Transitional Justice in Armenia: International Expert Dr. Nadia Bernaz Discusses the Process and Challenges

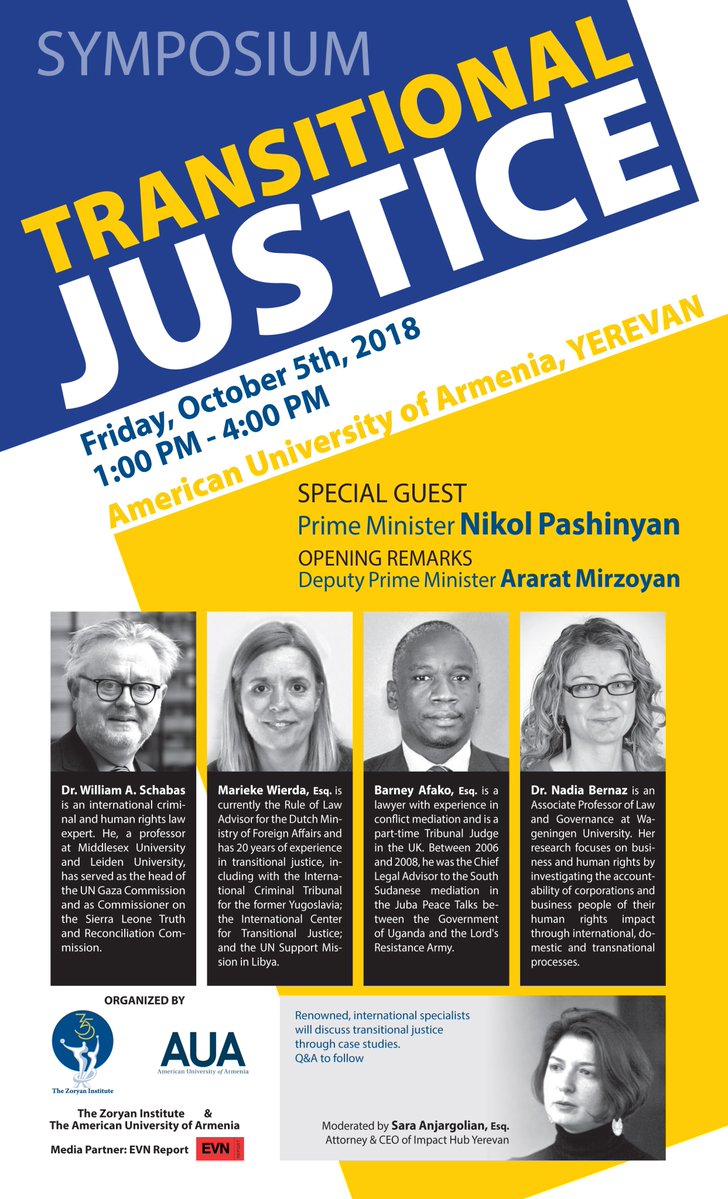

On October 5, the American University of Armenia (Yerevan) hosted the International Symposium on Transitional Justice organized by The Zoryan Institute. Samson Martirosyan interviewed one of the speakers - Dr. Nadia Bernaz, an Associate Professor of Law at Wageningen University, for Hetq. Dr.Bernaz focuses on the interplay between the business sector and human rights, investigating the impact of corporations on human rights, corruption and white-collar crimes.

Q - Dr. Bernaz, thanks for coming to Armenia and thanks for your presentation. You mentioned that transitional justice has 4 components - Justice, Truth, Reparations and Institutional Reforms. Here, Truth Committees are the ones who tell the story and who shape public opinion telling things as they happened. Who is included in these Truth Committees, who tells the story? Is it a public effort, a state effort, or a combination of the two?

Dr. Bernaz - It depends on the commissions. In every process like this there are discussions on who will get to talk and participate, because even though the processes are wider and less structured than prosecutions, u still need some form of organizing and structure. Going back to Pr. Shabas’ experience in Sierra Leone, where tens of thousands of people were tortured and killed, horrendous crimes were committed, people lost their homes, their children, women were raped etc., however not every survivor will get to tell their story, you have to manage expectations and decide that only a few people will be allowed.

There will be a lot of people but if you don’t want to give just 30 seconds per person and still want to tell a story representative of what others have gone through, you have to make choices. Participants to The Truth Commissions are basically everyone who either was a perpetrator (like in South African experience where perpetrators told the whole truth in exchange for amnesty) or victims, also past and current public authorities can participate. Depending on what subject is considered you can have lots of different stakeholders. This raises another issue - do you only listen to what community leaders have to say? In this case women are ignored because community leaders are mostly men, so there are a lot of issues involved and there are pretty sophisticated frameworks on how to make proper decisions. But no matter what decision is made you have to understand that you cannot manage to listen to everyone. There is a need to keep balance between listening to leaders, who may have more knowledge, and listening to people involved in all levels.

Q - I see there is the problematic issue of representation involved in this. If we are telling the story, then who is telling the story, and if someone is speaking on behalf of others then we may face this issue, especially in such a delicate process as Transitional Justice.

Dr. Bernaz - True, and I think that you should say that you are telling a story hoping that it tells the story. In fact, there are debates in the academics between historians and lawyers like me and those who specialize in transitional justice processes. When you say that this is telling the truth and this is how we are going to tell the story in the future and this is what is going to shape the narrative - historians are going to disagree with that and say that with one story, which necessarily has its own biases, you cannot say that that’s the truth. I wouldn’t dismiss the whole thing just based on this opinion, there is still value in doing it, because if you wait for the perfect moment and scenario then eventually you end up not doing it.

Q - You talked about the importance of holding corporations, businesses and the private sector accountable for their involvement and for the crimes that they have committed. There are oligarchs in Armenia. People know about them and know stories of crimes connected directly to them or their circles. We know about their luxurious lifestyles and we can say that these oligarchs have, in a way, become corporations themselves. How can those people who have suffered (in many different ways) because of these oligarchs be personally involved in the process of holding them accountable?

Dr. Bernaz - If the role of The Truth Committee has been taken then these people have to be heard in some way. They can be involved in prosecutions as victims, witnesses or they can be empowered with some role so that they will be able to tell their story. There is also value in discussing these issues in public spaces. Engaging some people who have spoken up can empower others to speak up as well. It is not necessarily about being heard individually but feeling that your leaders care about your story and that it is important to them.

Q - Let’s talk a little bit about political “stability” and Transitional Justice. In their speeches our prime minister, deputy ministers and the head of Yelk Faction in the parliament have placed an emphasis on not scaring potential investors, noting that in order to attract large investments we need political stability. How do these relate?

Dr. Bernaz - I think in order to escape that “one or the other scenario”, it is important to rephrase the message to the outside world and to foreign investors. Instead of saying that from now on we are going to have this radical agenda and you are going to have to live with it now and if you are not happy you can go, it is better to say that what we are trying to do here is bring stability and rule of law, there are international frameworks, we think human rights are important, corruption is an issue, we are making these changes that are necessary and your assets will be safer when we do it. And yes, this means that things that were allowed before will not continue and it the long run this is good for the stability of the country. Also, bear in mind that there will always be investors who will be scared by the change and who will go away, and some corporations will pull out. But other investors who value the stability of country that is abided by the rule of law, that is under the umbrella of European Court of Human Rights will come. I think it is more likely that companies will invest in countries with stable democracies than countries which are completely out of control.

Q - If we open up our doors to this free flow of global capital and claim that the state is doing everything to protect their investments, doesn’t this also raise the issue of Armenia becoming a place where corporations can come and do whatever they want to.

Dr. Bernaz - There is a trend in investment law that more and more investment treaties and contracts mention labor and human rights issues as something that parties to the contract need to pay special attention to. And there are precedents for this as some kind of a new development in this area.

Q - So what you mean is that it is possible to include, let’s say, labor rights and other human rights stipulations into the individual contracts with corporations, thus informing them from the outset that they will have to adhere to various rules and regulations.

Dr. Bernaz - Yes, you can do that, and some have done that. There are two sides to this. First, there are liberties that some of the corporations have taken to include in contracts and accept that certain things won’t be the norm anymore and things have changed.

Second, it’s about the state admitting that it has human rights obligations and it might use legislation to strengthen human rights protection in the future. This is something that has caused a lot of issues in investment arbitration where states didn’t have strong mechanisms for protection of human rights. For example, in Argentina the government wanted to guarantee access to water for its poorest population and so they legislated to force private companies to supply water to these poor people. Those companies said Argentina was breaking investment contract because initially they didn’t have any obligation of providing water to the poorest people.

So, these companies sued Argentina and Argentina lost. Also, these companies were under the impression that the environment was never going to change and the country that had human rights agenda, in this case Argentina with its need to provide equal access to water, was punished. From fear of losing multi-million-dollar cases countries become hesitant to change their laws. You cannot do much about existing contracts, but you can think of such issues in the long run and show the investors the environment and standards in which they are going to have to operate. I bet a lot of companies will come any way.

Q - What is the connection between asset recovery and social justice? In your presentation you have mentioned that for asset recovery countries need to implement high standard criminal prosecutions, which may take years. In this case how can we put asset recovery in the framework of social justice and when does social justice step in, because asset recovery is not solely about lengthy high standard criminal prosecutions but also justice in a broader understanding of the word.

Dr. Bernaz - Frankly, I cannot answer this question. The idea is that it is not just about tracking the money but also about looking forward - that’s is the big thing. The difference between normal prosecutions and transitional justice mechanisms, including prosecutions, in this context is that prosecutions, generally go/look backwards and by implementing transitional justice you look forward, you look at the future. So where does social justice come in - I do not know.

But certainly, it should come in. And also, for me, it is a very practical reason to include corporations in transitional justice because they tend to have more money than individuals. So, by involving those it is possible to recover more money than to prosecute a corrupt politician. In terms of social justice, those mechanisms include corporations “contributing” in some way. Though I have my reservations any time money is being handled. There’s an example from Cote D’Ivoire where a big company dumped polluted material and as a result, tens of thousands of people became sick, some people died. In the end the case was settled in The High Court of Justice in London and that means there was no judgement. The company paid an amount of money, probably millions, we do not know how much because the settlement was secret, and then many cheered about how great it was from responsibility point of view. But the reality is that a research that was conducted afterwards showed how this money was misused and as a result so many people who suffered from pollution never saw any money or help.

What companies do in Africa they would never do in Europe, they went there because these people were disempowered, because these people are poor, and their government is not protecting them. So, coming back to your question - I am always suspicious about these big trust funds because the potential for mismanagement of the money is too high and it throws shadow to the whole process which is a real shame. Prohibiting companies from bidding for public contracts is a good mechanism for holding them accountable. This is, of course, about looking forward, it won’t let you recover all the assets, but at least you will know that companies who bid for contracts are not those that have been involved in corruption and dodgy things in the past.

Q - The state is the main guarantor of the implementation of transitional justice - this new government that comes after revolution and starts making changes. We have the situation when there are still people - middle level state officials and others who have benefitted from the corruption practices before and they still continue working. There are old people in the new context and there is the willingness of the new government to implement transitional justice. Does this situation contradict the idea of transitional justice?

Dr. Bernaz - This is common, especially in small countries you cannot change everyone. You need the expertise you need the people. Surely, these people played their role, but they also know how things are done and they have their connections. You cannot just put new people everywhere because how are you going to find so many people?

I liked the point about Armenian Diaspora. You could say that you are going to take only those who haven’t lived in Armenia for several years but that is problematic - will people here accept that? I do not think they should. Also, the good thing about softer transitional mechanisms (rather than prosecution) is that they allow to take on board people who are neither very enthusiastic nor completely opposed. And what I mean by that is in every large organization, like the government, there is always people who just went along with it, not everyone has principles and not everyone has strong ideas about justice. These people wanted to have a comfortable life and you could say that they were all corrupt, but they can be turned, and that is the experience of other countries.

From one side there is a group of people who just won’t turn, there is the group who really are leading and there are also these people we talked about who with the right leadership will go forward. That is why leadership is so important. You cannot have a repressive approach because with it you are going to scare these mid-ranking officials, who in the grand scheme of things, are not that responsible. They are not perfect individuals but presented with an opportunity to do better for their country with the right narrative they will take that opportunity. It is extremely difficult to do, but there is no good alternative to that.

Q - You and other panelists have spoken about the lack of resources for implementing transitional justice and, ironically, this issue comes up in a situation when countries are trying to hold corporations accountable for their crimes but do not have enough resources for that because corporations have most of the resources.

Dr. Bernaz - That’s really is an issue in my area, where I look at litigation by poor communities around the world who are trying to take on some of the richest corporations like oil companies. The only way to address this imbalance is to device a judicial system that allows claims from disadvantaged communities by providing legal aid. It is a big problem that cannot be solved, it’s capitalism - this inequality of arms, this inequality of power.

You can devise ways to try to address it, in a way that European Convention on Human Rights does with its article of fair trial and all other articles that address this issue. But at the end of the day it is a fact that there are corporations that can pay their lawyers 2000$ an hour whereas that’s what people make in a year. However, things are changing in this area, there are more and more discussions about big transnational cases, victims in developing countries and big corporation in The Global North and more discussions about litigating those cases showing what can be done. It is changing a little bit.

You can watch Dr. Bernaz’s full presentation here.

Follow Dr. Bernaz’s on Twitter.

Follow Hetq and Samson Martirosyan on Twitter.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment