Community Monitoring of Armenia’s Wildlife: Arpa Project Offers New Approach

The bus takes us to a point near the abandoned village of Amaghu, in Armenia’s Vayots Dzor Province.

We get off the bus, greet the forest rangers dressed from head to foot in sandy camouflage uniforms and board a Russian UAZ Patriot SUV.

For the next ten minutes we drive off road to a vista point 1600 to 1800 meters above sea level.

“Here they are, look!” shouts our ranger, pointing to a herd of Armenian mouflons as they zip down past our car. We are all excited to see them, especially the cute baby goats. “I guess we’ll see more of them,” the ranger says.

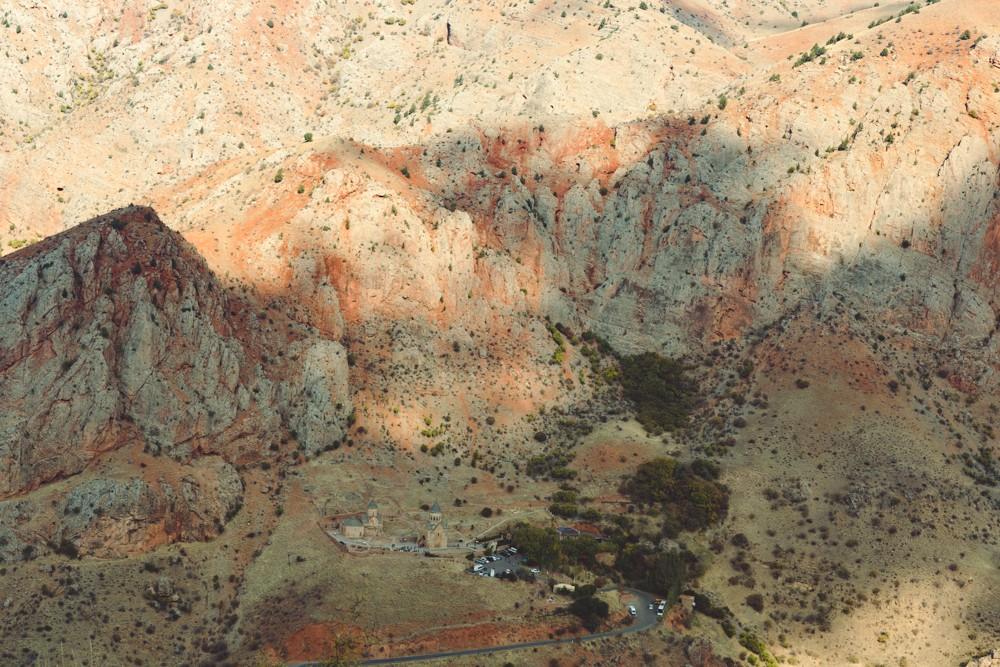

We finally reach the vista point from where a mind-blowing view opens up – the arid rocky Gnishik Gorge with rocks of all shades of red, yellow and grey. It’s probably the most colorful part of the Zangezur Ridge, with dark green bushy junipers growing here and there. You can see the 13th century Noravank Monastery and the Amaghu River down below.

Vayots Dzor has always impressed me with its steep mountains. Here, I feel like I’m in a sci-fi movie - everything seems alien. For a moment my mind disconnects from the reality of standing at the edge of the cliff and I must remind myself that this place is real and has a name.

The area called the Arpa Protected Landscape is Armenia’s first community-managed protected area.

Established in 2014, the area is managed by the Arpa Environmental Foundation (AEF), representing the nearby villages of Khachik, Gnishik and Areni.

I read in the brochure I had taken earlier from the visitor center that “the main goal for creation of the Arpa Protected Landscape is protection of the open juniper forest, phryganoid vegetation and semi-desert ecosystems, human-altered and natural landscapes, rare and threatened species of flora and fauna.”

The area comprises some 3,000 hectares containing around 800 plant species, 47 of which are registered in the Red Book of Armenia.

39 mammal species, of which 14 are nationally or globally threatened, inhabit the area. These include Armenian mouflons, Bezoar goats, Brown bears and famous Persian (Caucasian) leopard named Neo/Leo, who settled here last year and has already become a star of the Armenian internet.

190 species of birds live here, most famous of which are Egyptian and Cinereous vultures.

The AEF’s social media network is full of videos of all the animals living here.

The AEF monitors the area with trap cameras and drones. The four rangers work every day to prevent poaching.

“They know we are monitoring, that we are here, and so they don’t come,” Vardges Karakhanian, one of the four rangers, tells me.

The other three rangers usually avoid giving video interviews and prefer not to be photographed, arguing that it’s important not to be widely recognized by potential poachers.

During Soviet times, some 4,000 Bezoar goats and Armenian mouflons lived in the area.

Even though illegal hunting was not uncommon then, the situation dramatically worsened from the early 1990 until the early 2000s, when poaching became the norm and the animals systematically killed.

Many species were thus endangered species, some to the point of extinction.

Many forested lands in Vayots Dzor were leased to or privatized for various business activities (construction of hydroelectric power stations etc.). Many of the owners include government officials.

Legal gaps, lack of punishment and the absence of institutional nature protection turned this region of Armenia into a favorite hunting haunt for common folk and local oligarchs.

One of the rangers I spoke to said that even though a famous tycoon and his affiliates rented and purchased some animal habituated lands, they hunt less than before.

Currently, around 400 wild goats live here, up from a low of 100.

“If the leopard comes and stays here, it means it has enough food. This means the whole ecosystem, the food chain, can begin to recover. This is the best sign of success,” says Caucasus Nature Fund Director Arman Vermishian.

The AEF has received funds from the Caucasus Nature Fund (CNF), World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF).

Some €180,000 have been invested in the protection of the area over the past five years. The money covers the salaries of the staff and rangers, funds for building the visitor center with guesthouse, and other activities for developing eco-tourism.

“The approach we have adopted hasn’t spread to other areas, but we are trying to be an example showing that this [way of protecting nature - ed.] works,” says Arus Nersisian, an Areni resident who runs the AEF.

The AEF is trying to become self-sustainable.

Thus, it offers tourists paid hiking tours, off-road jeep tours, bird and wildlife watching, horseback and something they call glamping - “glamorous camping is where stunning nature meets modern luxury”.

The guesthouse is made of old shipping containers which they’ve renovated. It’s right near the visitor center, just a 15-minute drive away from the protected area.

Some tourists prefer to stay in the homes of Gnishik, Khachik or Areni residents. There aren’t many tourists who opt for this, but it’s still a source of income for the locals.

Nersisian says they want to develop a sustainable venture, so they need more people to learn about the place and come see it themselves.

The mild October sun comes and goes, changing the palette of the rocks with each passing ray.

We spend three hours in the area. Ranger Samvel spots another herd of goats high above us on the steep ledge. We take turns watching them through binoculars.

“Had we come here early in the morning, we’d see many more of them,” he tells me, adding that it’s much harder to spot Neo the leopard since he’s very cautious and usually sleeps in the caves during the day and hunts during the night.

I gather and eat some wild cornelian cherries. It is time to return to Yerevan.

We drive back to Amaghu to catch the bus. I leave with plans to come back again for hiking next spring.

Follow Samson on Twitter - @mrtrsyns

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment