Squandering Armenia’s “Blue Jewel”: Fingerlings Destined to Bolster Endangered Sevan Native Species Used to Make Omelets

Summer algae blooms have become commonplace in Lake Sevan, Armenia’s “blue jewel” nestled in the mountains of the country’s Gegharkunik Province.

To get a scientific take on the problem, Hetq talked to Tigran Vardanyan, a senior researcher at the Institute of Hydroecology and Ichthyology of the National Academy of Sciences of Armenia.

Here, Vardanyan approaches the problem from his field of expertise.

The reasons for the Sevan algae blooms are diverse, most notably the waste runoff into the lake that brings large amounts of organic and inorganic substances, the drop in the water level, and persistent overfishing of fish and crayfish. Most scientists familiar with the issue would not disagree with the above.

Fish and crawfish are natural biomaterial filters

As the biomass accumulates in the lake and creates a favorable environment for the rapid growth of cyanobacteria, fish and crayfish, at the top level the lake's food chain, become the "accumulators" of that biomaterial. That is, when fish, for example, feed on phytoplankton (including cyanobacteria), zooplankton and bottom invertebrates, thus producing high-quality edible proteins in their bodies for humans, it promotes the removal of biomaterials when the animals are harvested. The same goes for the crayfish, which not only feed on detritus, like the Sevan koghak/scraper (a subspecies of Caucasian scraper), but also draws organic compounds from the water to synthesize the chitin (a long-chain polymer of N-acetyl glucosamine) needed for their exoskeletons.

"The more protein we remove from the lake, the more organic portion we remove, can contribute to the reduction of organic matter in Sevan. But harvesting must be balanced, and supervised,” says ichthyologist Vardanyan.

It is clear that in the case of overfishing, the ecological balance is disturbed: biomaterials continue to accumulate in the lake, but due to the low, depleted stocks of fish and crayfish, this organic mass is removed from the lake at a lesser degree.

Asked whether fish and crayfish feed on the same cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) that have caused Lake Sevan to bloom in the 1960s and 1970s and again in the last two years, Vardanyan said that the scraper can eat the algae but not the crayfish, whose mouth structure only allows it to feed on sediments.

Cyanobacteria are both toxic and non-toxic. 2018 studies in Sevan have shown that those that thrive in the lake produce toxic substances, specifically microcystin. In this regard, Armenian scientists are currently conducting research on their own initiative on how toxic substances can affect the body of fish. At the same time, Vardanyan can’t say with any certainty the degree to which the algae blooms are impacting the lake’s fish stocks. He says he has not noticed any link.

There are 8 fish species in Sevan today, 3 of which arenative

One of Sevan’s most ecologically painful issues is the reduction of the lake’s biodiversity due to overfishing, the artificial lowering of the water level and the pollution dumped by rivers flowing into the lake.

Vardanyan says that currently eight fish species are found in Sevan. Those native to the lake are the endangered Sevan trout (Salmo ischchan), the Sevan scraper (Capoeta capoeta sevangi) and the Sevan barbel (Barbus goktschaicus). The others are the common whitefish (Coregonus lavaretus), Prussian carp (Carassius gibelio), wild common carp (Cyprinus carpio), South Caspian sprilin (Alburnoides bipunctatus), topmouth gudgeon (Pseudorasbora parva), and one species of crayfish - Pontastacus leptodactylus.

It was Vardanyan who discovered the presence of South Caspian sprilin and topmouth gudgeon in the lake in 2010 and 2011, respectively. It was the topic of his PhD dissertation.

The Sevan trout used to be the main fish species in Lake Sevan, but because of the lowering of the water level (since the 1930s) and poaching, its stocks have sharply decreased. In 1976, commercial harvesting of the fish was banned in the USSR, and in 1978, when it was included in the USSR Red Book of rare and threatened species, all fishing for the species was banned. The trout is now in Armenia’s Red Book and all fishing is prohibited. There are four subspecies: summer bakhtak, gegharkuni, winter ishkhan and bojak.

The winter ishkhan was the largest subspecies of the trout, and the bojak the smallest. Prior the 1970s, the annual harvest for the winter ishkhan was 200-250 tons, and 100 tons for the bojak. The last reliable winter ishkhan harvest was in 1982 near the northeastern shores of Greater Sevan, and 1986 for the bojak. In contrast to the bojak, for which there were no attempts at artificial propagation, similar attempts made in the 1970s and 1980s for the winter ishkhan were discontinued due to a lack of wild mature fish.

Vardanyan says that winter ishkhan were able to reach 18-20 kg, that is, it was a fish with growth potential, but it took years. Fish growth was inhibited due to overfishing. According to the official website of Sevan National Park, there were even fish aged 15-16, up to one meter long and weighing 16-24 kg.

The summer bakhtak that exist today lay their eggs in April-June (hence the name), mainly in rivers flowing into the lake and partly in the lake. The gegharkuni lays its eggs in rivers in October-January.

Vardanyan says that the biggest trout he saw weighed 9.5 kg and was caught three years ago. According to the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), both the summer trout and gegharkuni are considered in critical condition. Their artificial propagation continues today, which we will discuss below. Outside of Armenia, the trout is found only in Kyrgyzstan's Issyk-Kul Lake, where it was introduced in the 1970s.

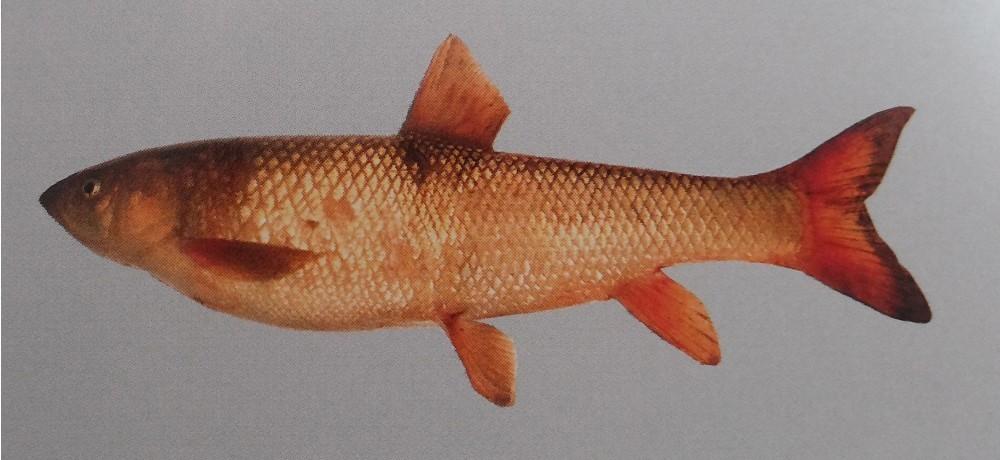

The Sevan scraper, a subspecies of Caucasian scraper, is native to Armenia, and is found across the country, especially in Lake Sevan. According to the Sevan National Park website, by the time the lake level dropped in the 1930s, the fish accounted for 40% of Sevan's total fish catch. The Salmo ischchan accounted for 50%.

By 1965, the scraper share of the harvest dropped to 32%, and the Salmo ischchan to 27.5%.

Commercial scraper harvesting in Sevan once totaled 300-500 tons a year. All fishing for the species was banned in 1995 and it’s included in the Red Book of Armenia. According IUCN Red List, the Sevan scraper is listed as vulnerable. Attempts have been made to introduce it to Georgian and Russian pools.

As mentioned above, theSevan scraper feeds on algae and detritus, as well as onbottom organisms. It is difficult to overestimate the role of this fish in the fight against Lake Sevan algae blooms.

The Sevan barbel is also endemic to Armenia and is found only in Lake Sevan basin. According to the Red Book of Armenia, which includes the species, the fish had commercial value and the annual harvest reached 20-25 tons.

These fish, which spawn in the lake and the rivers flowing into it in June-August, were also affected by the lowering of Sevan’s water level, pollution of the rivers and poaching. Outside the lake, the Sevan barbel only to be found in the middle channel of the Argitchi River. Fishing for the species has been banned since 1981. According to the IUCN Red List, the fish is evaluated as vulnerable.

The number one fish species of Lake Sevan today, by population, is the common whitefish, two subspecies of which were brought to Armenia by the Russian scientist Derzhavin in 1924 from Russia's Chud and Ladoga lakes.

Tigran Vardanyan says the reason for the introduction of the species was that there was a zooplankton in Sevan that was not consumed by native species. Thus, Derzhavin suggested introducing whitefish in to feed on the plankton. By 1965, whitefish occupied first place (40%) among the fish species caught in Sevan, and in the following years it was the main commercial fish species in Sevan. According to the Sevan National Park website, the commercial whitefish biomass reached 12,000-13,000 tons in the 1970s, and the maximum whitefish stocks in Sevan in the late 1980s and early 1990s reached 16,000-18,000 tons.

The species has been greatly impacted by overfishing and poaching.

Vardanyan says that the largest whitefish he’s encountered in Sevan was a 6.3 kg fish he saw last year. He sadly notes that fish weighing as little as 50 grams are now showing up in fishing nets.

As for the other fish species in Sevan, in the 1980s, according to Vardanyan, Prussian carp and wild common carp were introduced to the lake from the pools of the Ararat Valley under unknown circumstances. The crayfish (Pontastacus leptodactilus, now found in Sevan is also an invasive species which, according to the National Park, was first found in the lake in the late 1970s. The crayfish were not found in the rivers flowing into the lake, but it is abundant in the Hrazdan River flowing out of Sevan.

How to deal with illegal poachers?

Among the fish species of Sevan, it is any harvesting of species registered in Armenia’s Red Book is banned - ishkhan, koghak and barbel.

According to Article 292 of the Criminal Code, a fine of 500,000-700,000 AMD or 2-3 months of imprisonment is envisaged in case of illegal extraction of fish or other aquatic animals or commercial aquatic plants, if these actions have caused 1. major damage (200,000 AMD is considered major damage). 2. committed using methods of mass destruction; 3. committed at spawning grounds or migration routes or during spawning. The same acts committed 1. Abuse of official position, 2. by a group of persons with prior consent, are punished with 600,000-1,000,000 AMD or a maximum of 2 years of imprisonment, deprivation of the right to hold certain positions or engage in certain activities for a maximum of 3 years or without it.

Article 295 of the Criminal Code stipulates that the destruction of endangered or rare habitats of organisms registered in the RA Red Book, which intentionally or negligently caused the extinction (death) of entire populations of those organisms, is punishable by a fine of 200,000-600,000 drams or a maximum of 3 years imprisonment.

If illegal fishing does not meet the requirements of the Criminal Code and is therefore not a crime, it falls within the scope of an administrative offense, the penalties of which are set out in the Code of Administrative Offenses. Depending on the nature of the violation, the Code imposes a fine of 50,000 to 250,000 drams with confiscation of weapons, harvesting gear and the harvest, as well as deprivation of the right to harvest for up to three years.

In addition to criminal and administrative liability, the Law on Tariffs for Compensation for Damage Caused to Fauna and Flora as a Result of Environmental Violations stipulates that, in particular, a person is obliged to compensate 50,000 drams for each harvester (regardless of its age) for the summer ishkhan and gegharkuni. 10,000 drams for Sevan koghak, and 25,000 drams for Sevan barbel.

The Armenian government has introduced new harvesting regulations

In November 2019, the Armenian government adopted a decision on the restoration, preservation and reproduction of fish and crayfish stocks in Lake Sevan, as well as a calculation of their reserves, and the commercial harvesting amounts for fish and crayfish. The decision underwent some changes in June this year. In particular, it states that wildlife researchers should study Lake Sevan fish and crayfish stocks to determine the quantities of whitefish, carp and crayfish industrial fisheries, as well as to collect data on ishkhan, koghak, barbel and other species.

In this regard, ichthyologist Tigran Vardanyan notes that the Institute of Hydroecology and Ichthyology last year, with state support, purchased a Norwegian-made sound echo-sounder to accurately assess fish stocks. Vardanyan says that in the past they worked with another device made in Korea, which was old and the accuracy was poor, but the Armenian specialists were able to get the most reliable data with their methodology, which was proved by test measurements of Russian colleagues, the results of which matched the data received by Armenian scientists.

The government's decision also stipulates that the annual programs for Lake Sevan will set the maximum harvesting rates, the terms of contracts with harvesters and fishermen, the size and weight of fish and crayfish allowed for harvesting, the means of entry, and the entry and exit points for boats.

Based on this decision, in June, the government made a change to the 2020 Lake Sevan annual program, which was adopted in September last year. Accordingly, the annual program stipulates that only whitefish, carp and crayfish harvesting is allowed in Sevan this year.

Relentless fishing severely damages propagation efforts

Tigran Vardanyan says that it is necessary to truly ban fishing for the Red Book ishkhan, koghak and barbel for at least four or five years because they’re all now caught under the name of whitefish or carp. He believes a certain stock of endemic species should be allowed to produce in the lake for several years. Only afterwards, when an evaluation has been made, can any thought of commercial fishing be floated.

Vardanyan is not only a scientist, but also head of Sevan Ishkhan CJSC, which raises fish fry. This company and Sevan Aqua CJSC were established by the Foundation for Restoration of Sevan Trout Stocks and Development for Aquaculture in 2014 and 2015 respectively. Prior to this, the state used to buy fish fry to release in Sevan mainly from private fish farms operating in the Ararat Valley. Sevan Ishkhan is in Kartchaghbyur community in Gegharkunik Province.

Sevan Aqua is a fish farming company breeding trout in Lake Sevan in net cages.

"We are carrying out selection work to purify the trout genes so that we have genuine ishkhan, as it used to be," says Vardanyan, who explains that in the past there were some serious mistakes when breeding trout in artificial conditions, for example, a brown trout gene was mixed with it. After taking the caviar, we no longer need the fish, so it’s processed. To avoid inbreeding, it is not desirable for the caviar to be from the same parental base.”

"Now, all kinds of fish are being caught indiscriminately in the lake, even those that we release. Even small fish weighing 3 or 5 grams are being ruthlessly destroyed by the residents of the neighboring communities. Some keep these small fish in their ponds, some say they make delicious omelets with them. With the help of the state, without sparing any effort, without having a weekend off, we produce, increase the stock, and those people destroy," says an indignant Vardanyan, emphasizing that the government has a serious role to play here.

"I can’t accept their argument that it’s impossible to go to Sevan and reach an agreement consensus with the fishermen to solve the problem. If you offer an alternative to a fisherman who’s having problems providing for his family, then there is a solution. Whitefish is one of the most expensive fish in the world. If we have a lot in Armenia, it does not mean that we do whatever we want with the stock. This fish is not only strategically important, but also plays a major role in economic development. The state can benefit greatly from the sale of whitefish in the domestic or foreign markets," he says, adding that the same fishermen could be involved in state-organized harvesting. They’ll have jobs and stop poaching.

To bolster his argument, Vardanyan accompanies us to the section of the village of Noratus on the Sevan-Martuni-Vardenis highway, where the road crosses the Gavaraget bridge (see above). There is an awful stench under the bridge, the unbearable smells of mud, sewage and rotten animal remains are mixed. He shows the bags under the bridge containing small fish. Unable to sell them, unscrupulous fishermen tossed the bags out of sight, under a bridge where the rotting fish became food for worms and bugs.

Vardanyan says that Gavaraget is one of the most polluted rivers following into Sevan. It not only brings community sewage and other wastewater to the lake but has become a de facto dump. The pollution of the rivers is the reason why the small fish produced by Sevan Ishkhan CJSC are released only in the Masrik and Kartchaghbyur (Makenis) rivers, which are relatively cleaner than the others.

The scientist suggests making sediment collection pools on the rivers as an option

Vardanyan says that it is necessary to first make specific calculations and understand how many and what types of organic and inorganic elements enter Lake Sevan through rivers or during floods.

"First of all, we need to inventory the problems related to the material entering the lake. State bodies having that data need to collect, inventory and develop a targeted solution for each problem. We need to know what materials, in what amounts and from where, enter the lake from agriculture, via people, public catering facilities, etc. Based on this data, it is necessary to decide, for example, the expediency of building treatment plants. It is possible to take a test river, for example the Gavaraget, to make sediment collection ponds or pools on it. There are shores in Sevan, where 1 m high containers and nets are accumulated. They enter through rivers. Not only will such objects be caught in the catch ponds, but also macrophytic organisms, which are aquatic plants, will be formed in the presence of a large amounts of organic matter. It's all nitrogen and phosphorus.”

Vardanyan emphasizes that scientists and specialists must be heard before taking any specific action on Lake Sevan.

On July 21, during a green algae bloom in Sevan, Armenia’s Ministry of Environment reported that as a result of professional consultations, the main reasons for the intensive growth of blue-green algae and the decline of water quality in the lake were high lake water temperature and a high degree of phosphorus.

"Due to the unprecedented volumes of cleaning the forested areas around Lake Sevan, which started in 2019, the concentration of phosphorus in the lake has greatly decreased this year. Last year, about 100 hectares of forested area were cleared from the shores,” the Ministry of the Environment announced, adding that at the same time, mapping and inventory of buildings to be dismantled below the 1901.5 meter mark on the shores of the lake began.

According to the ministry, three measures have been selected as urgent: 1. Prevention of sewage flow from Gegharkunik Province to the lake, 2. Recultivation of areas containing mining waste, 3. Cleaning of polluted riverbeds in the Lake Sevan catchment area.

On August 10, the ministry announced that another 270 hectares of lake shore forest are planned to be cleared this year, of which about 50 have already been cleared. The total number of illegal buildings built below 1905 meters is some 3,800, all of which are subject to dismantling and demolition.

"I have no fear that Sevan cannot be restored. The lake has so much potential that I think it can recover. But this does not mean we should not take practical steps. Our main task is to prevent organic matter from entering the lake from communities via the rivers,” says Tigran Vardanyan.

Photos by Vahe Sarukhanyan and from open sources on the Internet

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment