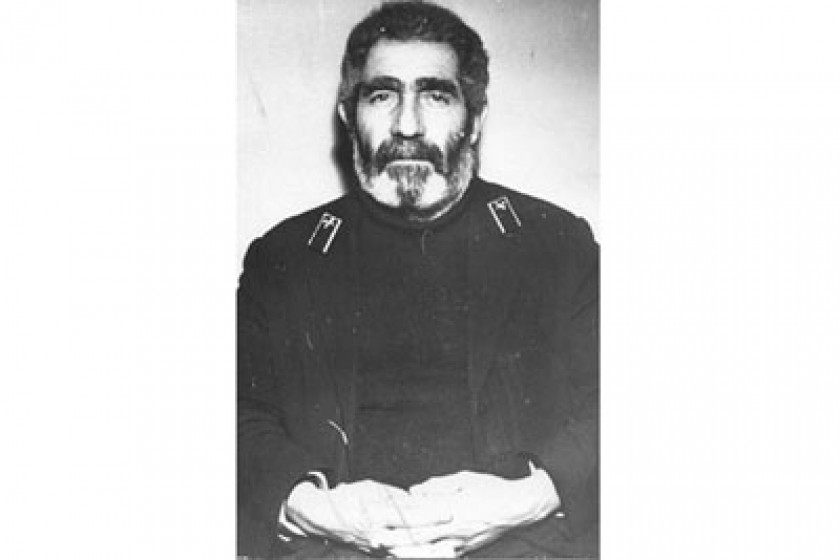

Grandfather Vardan's Tsapatagh

Grandfather Vardan was born in the village of Bartzruni near Vayk. In 1937 his father Hambartzum Khachatryan was labeled an "enemy of the people" and executed by a firing squad at the Yerevan prison. In 1942, sixteen-year-old Vardan joined the army. Too young for the front, he served six years in the supply division of a brigade near Leninakan (now Gyumri), where he fed the brigade the potatoes he grew himself. Afterwards he came to Yerevan, married, built two homes and spent fifty years working for the Yerevan Railway. His wife died in 2000; he and his second wife started a new life in Tsapatagh, a border village in the Gegharkunik Marz. Moving into a house that had been abandoned, they planted fruit-trees, and potatoes and beans.

The impulse to create within a man like that does not cease even after eighty years. Vardan wonders when he hears that someone doesn't have a job, or lives poorly, or has nothing to eat. At those moments he doesn't say anything, he just looks at his own hands and turns them over. He has never asked anyone for anything. After fifty years of work the government gives him 11, 000 drams a month - more like alms than a pension. The railway no longer remembers him, and his two children live a hard life in Yerevan. He isn't angry at anyone though. Old as he is, he lives off the land. He bakes his own bread, and feeds the chickens. What he hears on TV surprises him; he wonders why people complain about hard times. He has never complained. His only complaint is with God, who three months ago left him without his beloved wife and friend. He is alone now, but continues to nurture the soil and two cats and a dog, and to plant potatoes and beans.

When the villagers, fearing bird flu, killed all their chickens, Vardan grumbled, "Bird flu? They said that before but I didn't kill a single bird." And he kept his chickens. Now the whole village comes to him for eggs. He never heard the minister of agriculture, David Lokyan, say that the prime minister said there was no bird flu in Armenia, or the journalists say the opposite. The villagers listened to the journalists, and now they don't have any chickens. Vardan doesn't need to listen to anyone; with his experience and wisdom, he is the one to listen to.

One night, he heard a loud explosion in the yard. "Could it be that it was a bomb from the mountains nearby?" he thought, and went back to sleep with one eye open. In the morning he saw that the firewood shed had collapsed. The mountain slope is covered in black soil, without a gram of clay, so rain causes mudslides that destroy everything in their path. Grandfather Vardan laid wooden foundations and, on his own, began to rebuild the walls.

In Tsapatagh, where Grandfather Vardan lives, the differences that exist in our country are more vividly expressed than in other villages. This is the home of the Tufenkyan Hotel and Restaurant. The hotel is frequented by well-known people who never leave its luxury, and laugh as they look at the border mountains only fifty meters from the windows of their hotel rooms. Even Sevan, a stone's throw away, is too mosquito-infested for them. They lazily walk from their jeeps to the hotel and back. They don't know about Grandfather Vardan, or that they spend more money in a day than he spends in a whole year. But Vardan doesn't give a damn about their jeeps; he wouldn't trade one of his cats for a jeep. It's fine with him that the hotel guests don't get out of their jeeps, don't follow the winding roads he has walked, don't feel what he feels. Grandfather Vardan's Tsapatagh is very different from theirs.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment