Artsakh Childhood: Bartering Toys for Bullets

“Even Avo said let the boy fight”

Grigor Hakobyan was only 12 when his family fled Baku in 1988 to the safety of the Russian city of Pyatigorsk where they had relatives. One year later they resettled in Martouni, Karabakh.

When Grigor turned 15, he had to take care of his sick father who was bedridden. Grigor’s mother would spend days on end working at the hospital to make end meet.

“After a while, Grigor told me that he could no longer stay at home, like a girl, and take care of his father. He said he had decided to go to the front and defend the land like the other men,” recounts Grigor’s mother Mrs. Ofelya.

Grigor decides to defend frontlines

Grigor’s decision stunned her. She knew that her son was deadly afraid of the sound of gunshots. When the town was being fired upon, Grigor would jump out of bed and run, naked and shoeless, to the basement of the police station.

“Our home was like a battlefield. The neighbors tried to convince Grigor that he was too young to go off and that he was an only son. He locked himself in his room and wouldn’t eat for three days. We could only speak to him from the window. But that’s not all. We had a meat knife. He took it and threatened to kill himself if I didn’t let him go,” says Mrs. Ofelya, adding that Grigor took that knife with him into battle.

The mother was at her wit’s end. She even sought out Avo (Monte Melkonian) for advice. She was shocked to hear Avo say that Grigor had made the right decision. Mrs. Ofelya reluctantly gave in, telling Grigor that he could go if his duty tour came up. I hoped that if he saw the real face of war, he would back out,” she says.

Goes off to war in school clothes

Grigor’s inner will was more than his relatives had imagined or bargained for. In 1992, wearing his white school shirt and gym pants, Grigor sent off for the Moughalou front. Several days later, he had gotten his hands on some army clothes. Grigor and the others would go to the front every evening and return the following morning.

“He wanted me to have hot water ready and a bowl of sunflower seeds when he came to the house. Boys will be boys, I guess. He didn’t talk much. He had the same answer to all my questions – Ma, everything’s OK. Don’t worry. We are out of gunshot range,” recounts Mrs. Ofelya.

The mother confesses that her son’s words buoyed her spirits, even though her unease remained. Grigor went to the front for the next four months. On June 4, 1992, he went to the frontline as usual. Out of a group of eleven guys, seven made the trip that eventful day.

It was like he was saying goodbye

“”Before leaving that day, they had gone shopping for provisions with the unit commander. When he learnt that some of the men wouldn’t be going, the commander said that he would take their shares to the house so that his wife would have something to cook a nice meal when the unit returned. I was working in the garden that day. I looked up and all I could see was my son’s head as they hurried off. I figured he didn’t want to pull me away from my work. As he sped off, he looked back long and hard at me and the house. It was like he was saying good-bye for the last time,” says Grigor’s mother.

She says that the men had built a fire where they were bivouacked that day. This caught the attention of the enemy. They advanced and attacked with hand grenades. Two of the Armenians were killed immediately in the trenches. The others fled. Grigor’s buddies had told him to make tracks for Artzvik if they had to retreat.

Grigor never made it. He was shot once in the head and once in the abdomen. The enemy stripped him of his uniform and ammo, cut off his ear, and left him to slowly die.

“When we heard about what had happened, a truck was sent to collect the bodies. But the truck had an accident and by the time it arrived, Grigor had died. Later, the doctor said Grigor might have pulled through had we reached him in time. Yes, he might have been disabled, but he would be alive and sitting next to me today,” said a distraught Mrs. Ofelya.

Grigor returns in her dreams

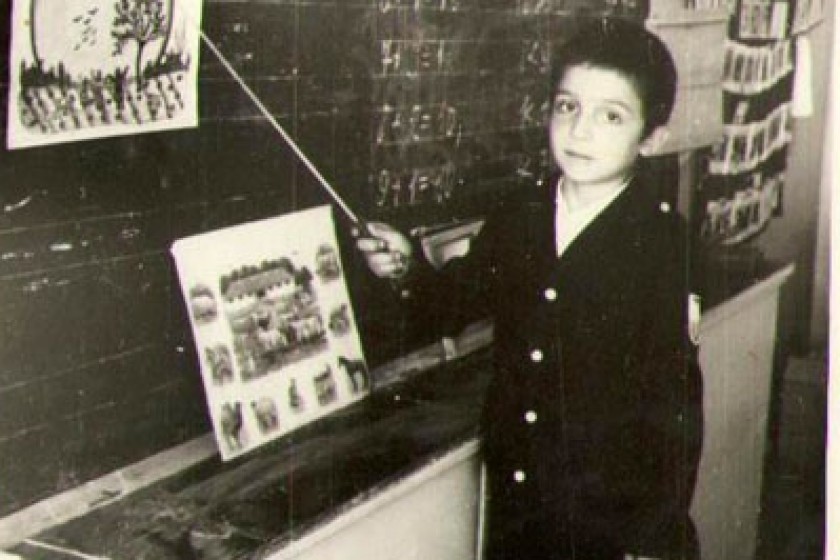

Mrs. Ofelya confided that at one point she decided to sell the house and leave Karabakh. So unbearable was the loss of her only son. She says Grigor never let her do so; nightly he visited his mother in her dreams. Today, she lives with the memories of her only son. A photo album provides temporary solace. Turning it pages, she lightly caresses Grigor’s only baby picture.

“When we came from Baku, we brought a lot of toys with us. Later on, I noticed that all these toys were strangely disappearing; one after another. I asked Grigor, but he said he didn’t have a clue. I solved this riddle only after his death. Down in the basement I found several small boxes neatly filled with bullets of various calibers. It turns out Grigor had bartered those toys for bullets,” recounts Mrs. Ofelya.

In 2007, Grigor Hakobyan was posthumously awarded the Medal of Courage. After years of battling with the bureaucracy, Mrs. Ofelya finally got the government to renovate her house.

She says that while it’s now clean and comfy, it’s missing one irreplaceable thing – her son’s presence, her son’s smile.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment