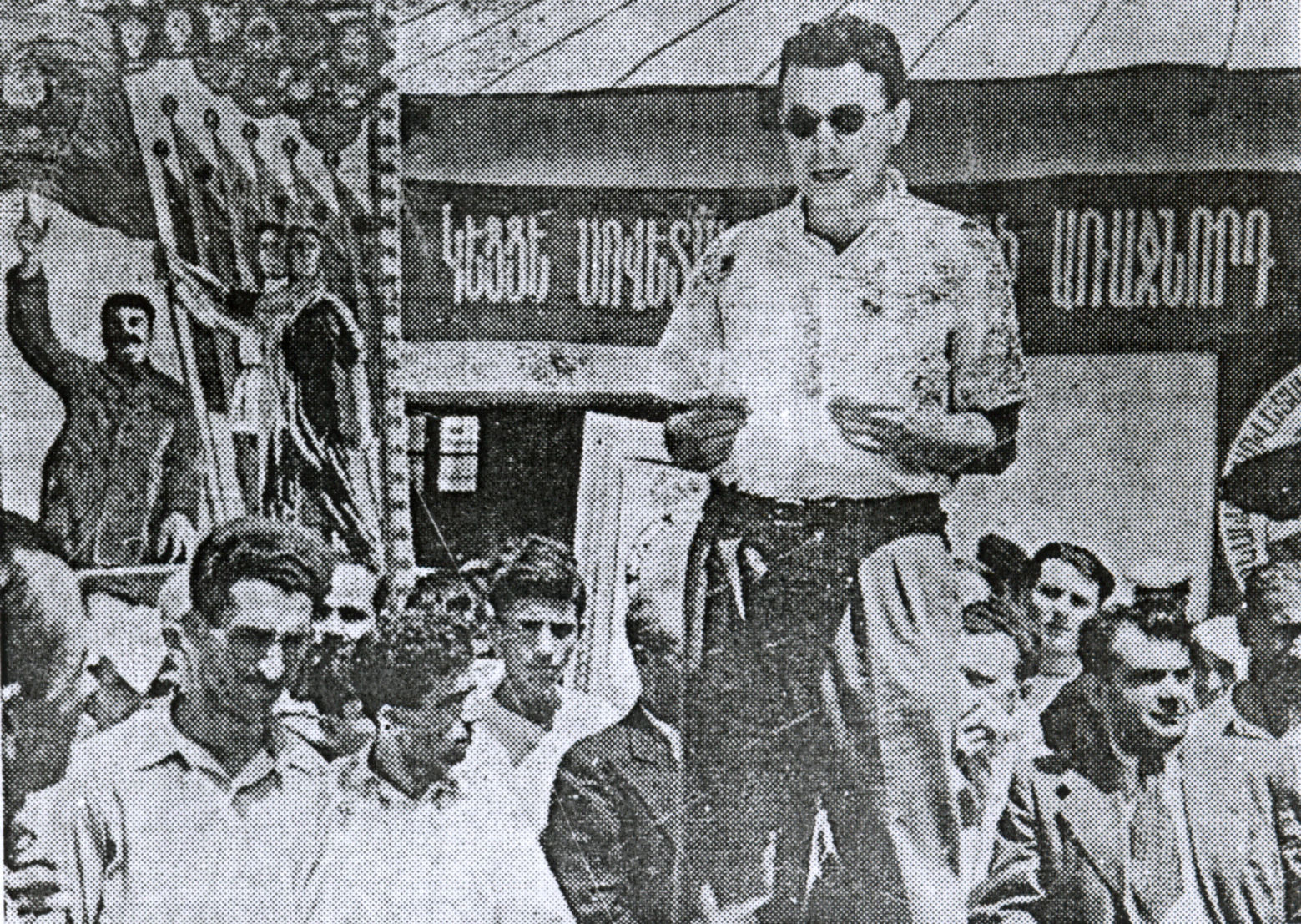

Better life promising campaign, Beirut, 1946

The principal problem was the dominant system in Armenia. We are not only referring to official, but also non-official, practices. All the repatriates were from capitalist countries and had no clue about Soviet socialism. The huge system of punishment, the arbitrary conduct of officials, incarceration, administrative roadblocks, was new to them. Their nonfamiliarity of the country they were moving to, their lack of information, can be considered the most glaring aspect of the repatriation movement and the prime factor of its failure.

Welcoming repatriates in Yerevan railway station, 1946

Months after setting foot in the homeland, many tried to escape. The shock of the first few days is probably the reason that many of the newcomers were never able to integrate into Soviet Armenian reality despite living in Armenia for decades.

They remained isolated, never leaving the confines of their four walls. They had no comfort zones other than being with their repatriate friends and relatives.

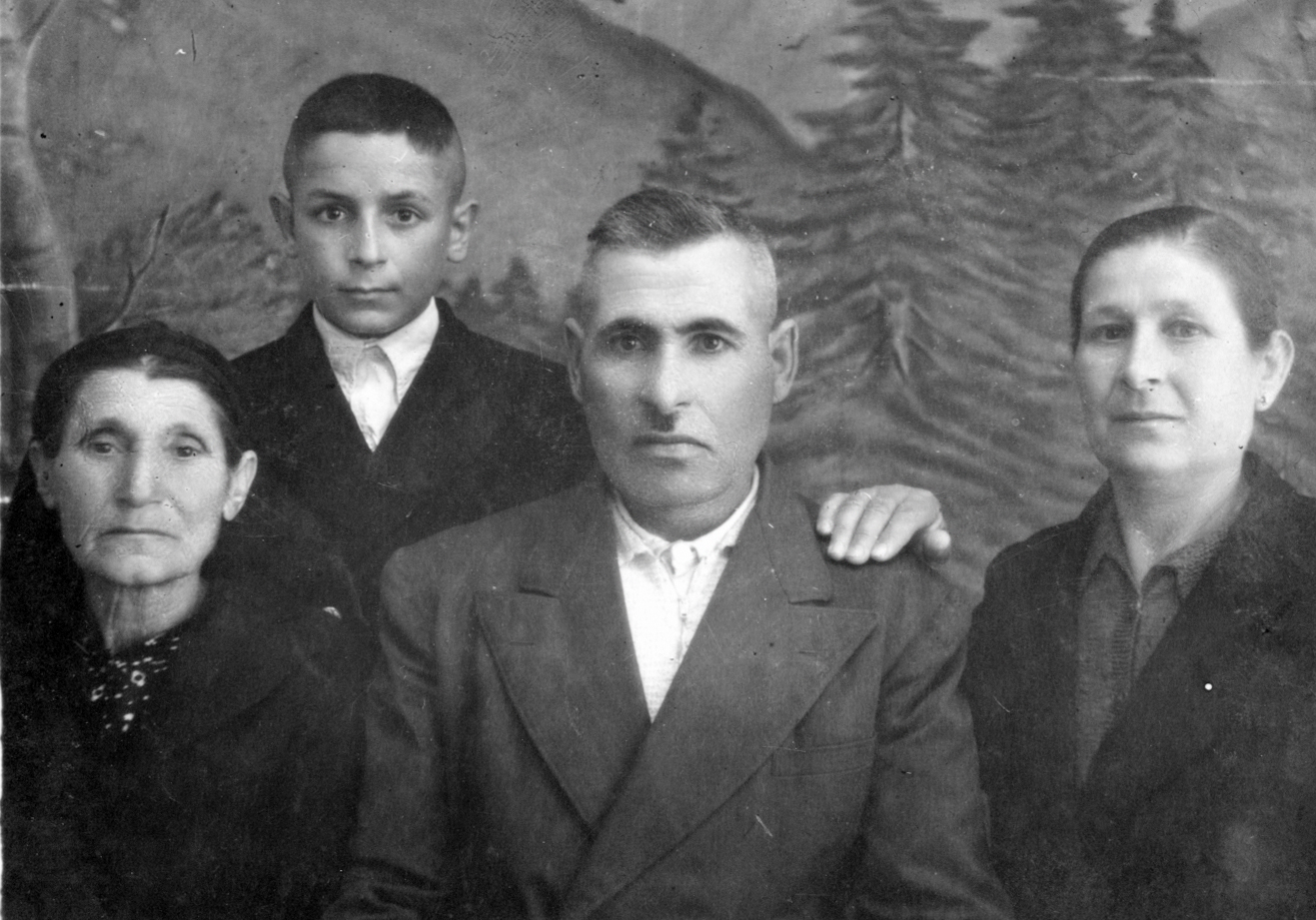

Family of repatriates, first photograph in Yerevan

They could never describe that (Soviet) reality as being real for them. Their real world remained outside the borders of the Soviet Union – in those countries where they came from or in those countries they were told about by relatives.

In this respect, the repatriates can be equated with the Indian actor in the film One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest who didn’t accept the reality of the psych ward and didn’t try to change it. Thus, he was able to retain his mental edge and, finally, to escape. Jack Nicholson, the film’s other protagonist, lost his grip on reality. Accepting the psych ward’s inner world as reality, he began to fight to change it and, in the end, became one of the institution’s despondent residents.

Sewing shop in Yerevan, 1950s

The ranks of the repatriates included many artisans. There were also mid-level and upper level entrepreneurs. They believed that they would move to the homeland and continue the work there. They believed this because the agents/propagandists sent from the Soviet Union to the Armenian communities in the Middle East mentioned nothing about the difficulties awaiting them in Soviet Armenia.

Social problems and perception complications

A review of the data culled from interviews with repatriates shows that from the start their main problem was getting a grasp, an understanding, of their new surroundings, and of adjusting to the shock of it all.

PEPO ISHLEMEJIAN

Repatriated from France in 1947 / Lives in Paris

My father was a director of a factory here. It was a factory that sewed bags. He worked on the up and up. Once some guys came to his office and said, “Don’t work like this. Cut one meter and give us the other. We’ll give you your share.” He said he wouldn’t and left that job.

They didn’t understand where they had landed and what they were supposed to do in their new land. From day one, the repatriates faced the problem of housing and food. The repatriation organizers and propagandists had told them they would receive apartments and work upon arriving in Armenia. On the contrary, upon arrival they were faced with the most basic of challenges – daily survival.

In addition, the nature of the system gradually became clear. It was crude, authoritarian, and totally indifferent towards the dignity and fate of the individual. The system was full of violence, fear and barriers.

The difficulties of engaging in business

The barriers erected by the Soviet state regarding engaging in business, creating something on an individual level, of earning money, were the biggest obstacles when it came to the integration of the repatriates.

As noted, many of the repatriates were artisans and craftspeople – tailors, shoemakers, jewelers, furniture-makers. At first, they expected government assistance in starting their businesses in the homeland, not only allowing them to support their families but also spurring economic development in the country.

LOUSIK GHOURJIAN

Repatriated from Syria, 1947 / Lives in Yerevan

The repatriates brought great riches to Armenia. Some brought shoe factories, some brought printing presses. For example, the Bulgarian-Armenian Kaprielian brothers founded the Hairenik shoe atelier. They brought Dobel machines to Armenia. I worked there from 1953-1954. All of them were then deported and became common laborers.

There were also mid-size and large entrepreneurs amongst the repatriates who, never being informed that private business was not permitted in Soviet Armenia, spent huge amounts and overcame great obstacles to have their production plants, expensive equipment and all, moved to Armenia.

Arriving in the port of Batumi, they realized that they were not only to be deprived of the right to manage their production resources, but that they could also be charged with violating Soviet law by fostering capitalist economic norms and either thrown in jail or exiled.

The repatriates didn’t understand the logic at play. Instead of encouraging and assisting them, the state was filing charges against them as enemies of the Soviet system and threatening them with imprisonment.

The unwritten laws of the Soviet regime and the inexperience of dealing with the nomenklatura

The “man from the finbazhin” (financial division) was a mystical Soviet official who monitored the activities of those engaged in home-based and other small businesses. We encounter references to him in almost all interviews with repatriates.

Those working out of their homes, for instance craftspeople, would place a family member outside the door to stand guard lest the finbazhin man showed up. This way, the alert would be sounded and all traces of the work going on inside would be cleared away. Once the inspection was passed, for the umpteenth time, work would recommence. Even if caught red-handed, the repatriates had already learnt how to deal with Soviet mid-level bureaucrats. They would grease their palms and the inspections would temporarily stop. The repatriates thus adjusted to their new situation without understanding how operating a business could be deemed a chargeable offense.

ANI AMSEYAN

Repatriated from Egypt, 1947 / Lives in Glendale, California

She was good at handicrafts and started to take all the fabric in the house, cut it up, and then refashion and sew it. Later, she started to sew blouses and other things. The work was so good that she started to get orders. Of course, she worked in secret and in fear of the tax authorities. We lived in that constant fear.

While it can’t be said that native residents were in better shape, but being born and raised in the Soviet system they accepted all this as the norm. Repatriates, however, protested, and while they didn’t express themselves publicly, that resentment remained with them.

It can be said that the impossibility of conducting business was the principal factor preventing repatriates from integrating. Today, the influx of Syrian-Armenians to Armenia and the relative ease with which they integrate into a new environment, is mainly because they can engage in private business.

Many local Armenians prefer to patronize Syrian-Armenian restaurants, car repair shops, stores and tradespeople, viewing them as honest and well-run. The private sector is making it possible for locals and newcomers (Syrian-Armenians) to get to know one another.

The absence of such a possibility in the Soviet Union greatly inhibited the integration of the repatriates. In many cases, it made staying in Soviet Armenia impossible.

This article is prepared within the framework of “Two Lives: The Cold War and the Emigration of Armenians” project financed by National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (1)

Write a comment