An Armenian Painter, Commerce and a Shot of Vodka

"I love rocks. I paint rocks. They show me a tree, but its leaves fall," the stout bearded man talks with friends at a table in his well-lit studio, gesturing with one hand and holding a cigarette in the other.

Martin Akoghlyan is neither one of the most nor the least popular painters. He is just an Armenian painter. Armenian rocks and mountains are what he paints.

He paints and spends most of his time in his studio in the Aresh district. Saturdays and Sundays are reserved for the Vernissage.

To get to Martin's studio, after you have taken a ride to Aresh, you have to enter the yard of a two- floor house, and climb a rickety wooden stairway that screeches after years of painters and sculptors going up and down its steps.

The studio of two rooms is an explosion of bright color canvases, brushes, paints, sketches, and cigarette butts.

In the first room, an old wardrobe with winding patterns faces a wall-sized unfinished painting. The walls are covered with old photographs and paintings.

"One should turn a stone or a brook into a symbol. Armenia is full of symbols," Martin talks to his friends in the next room in a loud voice.

The easel in the second room, where Martin usually paints, stands next to one of the windows and reaches to the ceiling. Colorful and lively paintings of mountains and rocks cover the old green walls. Yeghegnadzor, Bjni, Garni, Oshakan are all there. In the darker corner is the table where Martin and other painters, sculptors, and any other people gather in the evenings for a drink under the paintings.

"If you put a rock in front of ten Armenian villagers, seven of them will carve it, however they can," Martin continues at the table, gulping a glass of vodka. "The Armenian man knows the melody of the rock. Each stone has its history. I try to read it and transfer it to the viewer."

He takes his guests, a sculptor, two businessmen and a politician, to the front room of the studio. He pulls out several paintings putting some on the floor and leaning others on the walls and on each other. These are from the period when Martin concentrated on history and legends. There's Hayk Nahapet, the birth of Vahagn, King Artashes and Princess Satenik, Mesrop Mashtots and Sahak Partev.

"I don't know, Vahan jan, how well I paint," he says simply to the politician, pointing at the pictures on the floor. "For me the spiritual is important, the inner energy of Hayk."

Then they go back to the room, to the table covered with cheese sandwiches and bottles of vodka, where sentences become less and less connected, and love for Armenia grows stronger with each glass.

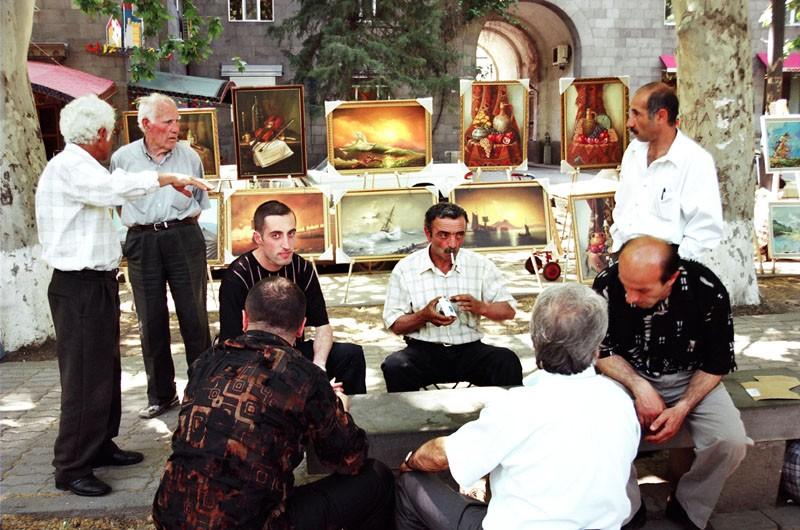

The conversations continue at the Vernisage on Saturdays and Sundays, this time mostly between painters. Martin stands next to his paintings, shifting the weight of his body from one foot to another and peeks at passers by, or sits on a low chair and chats with other painters. A bottle of beer or a cup of coffee at Koziryok are the only escapes, though not too rare.

Martin is a painter concerned with keeping the unique style of his paintings. Others are more afraid of an individual approach and follow what the visitors often buy. This way some paintings in Vernissage are suspiciously similar to each other. Mount Ararat, Biblical themes, sea, nature, pomegranates and Armenian carpets repeat themselves.

"People buy whatever reaches their consciousness," says painter Tigran Avakyan, who sells his paintings in the Vernissage. "One should have a certain amount of intellect to understand good paintings. But the painter should not think whether they will buy his paintings or not. That puts him in limits. If I painted what they bought I would be rich."

"When you sell what you want and not what they usually buy, it is interesting but risky," Martin says.

"One should express his life and his views," says another painter, Sergei Maltsev. "What others do is not art, it is commerce."

As for the development of the commerce of valuable paintings, "The business of art is not developed in Armenia yet," Martin says. "It is not only a problem of painting, but one of national ideology."

The intellectual level and the level of national ideology are not the only reasons for the hardships of the appreciation of paintings.

"If a million come to a concert they can appreciate it right away," Martin says, "Only 5-10 people visit a painting exhibition. The millionth person comes five years later. Time is necessary to perceive the art of the painter. That's the difficulty of our job."

The painters also sell their works privately. Many have gone and come back, or are now abroad selling their paintings to private buyers or galleries. Martin also spent two years in Greece during the difficult early 1990s earning money for his family.

"I had private orders or sold works to a gallery," he says, "which then sold them for a higher price."

But going abroad is not necessarily more profitable than selling to individual customers or standing in the Vernissage. Most of the painters try all ways.

Months may pass before they sell a single painting. As for the prices, "the cheapest is the gift," Martin says, "and the most expensive is an amount enough to pay my debts and spend the rest to drink with friends."

"But usually it happens the other way around," a friend tells him. "You first drink it with all the friends, and then there's nothing left for paying back debts," and they laugh.

Martin empties another glass of vodka and says, "I love what I do, I enjoy doing it. I paint for myself and for my land."

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment