Between War and Peace

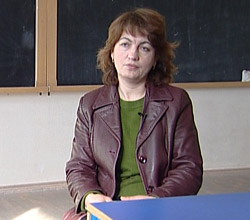

Our interview interrupted Tamar Galstyan's chemistry class at the Aygepar Secondary School. The schoolchildren quietly listened to their teacher's narrative, an account of war in every sense of the word. "We would quickly escape to bunkers during the shooting. There were days that we wouldn't leave the bunkers from morning till night," Galstyan said. She said that these events damaged the quality of education - academic performance suffered-but there was only so much you could ask of schoolchildren.

"What started the conflict?" I asked. She was quiet, perhaps surprised or confused. Then she spoke up, as if she had recalled something. "There was no real animosity between the Azeris and us. I don't know where that enmity came from and how it implanted itself within us."

The schoolteacher did not dismiss the political and historical causes of the conflict, but she could also not comprehend how two neighboring villages, having lived together in peace and harmony for decades, could get caught up in this clash. "What problems could one working man have with another? Ordinary citizens can't do anything about what people in power do or don't do; I don't know anything about any of that. But there was no conflict between the working people of our two villagers," she said and assured us, "If peace is established, we will once again be on good terms with each other."

|

|

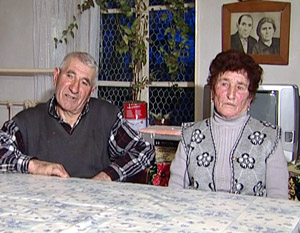

| Tamar Galstyan | Nvard Petrosyan |

Aygepar's only connection to the outside world, or even to the capital, is through the government television channels H1 and H2. No newspapers are sold here, there are no radio stations, and the Internet doesn't even exist in their wildest dreams, because in Aygepar, it takes heroic effort to even use the phone. Although the official television channels may not campaign for war, they do not preach the necessity of peace, either. In Aygepar, people speak of peace in a way that suggests that it is a topic of everyday discussion. Here, they realize that peace is a necessity, but not everyone sees it as a possibility.

Nvard Petrosyan, a geography teacher at the Aygepar School, is plagued with domestic problems. Her ancestral home was ruined during the war. His father lost an arm in the fighting. "I can't forget that the home that took fifty years to build no longer exists," she said.

In Petrosyan's view, her generation will be unable to make peace, because they cannot forget all that they have seen. Tamar Galstyan believes that peace will solve all their problems, but sees a large obstacle in its path, "There have been victims on their side as well as ours. That wound will not heal, or may heal only with time."

The word "victim" here embraces those residents of Aygepar specifically who were killed during military action. Victims of the neighboring village are a slightly more abstract concept. They do not know whether or not their friends or their family members are alive. The situation is similar in the Azeri village; the victims from the Armenian side remain nameless. The two villages, at a distance of only 200 meters from each other, are left with doubt and vague assumptions in the absence of dialogue. The possibility of coming face to face or meeting the future frightens both sides: "What if it turned out that we had killed our friend's child?"

"We went to Kazakh for a wedding. They were very hospitable; we stayed overnight at their house," recalled 80-year old Aygepar resident Aram Atoyan. But he also remembered how a grenade hit the second floor of his house and destroyed his glass-lined balcony. "My daughter-in-law was sitting here with her three-year old child, and we were with them. The child lost his tongue in that incident, it got cut off. We went to Yerevan three times to seek some kind of help for him, but nothing worked."

Aram Atoyan's wife, Paytsar Andreasyan, also remembered the friendship they had with the neighboring Azeris. She spoke of how friendly they were in trade and in other relations as well, but when we mentioned the possibility of peace, she thought for a while and then said, her voice heavy with emotion, "How can we make peace with them when they've killed so many of our young men? Centuries must pass - not just years - centuries."

Aram Atoyan's wife, Paytsar Andreasyan, also remembered the friendship they had with the neighboring Azeris. She spoke of how friendly they were in trade and in other relations as well, but when we mentioned the possibility of peace, she thought for a while and then said, her voice heavy with emotion, "How can we make peace with them when they've killed so many of our young men? Centuries must pass - not just years - centuries."

Aram Atoyan does not share his wife's pessimism. He thinks that once peace is established, people will come and go as they did in the past, and friendship will develop, but he is not sure if they will live to see that day. "We may not be going over there now, but perhaps the next generation will come and go, and they will be friends," he said.

Peace in Aygepar has not taken shape yet. Nobody knows what it will look like. Everyone, old and young, realizes that it will be nothing like the relationship they had during Soviet times, which they often describe using an Azeri word, dostutyun , or friendship. That is why when you ask about peace they say, "I don't know about peace, but war has destroyed houses and killed children."

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment