Freedom of News Outlets in Armenia

(January-October 2013)

Ara Ghazaryan, Ashot Vareljyan

Insult and slander court cases against news outlets

a) Statistics

From January to October 2013, thirteen legal suits accusing new outlets or reporters for slander and insult were filed with the courts. Six of these were repeat cases filed by the same individual against news outlets with the same set of charges and facts.[1]

Three of the thirteen trials have ended, and the others are on-going, either in the Court of First Instance or the Appeals Court. Overall, from decriminalization May 2010) until the writing of this study (October 2013), 73 suits have been filed against reporters and news outlets. Fourteen are still in the courts[2]; the other 59 have been completed.[3]

Legal decisions have yet to be handed down in ten of the fourteen ongoing cases. At least one verdict has been issued in the other four.

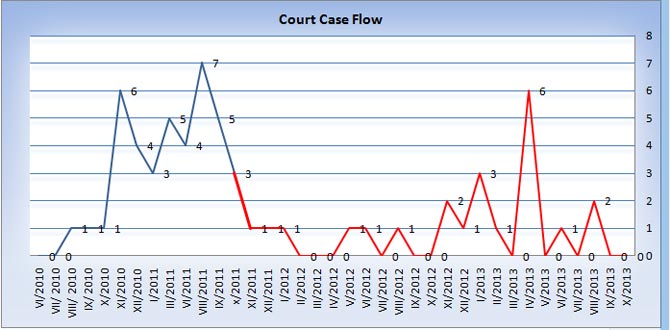

The charts below depict the breakdown of cases since decriminalization over time.

Table 1. Court case flow per months

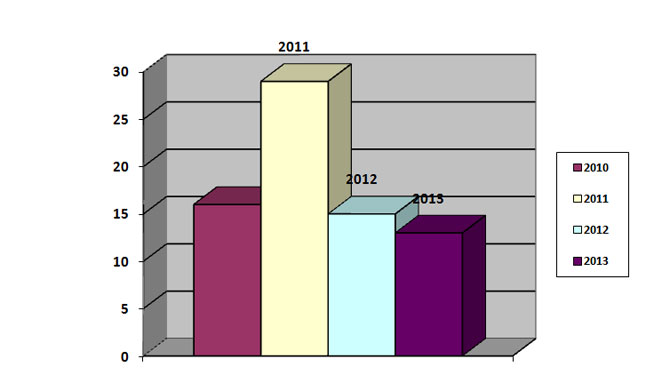

The blue line covers the time period until the Constitutional Court handed down its famous Decision 911 (November 2011). The red line depicts court cases after this decision. As we see, the number of cases significantly dropped after this decision was issued – from one to two cases per month. This rate continues to date. The reason for the jump to six cases in April 2013 was due to the fact that the same person filed all six suits against six news outlets; all based on the same legal arguments. Thus, if we regard the six cases as one, the monthly rate falls back within the zero to two average. This is also evidenced by the yearly breakdown of cases. From July to December 2010, 16 cases entered the courts, 29 in 2011, 15 in 2012, and 13 from January to October 2013, of which six are repeat cases filed by the same individual.

Table 2. Number of court cases per year

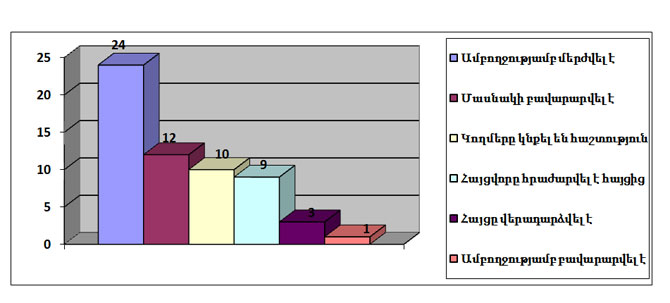

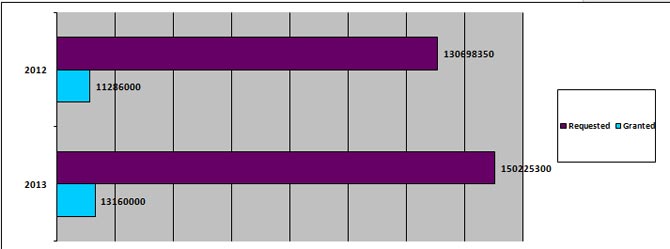

Of the 59 completed cases, 24 (41%) were completely rejected by the courts. Twelve (20%) were partially sustained. A reconciliation agreement was reached in ten (17%). The plaintiff withdrew the suit in nine cases, and the courts returned the suits in three cases, so that corrections could be made for re-filing. The courts completely sustained the plaintiff’s suit in only one case.[4] (See Chart 3) In the 59 completed cases, a total of 150,225,300 AMD was sought in compensatory damages against news outlets and reporters. Of this amount, 13,160,000 (8.7%) was sustained. Noteworthy is the fact that as of October 2012, this figure was 8.6%. In the 36 cases that had been completed as of then, a total of 130,698,350 AMD had been sought in damages, but only 11,286,000 (8.6%) had been allowed. (See Chart 4)

Table 3. Court decisions [PU1] [A2]

Table 4. Comparative view of monetory compensation claims as of October 2012 and Ocrober 2013

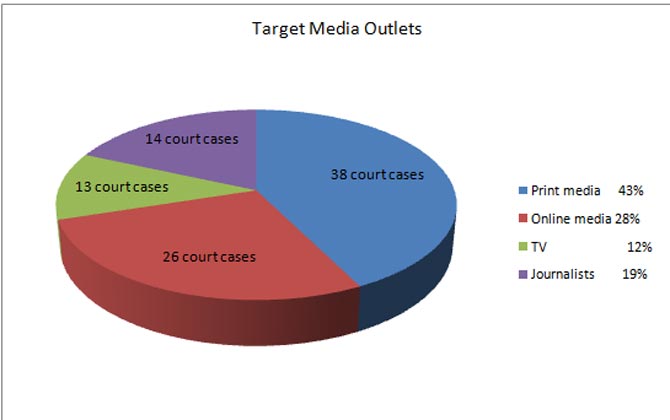

Comparatively more legal suits have been filed against print news outlets – 38 (37 newspapers and 1 magazine. Next in line were internet sites – 26; followed by reporters – 14; TV – 13. Sometimes suits were filed against both news outlets and reporters (See Chart 5).

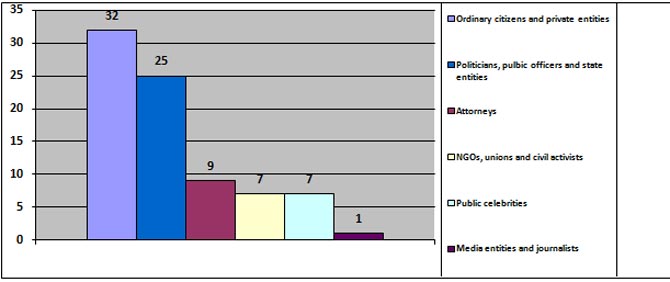

Comparatively more suits were filed by ordinary citizens and private companies (32), as opposed to by politicians or state officials (25). Suits filed by attorneys are also increasing. Even though the study notes 9 such cases, in reality, 3 attorneys have filed suits to date, two of which were filed against several news outlets (See Chart 6).

Table 5. Number of court cases against each type of media outlets

Table 6. Number of court cases per groups of applicants

The above breakdown shows that the 2012 trends are generally being maintained. The low number of court cases (1 or 2 monthly), is maintained. Most are rejected, either wholly or partially. Often, the courts partially sustain the plaintiff’s demands, while in general, the number of cases are resolved via a desire of the parties to reconcile is growing. There is a relatively large number of cases in which the plaintiff withdraws his/her suit in the examination phase. These trends can be explained by the fact that the courts have set the bar quite high in terms of evidence for plaintiffs, thus allowing a markedly greater degree of defense for news outlets, reporters, and freedom of speech.

2. Content analysis of court decisions

During January-October 2013, the courts have issued mostly favorable verdicts regarding the freedoms of news outlets and reporters. At the same time, the courts have also issued questionable verdicts in certain cases.

In early 2013, a decision handed down by Yerevan’s Kentron and Nork-Marash General Court of Jurisdiction, calling for a freeze to be placed on 3 million AMD worth of property owned by the daily newspaper Zhoghovourd, caused an outcry in many circles. In the case, the newspaper was sued by the Yerevan Poultry Factory and its director, Khachik Khachatryan. The court issued the freeze allegedly as a measure to guarantee that the paper would be able to pay compensation to the plaintiffs if they won. The newspaper and certain legal rights defenders regarded the court’s decision as a lopsided approach to a news outlet’s right to freedom of expression, in that the freeze threatened the very operation of the newspaper. In this regard, a clarification was sounded by the judicial authorities and certain organizations involved in news outlet self-regulation, saying that the court’s decision, in general, was proportionate, given that the freeze was only placed on property and not financial resources. Thus, they argued, the operation of the newspaper wasn’t threatened. Truly, the placing of a freeze in this case was a proportion manner of intervention, as was evidenced by the fact that the newspaper continued to operate unrestricted despite the freeze. This method has become standard practice today. When the courts receive a freeze motion by the plaintiff, they prefer to place a freeze on property and not on financial or other resources, thus allowing the news outlet to operate normally. Thus, the courts ensure the free flow of information by the news outlet during the trial.

In 2013, the courts were again forced to pay attention to an essential shortcoming in the law; i.e. the inability to mount a legal defense against non-public insult and slander statements. The reason is that Article 1087.1 of the Civil Code only allows a defense against publicly disseminated speech.

This issue first came to the fore when Armenian MP Ruben Hayapetyan insulted Hetq reporter Grisha Balasanyan during a telephone conversation. The issue was also discussed as a result of a similar case involving Zhoghovourd newspaper reporter Sona Grigoryan. She sued Yerevan Poultry Factory Director Khachik Khachatryan in civil court, claiming that he had insulted her over the phone. The court was forced to drop the case, since the plaintiff’s rights to a defense weren’t covered by Civil Code Article 1087.1 or any other clause. Taking up the issue, the Information Disputes Council in its Decision #32 noted that there was a gap in the system allowing for a violation of Article 19 of the Constitution – the right to a fair and independent legal defense. In this regard, it must be noted that the Constitutional Court, in its Decision 997, had already expressed the view that, “it is not a shortcoming of said article of the Code, but an overall legal-regulatory shortcoming, and to overcome it the Armenian National Assembly must, within the scope of its jurisdiction, raise the issue of defending against non-public defamation as a separate topic of discussion.” Two years have passed since the Constitutional Court issued this decision, but the National Assembly has yet to implement it.

The courts continue to receive legal suits in which plaintiffs argue that news outlets have violated the “presumption of innocence” principle when covering trials or pre-trial examinations. Such suits, as a rule, are brought under the rubric of Civil Code Article 1087.1, which regulates the legal aspects of insult and defamation. However, this article does not provide effective defense mechanisms when it comes to litigating violations of the presumption of innocence in civil-legal relations. As a rule, the courts reject such legal suits, noting that the presumption of innocence is a criminal-judicial category, and as such, does not fall under the domain of a civil right. In fact, the Civil Code does not delineate the possibility of filing a civil suit regarding a violation of the presumption of innocence principle. In this case, the method to mounting a legal defense is fully absent. This is the reason that citizens are forced to litigate such violation cases on the grounds of insult or defamation which, as has been noted, is an effective legal mechanism for this legal relation.

For example, the Shirak Provincial Court is now hearing the case of Haroutyun Sargsyan v Tsayg TV. The plaintiff claims that the TV station insulted and defamed him by accusing him of a murder before being found guilty by the courts. If the pre-trial examination continues until such a time when Sargsyan is actually accused of murder, then the news outlet won’t be held liable since the information it had disseminated proved to be correct, and not slander. However, Sargsyan’s right to a “resumption of innocence” has nevertheless been violated all the same, regardless of whether or not he’s charged with murder at a later date. But if Sargsyan were to file a suit in civil court, claiming that this right of his has been violated, the court would throw it out, given that he is arguing a right not covered by the law. We believe that such a situation is a system-wide shortcoming in the law that needs to be addressed. It’s a fact that today the presumption of innocence is violated to a greater degree in civil-legal relations, than in the criminal-judicial process. For example, we can cite those media outlets, particulary, journalists who work in the style of paparazzi and aren’t concerned with the possibility of being punished for violating the presumption of innocene, given that as yet they haven’t been sued for such infractions. In other words, the violation of the presumption of innocence exits in social relations, whereas a legal defense against such a manifestation is lacking. This state of affairs raises a constitutional issue.

Troubling was the decision of the Shirak Provincial Court in the case of Hambardzum Matevosyan, in which the judge, after approving the reconciliation agreement between the parties, obliged Hetq Online (neither a litigant in the trial or reconciliation) to publish a retraction. Experts say this was an inappropriate court intervention on the news outlet. If the court decided to obligate the news outlet to publish a retraction, than the court first should have made the news outlet a party in the court case, so that the outlet could have the opportunity to argue against such intervention. On the other hand, the news outlet isn’t deprived of the opportunity to appeal this decision by the court, which it has done, even though its appeals were rejected as baseless. In addition, if the news outlet has a conflict with the person who demanded that it print a retraction in the first place, it can petition the courts and challenge the obligation placed on it. The question thus arises – does such a judicial opportunity undermine the legality of the original demand placed on the news outlet (the court defining an obligation on the news outlet during a trial it didn’t participate in). We do not think so, since in all cases, the news outlet must first implement a court verdict that has legal power, and the implementation of that verdict cannot be halted on the grounds that the news outlet has entered into a separate court case with the individual who presented the demand that the news outlet publish a retraction. To date, we know of one other such case where the courts have placed an obligation on a news outlet in a court case in which the outlet hasn’t been a litigant. Such court decisions are ones that interfere with the rights of news outlets and we hope that such decisions don’t become judicial practice.

In the case of Armen Darbinyan v Civic Investigations Center Ltd.,[5] the court expressed several important positions regarding the term “judgment” in the concept of “evaluative judgment”.[6] An approach had taken shape in domestic state judicial practice, whereby litigants would attempt to present common statements as evaluative judgment, just as tactical ploys. Sometimes, even the courts present declarations of fact, including common opinion, as evaluative judgment. [7]

In this context, the necessity for judicial interpretation of the term “evaluative judgment” had arisen in practice, which was given in said court case, clarifying the issue of applying the term. Nevertheless, we believe that the issue partially lies in a defect of the legislation, since the main regulatory norm (Article 1087.1 of the Civil Code), does not provide a independent definition of the “evaluative judgment” concept. Instead, in the article, the legislature uses the term public “expression”, which equally refers to statements of fact and evaluative-judgment. In legal practice this leads to confusion. Even though the courts continuously broach this concept in their decisions, due to the lack of legislative regulation, situations sometimes arise when litigants perceive statements of fact as evaluative judgment, and vice versa. As a result, courts sometimes demand that litigants prove a statement that objectively cannot be proven. For example, in the above-mentioned case, the defendant was asked to prove the validity of the expression “Napoleon-like phenomenon”, which cannot be objectively proven and it not subject to proof in a legal sense.[8]

Another case was Women’s Resource Center NGO v Zaruhie Publishers Ltd., in which the court demanded that the plaintiff prove the veracity of the expression “home wreckers”, and then concluded in its verdict that the author of the article, “did not note, nor could it note in court, any evidence that any direct activities of the plaintiff had caused the destruction of even one family.” Whereas, the court should have taken into account the fact that the author, by using this expression, had provided a value judgment regarding the activities of the organization[9], and not specific evidence as to the destruction of families. It was an opinion, an evaluation based on the individual’s subjective impression, which isn’t open to being proven. In such situations, defining the burden of proof is regarded as a disproportionate restriction on the right of freedom of expression. In the same case, however, the Appeals Court expressed a position possessing a positive inclination. In this case, the State Language Inspectorate officially expressed an opinion regarding the term “grant sucker”, noting that the word has a negative connotation. The Appeals Court, as a result of a judicial check, stated that if it was possible to accept the conclusion of the Ministry of Education and Science’s Language Inspectorate regarding the composition of the word, what was unacceptable was its opinion that the word had a negative connotation. According to the Appeals Court – “Giving an evaluation as to whether the expression is insulting or not is reserved to the court, and not the Language Inspectorate.” Such an approach is to be welcomed since in cases of insult or slander it is very important for the word to be interpreted in the context of a public statement, and not out of context, whereas a state body, contrary to the court, is inclined in all cases to interpret the meaning of the word in an abstract fashion. In addition, in this case the state body reserved the functions of the court to itself, which is unacceptable.

Along these lines, the conclusion of the judicial tribunals regarding the court expenses in the case of Ijevan Road Construction v Ijevan Studio Ltd. and reporter Nayira Khachikyan was very troubling. The Court of First Instance completely rejected the demands of the plaintiff, but at the same time obligated the defendants, in case they lost, to compensate the plaintiff 100,000 for hiring a lawyer, and to pay 40,000 in state fees. The court justified this apparently strange approach by arguing that even if the Court of First Instance had rejected the claim that insult had been levied, however, it did accept the evidence of slander. Thus, it was this portion of the suit on which the court granted the plaintiff’s demand for compensation of legal fees and the state fee. As to why the court didn’t state this in the verdict summary, the Appeals Court argued that in reality it had also rejected the slander portion of the suit, but not on material-legal grounds, but solely based on the financial situation of the TV station and the reporter.

The conclusion reached by the courts in this case caused uncertainty in press and legal defense circles. In the end, even if a news outlet wins its case in the courts, it still isn’t free form the obligation of paying compensation. What inhibited the court from clearly stating in the verdict summary that the news outlet had violated the plaintiff company’s rights as to slander and to register the violation, while at the same time rejecting the financial demand?

According to the Information Disputes Council - “The noted approach of the court is problematic as it can create chilling effects on the freedom of the media and journalists in light of the above-mentioned principle of Article 19. If this decision becomes widely practiced, even in the case of winning a case, the journalists having found themselves in the situation of the respondent might be obliged to pay high monetary compensation, which will make any legal remedy null and void, and seriously endanger free speech. Taking into account the importance of the freedom of the media in a democratic society, the Council expects that the Civil Court of Appeal will revoke the afore-mentioned decision”.

The court rejected the first of six suits brought by Karineh Avanesyan on the grounds of late filing. The process is noteworthy given that the first instance court once again interpreted the deadline rule - “one month after the moment of being informed and six months from the date of publication” - for filing slander and insult cases. The court noted that the second element takes precedence in all cases. Regardless as to when the individual is informed about the publication, the six month deadline takes precedence. In the same case, the court also interpreted the maintenance of the mentioned deadline in order to substantiate the conception of presented “evidence”; by applying the precedent setting definitions of the Court of Cassation.

In particular, the court specified that the maintenance of the six month deadline can be substantiated with indirect evidence, and that the suit cannot be rejected solely on the grounds that the presented evidence is not direct evidence. It becomes clear from this judicial decision that today, that a constant precedent setting law has taken shape regarding the issue of regulating expiration deadlines in slander and insult cases.

A number of other decisions have been taken in this period in which despite the fact that nothing new has been registered in court practice regarding the issue of the law, the courts, however, have consistently rejected groundless complaints presented against news outlets and reporters.

[1] The suits were filed by former attorney Karineh Avanesyan, who was found guilty and is currently imprisoned for forging a unfavorable legal deed for her defendant. She filed suits against six news outlets, arguing that by publishing a statement about her guilt during the trial, they insulted and slandered her. The courts, in two decisions, found the plaintiff filed the suits after the six month deadline.

[2] During the same period last year, 15 of the 51 cases were ongoing; about the same amount as in 21013. This is also evidenced by the monthly breakdown of cases presented, which fluctuates between zero and two; an average of one case per month.

[3] The study does not cover court cases in which news outlets or reporters are included as third parties. In our opinion, inclusion as a third part litigant does not constitute essential interference. Thus, we haven’t covered them here.

[4] See the civil suit (ԵԿԴ/2347/02/10) filed by National Assembly deputies Samvel Aleksanyan, Ruben Hayrapetyan and Levon Sargsyan against Dareskizb Ltd.

[5] See Civil Case ԵԿԴ/2050/02/12.

[6] See ՏՎԽ Decision 12 – Glendale Hills v Zhamanak newspaper.

[7] See, for example, the verdicts of 27/04/2012 and 22/03/2013 by the Tavoush Provincial Court in case ՏԴ1-0177/02 (Ijevan Road Construction v Ijevan TV and reporter Nayira Khachikyan), in which the court presents statement of fact common statements or expressed views as evaluative judgment.

[8] An analysis of a similar situation was made by the European Court in the verdict of Novaya Gazeta ve Voronezhe v Russia (No. 27570/03, 21/12/2010, § 52).

[9]The Women’s Resource Center deals with family violence and gender discrimination issues.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment