Records for Morua

"Whatever I read about him, it is not about him."

Gajane Khachaturyan, a friend and painter who still lives in Tbilisi , says what many others say about the artist/director Sergey Parajanov. Svetlana Shcherbatjuk, who divorced him in 1967 but remained his friend, says journalists writing about Sergey Parajanov more often make up stories. "Afterwards they like it and they believe in what they fabricated, and they write those stories, as if it was reality. I got burned with it so many times!" says Shcherbatjuk as she asks a "Brosse Street Journal" reporter not to do this. "I set hopes upon your conscience!"

Albert Yavuryan, an old Armenian friend and cameraman who lives in Yerevan , says Parajanov could make a legend out of every story. "One doesn't need to make them up," he said. "Just record the ones he really did. And that's it!"

Khachatryan says: "Each person who knew him for 10 minutes writes about him."

"He is a mystery, and it is impossible for anyone to reveal him! Even he wasn't aware of his own mystery!" Yavuryan says.

"I guess Andre Morua (the great French writer who wrote fiction based on real-life famous people) should be reborn to write about him," Khachatryan says.

So here are some facts recorded for Morua if he ever returns.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Saturday, November 6, on a square in the center of Tbilisi , two kids tear off the curtain from a monument and everyone sees Sergey Parajanov, appearing in his native town again. The opening ceremony for the monument is dedicated to one of the world's 100 greatest filmmakers' 80 th anniversary.

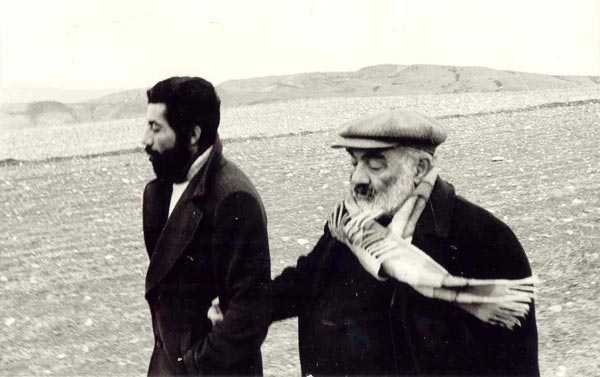

The sculptor Vazha Mikaberidze was inspired by Parajanov's photo which was taken by Yuri Mechitov, a friend and artist who still lives in Tbilisi . Parajanov is illustrated jumping with wide-open arms.

Said the Tbilisi-born Mikaberidze, who now lives in Italy : "I think that this photo perfectly illustrates a person who is filled with inspiration and joy. I tried to show this joy in my sculpture."

Guests at the ceremony agreed: 14 years after his death in 1990, Parajanov finally came back to his lovely Tbilisi , this time flying.

A Filmmaker Once and For All

Parajanov's biography indicates that his life changed in 1984 thanks to several Georgian intellectuals. After that he created two movies, the Georgian "Legend of Suram Fortress" and the Azeri tale "Ashik Kerib."

He started his last and unfinished "The Confession" in 1990. He had done no films since 1986. What filled that gap of almost four years?

Yavuryan says Parajanov found an alternative to his cinematography in his collages, dolls and paintings. "And when friends came to visit him, it could replace cinematography for him, because it was theatre, it was for him excitement and inspiration. He was always in such state. Interminable. He didn't rest like the rest of us. He just took a breath and kept working. After 2 am , when Kote Meskhi Street finally became quiet, he slept, but when the street woke up again at 6 am , so did he. Parajanov was unique, because through all this activity he kept his unique individuality," Yavuryan said.

But was the filmmaker thinking about a new movie? After all, he finally was allowed to create films, and that process was important for him.

Yavuryan says that from prison Parajanov wrote to him, advising him to become a filmmaker: "Step over your fear! It doesn't matter if you gain white hair." In another letter he wrote to his wife:" I told Roma (Balayan, an Armenian film director based in Moscow ) not to hurry becoming a filmmaker; the most important thing is becoming a filmmaker once and for all."

Kora Tsereteli, a Georgian film critic and cinema theorist who lives in Moscow , writes in the introduction to Parajanov's script "Martyrdom of Shushanik" (printed in St. Petersburg in 2004), that after the Soviet Union collapse in the late 1980s, national movements developed in the Caucasus . Zviad Gamsakhurdia, a nationalist political activist, writer, literary scholar and translator, came to power in Georgia . (He eventually was elected president in 1991, one year after Parajnov's death). Parajanov and his art became a perfect target for the nationalists in Georgia . In media and from rostrums, Parajanov was blamed for distorting Georgian culture and history in his movies "Legend of Suram Fortress" and "Arabesques on Subject Pirosmani." (Pirosmani is perhaps Georgia 's most famous painter.)

There was gossip that Parajanov was going to shoot one more legend based on Jakob Tsurtaveli's 5 th -century story about the Armenian-born Princess Shushanik, who was tortured and killed by her Georgian husband because she was devoted to Christianity. Tsereteli writes that his friend, Georgian Film studio director Rezo Chkheidze, put the script in his safe and didn't allow him to shoot this film in order to prevent Parajanov from nationalistic aggression.

Lost Treasure

Chkheidze had been Parajanov's friend since their student years. He says that he never put the script for "Martyrdom of Shushanik " in his safe. He says he has never seen that script, if it exists, but adds that Parajanov could have started shooting the movie without a script. "I wanted that film to be made. Sophiko (Chiaureli, a famous Georgian actress who Parajanov also called his Muse) also wanted it very much," Chkheidze says.

The only reason Parajanov didn't shoot that film, according to Chkheidze, was the lack of time: "If he had lived longer, he would have made it."

Avtandil Varsimashvili, the art director at the Tbilisi Theatre of Russian Drama, says: "I don't think it (the possibility of national aggression) was serious. Guram Petriashvili, who wrote some articles against him, was a chauvinist. Some tried to act against Parajanov, but everybody believed that he was a genius, that he should make films, and that they must help him." Varsimashvili says he doesn't think anyone stopped Parajanov from shooting "Shushanik." "It wasn't his top dream. He even wasn't sure what to shoot," Varsimashvili says.

Yavuryan says that Parajanov was disappointed by the feedback to his movie "The Legend of Suram Fortress." Yavuryan describes him as a very perceptive person who lived in harmony. "He couldn't have any problem with Georgian history. There could be only a problem with the perception of what he created," Yavuryan says. He adds: "About (problems with) Gamsakhurdia, I don't accept this. I didn't hear from Parajanov about that."

Khachatryan says that at the end of his life, Parajanov became difficult. "The beginning of Gamsakhurdia's era, he could hardly stand. He kept saying that nothing would remain (of the multicultural nature of) Tbilisi , and that it would be very difficult to live there," Khachatryan said.

Yavuryan tells about an interview with Parajanov, which was sent to him from Kiev after Parajanov died. Journalists came to Tbilisi from Kiev . "They wanted Parajanov to be more positive toward Perestroika and Gorbachev. They wanted to cheer him up and inspire him, so that he would dash farther ahead into his artwork. They said to him: 'Do you see they let you go abroad, you are free to move, they don't check your belongings and luggage?' Parajanov answered: 'They don't check, yet they don't trust me.' Then he raised his finger and said: 'It becomes more terrifying to live. The Soviet Union , this medley; this mob of nations, shouldn't be governed by methods like this. There is a need for Stalin.'"

He says Parajanov didn't support or even understand Perestroika. "He was persecuted, tormented by the system which Stalin had created. It didn't let him leave and work. And suddenly it turned out that it was the only system under which such a federation of nations could survive," Yavuryan says.

Chiaureli says that he didn't distort Georgian culture in the movie "Suram's Fortress." She is the one most directly involved in this story: the script and the role of Shushanik were written especially for her.

"There were some articles in the media against Parajanov, but when he wanted to shoot 'The Martyrdom of Shushanik' I said to him openly: 'Don't call it Shushanik. Call it whatever, but not Shushanik.'"

Yuri Mechitov says that there is Armenophobia in Georgia , and from time-to-time it leaks out. Can that be the reason he did not shoot the film?

As Chiaureli points out: "It is a little bit of an oversensitive issue, because of hostility between Armenians and Georgians regarding 5 th century history and the legend of the Armenian-born Georgian princess. Georgians say it's Georgian legend, Armenians say it's Armenian.

"I just had a presentiment that it might happen. They would ask why an Armenian should do that film when there is such hostility. And that's what happened. There was a bad coincidence of the nationalist movement starting, along with government changes. Some were against making such a film, and some were for it. So the making of this film was stopped quietly."

Chiaureli says there is one thing she can't forgive herself for. "Frunzik Dovlatyan, a filmmaker and Director-General of Armenfilm studio in 1989, came to me and asked me to go to Armenia to shot "Shushanik" at Armenfilm studio. But I thought it would cause even worse problems. I would have to move from Georgia to Armenia ," Chiaureli said jokingly. "And I refused to go. I refused and now I regret doing that. Because the world has lost a very tremendous work of art. How it was written, and how it could have been handled in Parajanov's hands. It could have been his best movie. But fortune arranged it differently."

Nevertheless, she doesn't think it was crucial for Parajanov.

"The fact he wasn't allowed to shoot "Shushanik" of course affected him greatly," she said. "But Sergey was a cheerful, humorous, buoyant person, and he adored life. He knew what was he worth. He knew that soon or later he would do this. He believed in it. If you mean did it affect him fatally, move him nearer to his death, I don't think so."

Yavuryan says Parajanov was working with all his heart: "Each script he wrote was already staged in his head. But when he lost something, he didn't consider it as lost, because he was a generously gifted creative person. And so much remained!

"Maybe not staging 'Shushanik' was better than if it had been staged, because it is one more colorful story in his biography."

In 1990, Chiaureli says, "unfortunately civil war started in Georgia . Parajanov moved to Paris to the hospital and Armenians took all the stuff from here."

Khachatryan says Parajanov himself started to send his works to Armenia .

Shcherbatjuk confirms this: " It was he who started to sell his works to Armenia. He also bequeathed them to the museum in Yerevan. And he wasn't wrong. He was a prophetic person. If he didn't do that, everything would have been lost. The time was muddy, uneasy."

Suren Parajanov says his father wanted to move to Yerevan not only his works, but also all his furniture. He wanted to move to Yerevan , but the house wasn't ready yet. "And when after his death they (Armenians) started to transport all this stuff, I was a little bit insulted, because they had no right to do it without my permission. But now I think that it was right."

He says that the works in the museum are in good condition, the exhibition is always renovated, and the attendance is high. (The ticket price is affordable -- approximately $3).

Even presidents of countries visit it. "When the Yerevan museum started, in Tbilisi it wasn't possible to do the same," Suren Parajanov says.

Chiaureli says that the museum in Yerevan is wonderful, and that the director, Zaven Sargsyan, takes care of it. "On one hand I am glad there is such a museum in Yerevan , on the other hand it is so insulting that the museum is not in Tbilisi . In fact the museum belongs in Tbilisi ," she says.

Sargsyan says that he started buying Parajanov's works in 1986, when he was the head of another museum, The Armenian Museum of National Art. During the Soviet period the museums had funds for purchasing new works from all around the country. "And when I went to Parajanov and said to him that I would like to buy his works, he was very surprised: no one was buying his works at that time."

One of Sargsyan's first purchases was a set of ceramic works for 40 Soviet roubles. "We bought all his works that he created from that time until his death. During the 13 years of our museum's existence we have doubled our exhibition," Sargsyan says.

Chkonia says that in Georgia they feel guilty about losing Parajanov's house and museum. She says she has initiated the idea to make a two-room Parajanov museum in Tbilisi . "The fund has already bought the two rooms, because there are lots of people here who have Parajanov's works. They don't need to make a gift or sell the works to the fund, but only to expose them."

She says she has announced this plan and received no feedback.

Chkheidze says: "I plead guilty both myself and for my colleagues. We are guilty of not having Parajanov's museum in Tbilisi. Why we didn't fight for it? That's why I was happy to see that monument which was opened recently. But we have to redeem our fault in commemoration of our Greatest Master."

Suren Parajanov says if there is a need for a museum in Georgia , they will find funds. "So far the monument has been built. There is no need to hurry up: everything will come with time. And time will show what Parajanov is worth. It is in the process. His movies don't wear out, not physically, not morally. He is becoming more and more popular in the world. And without advertising."

He Needed Only Material

Khachatryan says that when she asked him "when he became Parajanov," he answered: "after four shocks in my life." Parajanov told her only about two of them.

In Moscow he married a girl who worked in the VGIK (Cinema Institute) cafeteria. She was a Kyrgyz. Before getting married in her native town, Nigjar had been engaged to a Kyrgyz man, who according to national traditions paid for her. Parajanov gave her money to pay him off. On her way back to Moscow her body was found torn to shreds. Parajanov collected the parts of her body and read the message on it, that every girl who will violate national traditions will meet the same destiny.

Shcherbatjuk tells this story a little bit differently, but also says that it was Parajanov who told her the story. "Nigjar was a very beautiful Tatar woman. She and Parajanov were secretly married. But every secret becomes uncovered," Shcherbatjuk says, adding that the fiance killed Nigjar and put her body on the railway to imitate a suicide. It was Parajanov who had to go to the morgue and identify her body. "After that he had to interrupt his study for a year in order to be cured for shock in Tbilisi. He was recovering slowly and painfully in dark rooms," she says.

Khachatryan says the second shock Parajanov told her about was a disease when he was 40. He would not tell her what disease it was. She says he also didn't tell her about the other two shocks.

Shcherbatjuk says she is not going to guess. " If he didn't tell the other two, I also will not." Nevertheless, she says their divorce was a shock for him, and maybe more than for her. "But I don't know if he considered it as one of these crucial shocks," Shcherbatjuk says.

Shcherbatjuk knew for sure one more shock in his life. She says that before his health got worse in 1989, he had started making what was perhaps his dream film " The Confession" in the yard of his native house. During shooting, a neighbor child was too interested in what was going on. He came too close to a candle on the movie set, and his shirt was burned. Even though he wasn't injured significantly, Parajanov paid the boy's mother to take care of her child." (Parajanov) was shocked greatly. He said that it was a bad sign, a very bad, evil omen," Shcherbatjuk said.

The film remained unfinished. He became very sick and had to stop work after having shot only three scenes.

To the question of where are the roots of Parajanov's genius, Chiaureli answers: "It's from God. There had to be a reason. Some tried to pretend being Parajanov, even talented people. But no one managed to do something even close to what he had done. All them were imitators. He was gifted from God. He created beauty everywhere and from everything."

Yavuryan says: "Everything he touched turned into something sacred. The same even with junk, trash. And you could see how junk started to shine like a rainbow."

Chkonia says: "He didn't need an inspiration; he always had one. What he needed was only material."

I Pray For You

Yavuryan says, "The theme of death he touched in his novel "Rotterdam Seagull." In Rotterdam the seagulls smelled gouda chess, which he had hung out a window to keep fresh. They wanted to eat it and tried to tear apart the sack. They didn't manage, because the bag was a Soviet production and very strong. Parajanov writes: 'They flew away, being unable to tear to pieces Soviet sack.' Parajanov finishes the story: 'Someday, when you pass by that hotel and see seagulls dash against the window, that means either I pray for you or I have already passed away.'"

Special thanks to Edik Baghdasaryan, John Smock, and Yana Fremer for their contribution to this work. Parajanov's photo is provided be Gajane Khachatryan.

The main picture: Yuri Mechitov

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment