Revenge of the French-Armenians: The 1956 Visit of French Foreign Minister Pineau to Yerevan (Part 1)

By Gevorg Mkrtchyan, researcher at Factum NGO

The first page of the May 16, 1956, edition of Sovetakan Hayastan (Soviet Armenia), the official newspaper of the Communist Party of Armenia, largely focused on the release published by the Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS) regarding the visit of the French prime minister and government members to Moscow.

The publication, featuring the headline “The Visit of French Prime Minister Guy Mollet and Foreign Minister Christian Pineau”, does not say much at first sight. The French officials arrived, Soviet leaders met them, then they exchanged compliments, and spoke about improving relations between the two countries.

At the Moscow airport, the French PM said that Foreign Minister Christian Pineau was planning to visit other regions in the USSR to get an overall picture of life in the Soviet Union. “That’s what international relations should be built on – on real facts – and not on theoretical conclusions the misapplication of which has often been detrimental,” the article quotes French PM Guy Mollet.

Among other cities, Pineau visited Yerevan. However, it would not be right to say that the visit was highly important. Prior to his visit, other foreign officials also used to visit Armenia, travel by the Sevan-Garni-Geghard-Etchmiadzin route, and meet the Catholicos of All Armenians, make notes in the Matenadaran Memory Book of Guests and leave.

Pineau’s “appearance” in Armenia was different. It was different not only in the content, but also in the way the high-ranking official was greeted and met – it was the testing of the situation that had emerged after the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union as well as the relative freedoms that had “evolved” in that very situation.

After learning about Pineau’s upcoming visit to Yerevan (you could learn about it only if you were secretly listening to foreign radio), repatriates from France seriously prepared for it.

First, we will briefly introduce the repatriation story of French Armenians.

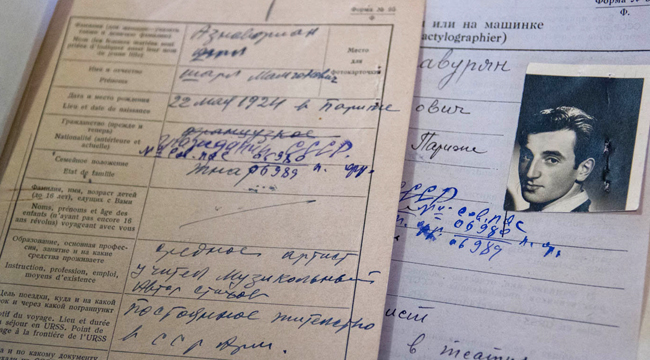

French-Armenians, around 5,000, immigrated to Armenia in two waves – in late 1947 and early 1948. Many Armenians in France strived to repatriate to Armenia, even world-known singer Charles Aznavour’s family was among them – their application is kept in the National Archive of Armenia. The organizers of the migration, however, did not get other caravans of people moving to Armenia and quite a large group of French Armenians lost their right to resettle in their motherland.

The 5,000 repatriates from France enjoyed, so to say, relatively privileged terms than those that had immigrated to Armenia from the Middle East, Eastern Europe or Iran. U.S. Armenians were the next to enjoy such “privileges.” Our studies have shown that six of the 350 repatriate families that were exiled on June 14, 1949, were French Armenians. No U.S. Armenian family was exiled.

It’s accounted by two factors. First off, at the end of the day, the repatriation of Armenians had turned into the USSR’s and Stalin’s personal “PR campaign”. Look how nice we are, tens of thousands of people aspire to flock to the Soviet countries “to live under the Stalin flag.” (The quote marked in inverted commas is taken from repatriates’ letters.) Thus, we believe the care authorities were displaying towards these groups of immigrants was accounted for by the wish not to provoke the West (the U.S., France) – a former ally that was gradually turning into an enemy after World War 2.

|

|

The second, more objective reason, deals with prior immigration groundwork carried out in those Armenian communities and the feelings over it. Unlike other communities, there was no all-embracing excitement in France and the U.S., and inter-community life was rather polarized. While hundreds of people in the Middle East or Iran were quitting the Dashnaktsutyun (ARF) to repatriate, the number of such people was very low and even non-existent in France and the U.S.

Dashnaktsutyun was trying to hinder repatriation. Touching upon the measures taken by local members of the Dashnaktsutyun to thwart repatriation, third secretary of the USSR Embassy in France, Inaekian, wrote in his report that “there are rumors that the possessions of the immigrants are being confiscated upon their arrival at the Soviet Union, and instead of Armenia, most immigrants are being sent to Northern Caucasus or Ingushetia.” Inaekian was accusing the National Front, the organizer of the immigration, of not giving adequate response to Dashnak Party members.

|

|

(Famous French-Armenian caricaturist |

People filled with and sharing either patriotic or Marxist and socialist ideologies and whose biography barely contained “past sins” were the ones that used to apply to repatriate from France and the U.S.

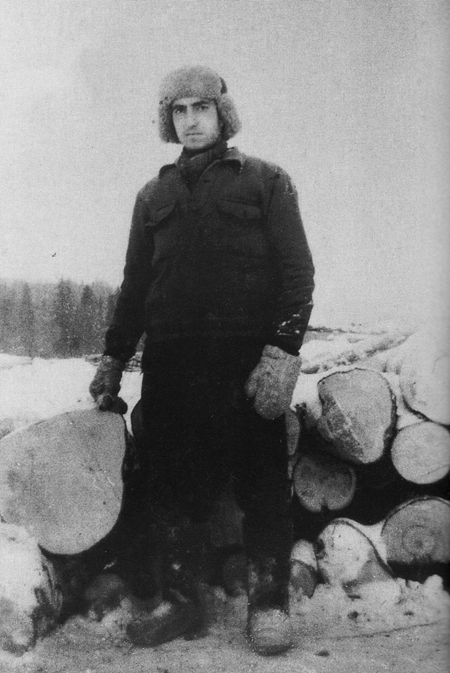

Overall, besides the abovementioned six exiled families, 53 French-Armenians were subject to violence during the Stalin era and were sentenced to prison, mostly for their attempts to escape.

|

| Լիդիան մոր հետ, Երեւան, 1948 |

As seen from the 25 interviews held in Paris, Marseille, Lyon, and Valence, besides fear from Stalinism and the dreadful prospect of being sentenced and exiled, French-Armenians had other reasons for discontent. Among those reasons, the incompatibility of Soviet life, lifestyle, routine and culture with their memories was one of the most significant reasons.

Lydia Kyureghyan, who immigrated in 1947 and presently resides in Paris, says that oriental (eastern) behavior and demeanor are what she detested most. “If a girl was not a virgin, she was not accepted. If the woman was infertile or couldn’t have a baby, she was being “returned” to her parents’ home. If there was a man who wanted to marry a [beautiful] girl who didn’t like him, he would kidnap her. I deemed such conduct wrong and never accepted it.”

Robert Ananikyan, who repatriated from France in 1947 and presently lives in Paris, remembers how his mother’s charitable act was thwarted. “We used to live in Kirza. It was a cold winter with heavy snow. I had shoes but most of my friends didn’t. I used to go to their places and ride them to school on my back. My mom said ‘this can’t go on forever. I should organize gatherings and charge entrance fees. The fees will range from one to three rubles – everybody will pay as much as they can afford.’ Her goal was to buy shoes and clothes for those who didn’t have them. The head of our school called my mom in and said that since the gathering was being held in his school, she should share half of the raised money. Apparently, she didn’t do that. And my mom’s charitable act resulted in that charges were pressed against her and all that created lots of fuss and noise.”

There is a myriad of such stories that speak of the clash of “civilizations” and perhaps precisely that conflict was what pushed French-Armenians to meet Christian Pineau.

(to be continued)

Translator Ani Babayan

This article is prepared as part of the “Two Lives: The Cold War and the Emigration of Armenians” project financed by National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment