How Did Armenia Support Artsakh Armenians on Paper and in Reality?

During the war, thousands of Artsakhtsis came to Armenia. Some of them left their homes in such a hurry that they did not even manage to take personal documents and basic necessities with them.

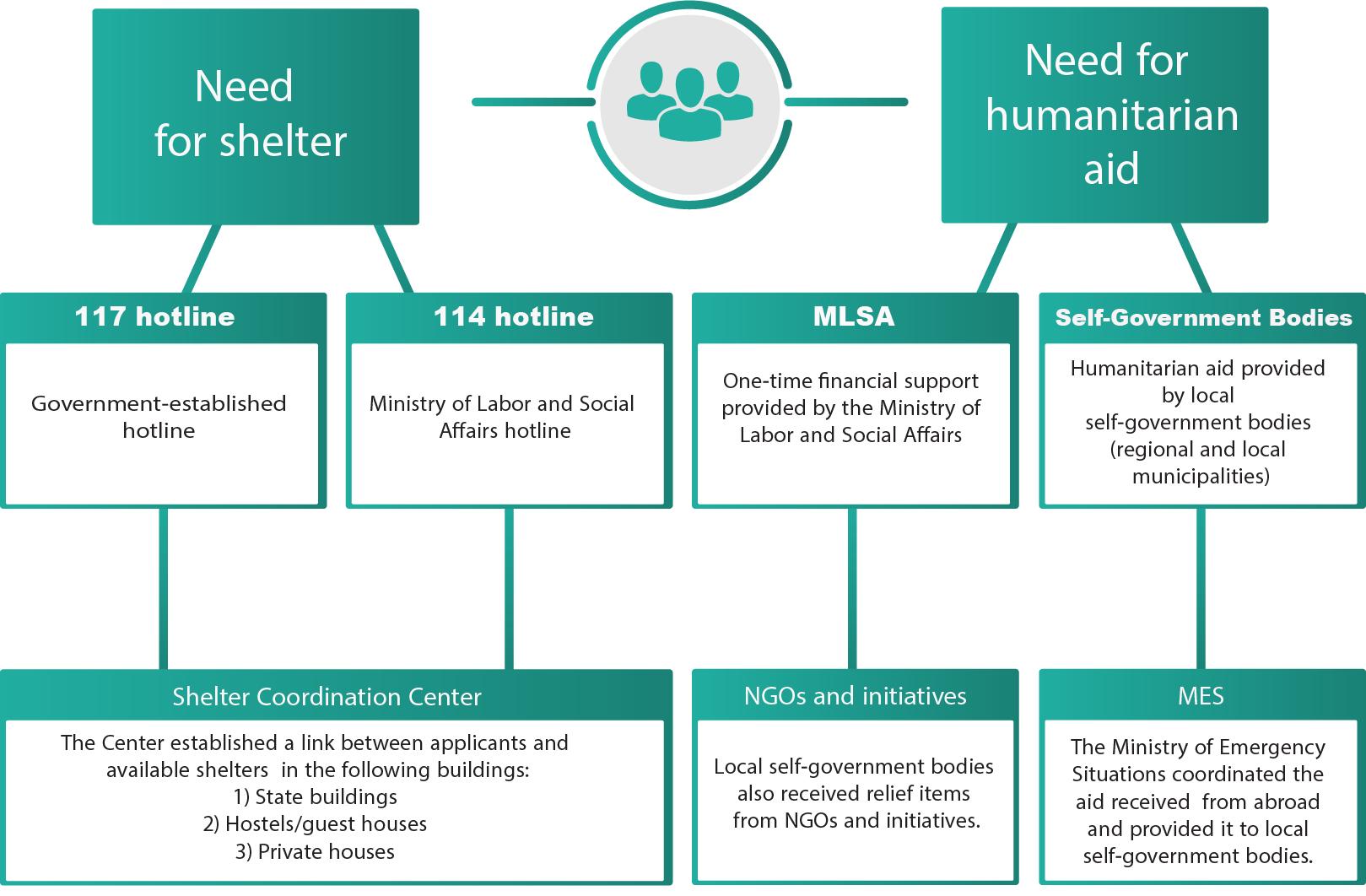

During those days, Armenia’s Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs (MoLSA) was coordinating shelter provision for Artsakhtsis, and later also the distribution of food and hygiene items through the Ministry of Emergency Situations and local self-government bodies.

In parallel, citizens used social media to organize assistance to similarly allocate housing, food, and other necessities.

Gradually, people started complaining about the work carried out by the MoLSA. The Human Rights Defender, in turn, called on the Ministry to “cut out the unaccountable behavior” and realize their own responsibilities, while the Ministry evaluated their work as “high” or “excellent”.

The Hetq Media Factory team examined the work carried out by the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs for several months in an attempt to understand how the Ministry worked during the war and afterwards, how it supported Artsakhtsis, and what mistakes and omissions were made.

“Every day exploding missiles got closer to the village. I remember the rain, the mud. In the evening, we got into the car and came to Goris.” This is how Vladik Poghosyan’s story begins. He is from Kyuratagh village in Hadrut. He is a disabled veteran of the first Artsakh war; one of his hands does not work. He says that they were not able to take anything with them, not even the photograph of his son, Lieutenant Colonel Roman Poghosyan, who was killed during the 2016 April War and who was posthumously awarded with The Battle Cross Order of the first degree.

Only two of Vladik’s five children are still alive: His first child died at six months, and the second one at the age of three. Roman was his third child.

His fourth child is Arman Poghosyan, school principal and mathematics teacher. He was heavily wounded during the recent war in 2020.

Vladik Poghosyan says that he “lived with dignity” in the village with his family of seven, with his daughters-in-law and grandchildren, where he accumulated a sufficient stock of barley, honey, and crops. He refused to leave the village until the last moment. But, when the Azerbaijanis approached the village, they had to leave their home and go to Goris. Later they went to Kanaker to stay with his sister’s son, where 14 people lived in one house.

Realizing that it would be impossible to live like that for long, V. Poghosyan decided to find a house and move his family.

“They called and said that there is a [state supported] shelter in Kanaker. My nephew went and saw it and remarked, ‘Are you serious? Would anyone actually stay here [in such bad conditions]?’ That one didn’t work out. One day they called and said that there is a place just north of the Vahakni district. Anya [my daughter-in-law] and I called for a cab and went there. I saw 50 to 60 people – men, women, and children. Mattresses were laid out on the ground, those really big mattresses provided by the state. There was no door or anything. I said, ‘How am I supposed to live here? How can my wounded son lay on this mattress on the ground.’ I said no, this doesn’t suit us, thank you, we’re leaving,” relays Poghosyan, still trying to find accommodation for his large family.

He says that different individuals were offering houses in Lori and Gyumri. However, his son Arman was wounded and was at a hospital in Yerevan, where they needed to take care of him. That’s why they wanted to live in Yerevan, but they weren’t able to find a suitable shelter.

“I said that I won’t leave my son’s side. I’ll sleep outside, but I won’t leave. I didn’t leave. One day we got news that an emergency shelter had been set up, a shelter for Artsakhtsis. I went there. There was a girl who said that so far there’s nothing. She took my number and gave me her number. He said she would call if there was anything. We’re still calling each other,” relays Vladik. He recalled that later a French Armenian found out about him and offered his house in Abovyan city [roughly 17 km from Yerevan].

To this day Vladik Poghosyan’s family is living in that house. The family’s biggest fear is uncertainty; they don’t know what awaits them. He has no work, and his son is seriously injured and has lost his ability to work. They are entirely dependent on benefactors or state support.

“The field is quite big and there are a lot of missed calls”: The first phase of hotline support

As of December 8, 2020, 5.6 billion Armenian drams have been allocated to the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs from Armenia’s state budget within the framework of a program aimed at providing support to Artsakhtsis.

The first phase began with calling the hotline (117 for the government hotline, 114 for the MoLSA hotline) to arrive in Armenia and receive housing. (Later, Artsakhtsis could apply to stay at a temporary shelter in Yerevan, at 14/1 Nersisyan, for 24 hours until housing was found for them.)

The hotline was used to register Artsakhtsis and provide them with housing so that later on they would receive food, hygiene items, and other necessary support.

Later, the Artsakh government launched an emergency operator service with the hotline number 81-38, which mainly dealt with and continues to deal with providing social and administrative services and various other support services for residents of Artsakh who temporarily relocated to Armenia because of the war.

Firstly, we tried to figure out how the first phase was carried out and how the hotline operated during the war by talking to Hasmik Sarajyan, who heads the MoLSA 114 hotline.

The MoSLA hotline was established in 2013 and, according to the Ministry, it operated 24/7 during the war. Before the state of emergency was declared on March 16th, 2020, the hotline received 10-50 calls per day, but when martial law was declared [September 27, 2020] the number of calls increased significantly, reaching 2,500-3,000 calls per day. According to Hasmik Sarajyan, the hotline employees have mostly been able to answer these calls, but there were missed calls as well.

“Throughout the period of martial law, the hotline has been quite busy. At the same time, there were many difficulties, such as the lack of employees and the emergence of various problems all at once, at a time when those who could solve the problems had to be quickly identified and directed to the citizens,” recalls H. Sarajyan.

At the start, the 114 hotline had 8 operators, but during martial law they were joined by employees from the Ministry’s different subdivisions and volunteers, making the total 35 people. Immediately after the decision was made to include volunteers, a one-day training was organized to inform them about the field they would be operating in and how to answer calls.

However, including volunteers, in turn, created certain difficulties, as additional training was required to introduce them to the work that needed to be carried out. Until then, an initial base of volunteers had not been set up at the Ministry.

“There has always been a need for more employees, regardless of whether there was a state of emergency or not, as the field of social issues is rather big and there are a lot of missed calls; we call as many people back as possible but, unfortunately, that’s not enough,” says H. Sarajanyan. “During martial law, guidelines about the war situation were developed so that employees could readily get involved in the work.”

The MoLSA 114 hotline has been available for solving various social problems, but it has mostly dealt with the issue of shelter.

Aside from questions regarding the provision of shelter, Artsakhtsis have called the hotline to ask about issues related to pensions, benefits, support measures, and humanitarian aid, as well as issues related to soldiers.

Hasmik Sarajanyan notes that many calls have been received regarding humanitarian aid. When contacted through the hotline, employees passed these calls to the relevant bodies, since aid was being organized by local self-government bodies.

“There have been problems with shelter. For example, citizens did not want to go to a certain shelter for objective and subjective reasons. I highly evaluate the work we did to avoid problems with these citizens and make sure that they receive shelter in an appropriate manner. If they complained about a given shelter, this is arbitrary, since it’s possible that they wanted accommodation in Yerevan but were given one in a nearby region,” says the hotline manager, though she does not deny that there were citizens who did not receive assistance.

“In some cases, people didn’t answer the phone numbers they had provided, or maybe it was not their number and they were not able to be contacted. The citizen would call us again or contact us some other way. This mainly concerned shelter. In order to receive food, they had to register with the local self-government bodies and then receive assistance. The main obstacles were organizational; there were 1 or 2 days when it was necessary to get food to citizens within the same day.”

Hasmik Sarajyan also notes that their employees solved Artsakhtsis’ issues as much as was under their jurisdiction and that other cases were redirected to the relevant government entities.

She thinks that, in the future, the hotline has to be developed for all situations to be quickly addressed, so that even “non-working hours become 24-hour operational”.

In the meantime, we were assured by the MoLSA that, thanks to the technical modernization of the hotline, it had been possible to switch to a 24/7 operation mode very quickly.

“We cannot guarantee that we have registered everyone”: Shelter and food

According to the Migration Service (MS) of the Ministry of Territorial Administration and Infrastructure’s most recent data from December 18th, to this day 90,000 people have been relocated from Artsakh to Armenia. With regards to the number of people who returned to Artsakh, the Migration Service does not have information, as indicators are not yet clear.

Nelly Davtyan, the MS Public Relations Officer, told us in an interview [on January 25th] that the data will be available soon.

“We cannot guarantee that we have registered everyone. We have done everything we could to the best of our abilities; people who did not want to be registered were not registered. The numbers of Artsakhtsis who have returned and who are currently in Armenia are currently being filtered. We will have a number in the coming twenty days,” N. Davtyan said.

The MoLSA informed us that Artsakhtsis have been temporarily placed in more than 30 state shelters in different regions of Armenia. At the end of December, more than 1,000 people were living in those shelters. “Please be informed that, as of now [December 28, 2020], more than 1,000 Artsakhtsis are living in temporary shelters in different regions of Armenia [not including hotels or guest houses].”

Shelter allocation was organized by the MoLSA’s Shelter Coordination Center. It was established on October 2nd, 2020 and consists of a team of employees and volunteers from the Ministry and its subordinate institutions. The data of citizens in need of accomodation has mostly been collected through applications to the 117 and 114 hotlines, regional and community municipalities, the Human Rights Defender’s staff, and through other channels. Around 250 applications for shelter were received daily through the hotlines.

State and community buildings, and later also hotels and guest houses, were included in the shelter fund. The process of accommodating Artsakhtsis was carried out by the MoLSA’s Shelter Coordination Center.

After receiving applications via the hotline, employees contacted this center, whose main function was to connect people in need of shelter with those offering it.

David Dadalyan, the coordinator of the Center, recalls that in the beginning random groups were coming to Armenia from Artsakh, as an evacuation process had not yet been initiated. While the flow of people increased, the Center was created at the MoLSA, which involved employees from the Ministry and employees and volunteers from non-profit government subsidiaries.

According to Davit Dadalyan, initially there was a shortage of shelters, but that gap was later filled with the help of private companies and individuals, who called and offered their shelters. Data from December 28th, 2020 show that more than 50 NGOs and 40 charitable and civic initiatives supported the MoLSA during that period.

“They have significantly eased the burden carried by the state. Artsakhtsis were very well received and accommodated in hotels and guest houses. There have been very few complaints. We had private companies support us by providing food and arranging transportation, for example, from Yerevan to the regions,” Dadalyan says.

Speaking about the condition of the shelters, Dadalyan says that, since the initial flow of Artsakhtsis was big and their accommodation was arranged as quickly as possible so that “people could at least have a roof over them”, it’s possible that the condition of the shelters was not prioritized at the time, though complaints have been resolved.

“The main complaints were related to common areas, such as the use of shared bathrooms or families having to share a room with another family. But those problems were temporary, the issues were solved as quickly as possible, and I can assure you that the Ministry went after every call made to the hotline to find solutions. For instance, there have been cases when shared bathrooms and shared conditions were not suitable for people with disabilities. We addressed these problems and, if possible, moved them to shelters with more appropriate accommodations,” says D. Dadalyan.

According to him, in addition to providing shelter, their center also had a team of social workers who assessed the needs of vulnerable families and provided appropriate assistance.

Regarding financial issues, the Center “did not have any expenses or make purchases”, and did not allocate any money for renting or buying shelters or for other purchases; they based their entire work on mobilizing existing means.

Taking everything together, David Dadalyan rates the work of the Shelter Coordination Center as excellent. “There have been difficulties, emotional moments, but I can say that all of them did their jobs honorably and I am very thankful for that.”

According to him, during this period they assisted around 15,000 people, 1,000 of whom presently live in shelters [as of January 20th].

The MoLSA informed us that during the war they provided the Shelter Coordination Center with data concerning the needs of Artsakhtsis (heaters, utensils, technical equipment, baby food, clothing, etc) as well as necessary items for people with disabilities. They also conducted “daily needs assessments” at regional warehouses.

According to the MoLSA, information received via the hotline regarding food, clothing, and hygiene items has also been used to make proper referrals, and that information has been passed on to regional centers; local self-government bodies have distributed the food, clothing, and hygiene items.

The Ministry of Territorial Administration and Infrastructure (MTAI) informed us that food and hygiene packages were provided mainly every 7-14 days and on a monthly basis depending on their size and contents. For the most part, the food packages included flour, potatoes, pasta, rice, oil, buckwheat, and some canned food.

As of January 29, 2021, the MTAI has spent 830 million drams from the state budget to purchase food packages.

“We were not able to contact the hotline for 11 days straight”: Artsakhtsis’ opinion

The Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs says that all applications to support Artsakhtsis have been attended to as quickly as possible. Though there have been complaints while providing assistance, according to Zaruhi Manucharyan, “they have been properly studied and appropriate solutions found.”

In a conversation with us, Artsakhtsis said that there were cases when they did not receive an answer for a week or more after filling out the shelter application and cases where conditions for overnight stays in the shelters were inadequate (i.e. no mattresses, blankets, etc).

According to Z. Manucharyan, these cases do not represent the majority.

“Calls regarding food and other needs of citizens were transferred to the communities and Yerevan’s administrative regions. All buildings occupied by organizations operating under state subordination that were suitable for accommodation, as well as hotels and companies providing accommodation services, were mapped so that the required number of shelters could be provided,” she said.

We talked to ten people who moved to Armenia from Artsakh to try to understand what kind of experience they had with the MoLSA and the hotline. They mentioned that they were told in Artsakh to contact the hotline in case of any questions, but most of those questioned unanimously agreed that their problems were solved very late. Some reported not being able to get through to the hotline at all or being able to connect to the hotline but not receiving appropriate assistance.

They all said that they organized their own evacuation.

Yerazik Avanesyan, a resident of Hadrut, was the head of the Department of Culture and Youth Affairs of the Hadrut regional administration prior to the war, but now she lives in a rented apartment in Yerevan. She says that she contacted the hotline about different issues but wasn’t provided with any solutions. “Food and hygiene items issues were solved after contacting the district municipality. I was connected to the hotline, but it was in vain. I had higher expectations of the hotline on various issues related to registering assistance online. The problems were not solved.”

Ani Tadevosyan (her name has been changed upon her request), who moved from Shushi and now lives in Yerevan, tells us that she was urged by her parents to leave and forced out of Artsakh in the evening, changing two cars on the way. She currently lives in Gyumri.

“We registered ourselves at the regional administration and received support three times in the form of dry food packages and hygiene items,” says Ani. “We contacted them about medical issues, but it was in vain. It wasn’t the timing that mattered. We didn’t receive any useful answers but, thank God, we contacted Artmed Hospital in Yerevan on our own and they served us very well. My problems were not solved with state support; I solved my own problems with the help of individuals, friends, and acquaintances.”

Another resident from Artsakh, Karina Petrosova, tells us that she did not even manage to connect to the hotline. “After moving to Armenia [on October 7th], we took care of our needs on our own. No one greeted us or gave us any direction. I called the 114 hotline day and night for 11 days – my family members too – but we were not able to reach them, not even once. Since we weren’t able to reach the Ministry, we contacted the regional administration in Yerevan, and the next day we were given 2 pillows and 1 blanket. But our problems weren’t solved,” she says.

“The cooperation with the Ministry didn’t work out”: Mistakes and shortcomings registered by the Human Rights Defender

From the first days of the war, the Human Rights Defender’s staff also initiated a process to assist displaced people, organizing their work in two main directions: assisting state entities in carrying out their duties and overseeing the proper implementation of those duties by studying people’s complaints and arranging discussions and monitoring.

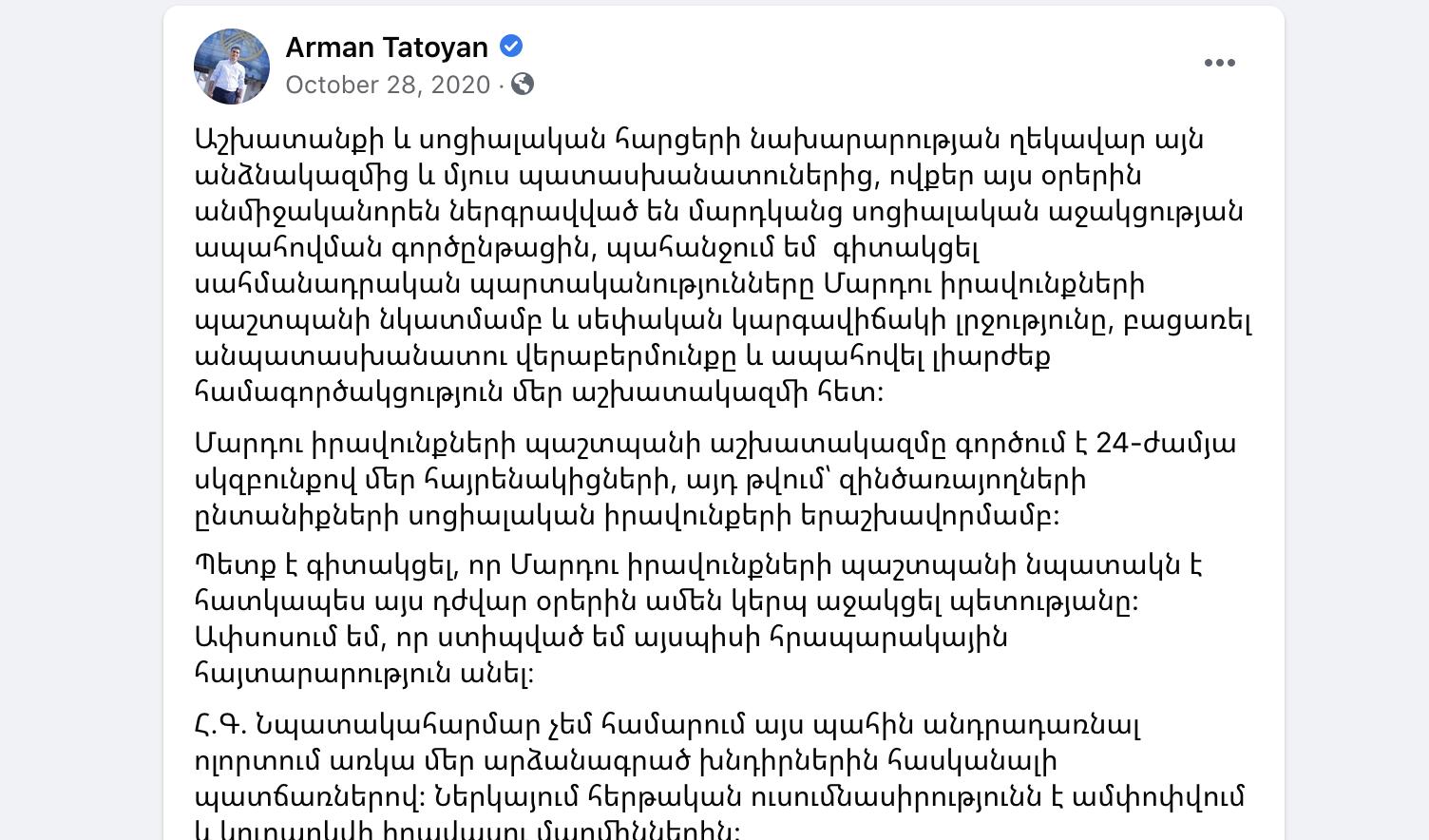

On October 28th, Human Rights Defender Arman Tatoyan published a post on his Facebook page, urging the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs “to cut out the unaccountable behavior”.

“I demand the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs management and other responsible officials who are directly involved in the process of providing social assistance to people at this time to realize their constitutional responsibilities towards the Human Rights Defender and the seriousness of their own position, cut out the unaccountable behavior, and fully cooperate with our staff.”

We asked Tatevik Tokhoyan, Head of the Socio-Economic and Cultural Rights Protection Department of the Human Rights Defender’s Office, to clarify the meaning of the Human Rights Defender’s announcement.

- Tokhoyan noted that, from the very first days of the war, an office for social and material assistance was created, meetings were held with the MoLSA, cooperation mechanisms were developed, and issues known to them at the time were raised. However, their cooperation with the MoLSA did not work out, because officials did not respond, and they often had to submit complaints through the hotline, which, according to Tokhoyan, is unacceptable for state structures.

“We raised the issue that social assistance mechanisms should be invested in, there should be proper assessment of comprehensive needs, assistance criteria should be defined, and there should be proper awareness raising, as the absence of this will lead to human rights violations. We came to various agreements, but we had problems cooperating.; various officials at the Ministry didn’t respond properly, and we were even obliged to intervene,” T. Tokhoyan notes.

Due to the poor cooperation, the Human Rights Defender had to reach out and solve problems with help from individuals, volunteers, and private companies.

“Through monitoring visits, we found out that many people from Artsakh settled in the regions, and the state is not aware of that. When the issue was raised, their justification was that they don’t know where those people are and what problems they have. Later, of course, the temporary housing center was created,” says T. Tokhoyan, adding that they have registered problems there as well. He spoke in particular about the involvement of volunteers in providing assistance. According to Tokhyan, volunteers did not even know their responsibilities and, therefore, could not provide appropriate assistance. “The great desire of volunteers to help was very much welcomed, but they should have at least been trained to work with displaced people and assess their needs, in the same way that they should have been aware of their rights and responsibilities. We witnessed that and notified the Ministry about those issues.”

In addition, despite the fact that the Migration Service and Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs maintained a database at the temporary housing center and had a separate register for individual needs, there was no full identification and assessment of needs: There were no criteria for assessing people’s needs, nor were there criteria for shelter conditions and how these should be chosen.

Tatevik Tokhyan emphasized that shelter was provided without any criteria, without taking into account whether there was a wounded soldier or a pregnant woman in the family.

“There were families that had to split up because there wasn’t enough space in the shelter. Regarding shelters, let me say that the Ministry didn’t know the condition of those shelters beforehand, just that there was this shelter, not this one. But, in the end, that doesn’t suffice. For example, someone goes from Yerevan to Vanadzor and, upon arrival, doesn’t want to stay in those conditions, and they’re forced to arrange more travel, which is an additional waste of resources. We asked the Ministry whether living conditions were assessed after someone settled into a shelter. No assessment was done,” says Tokhyan.

Later, there were the added issues of heating the shelters and the lack of hot water.

“We encountered that problem; there were families, for example in the Ararat region, that couldn’t bathe for several days,” Tatevik Tokhyan notes.

According to the Human Rights Defender’s staff, the state was not able to oversee citizens’ internal movements. And when the local self government bodies joined the assistance work, such as the process of providing food, the absence of standards resulted in people not receiving enough food or hygiene items.

“Problems arose in the food provision process when the local authorities were delaying providing food to families as they waited for the social support center to make a needs assessment so they could distribute food, which was a waste of time,” says Tokhyan.

There were also mistakes when pensions were paid in October; there were inaccuracies in the lists and no awareness-raising campaigns were organized. During the ombudsman’s visits, it turned out that even community leaders were not aware of their duties.

“Starting the data collection late was also a problem. They didn’t know the number of people or where a person or a family was located – half of a family was in one region, the other half in another region,” T. Takhoyan says.

According to the ombudsman’s office, psychological support was also initiated late, “Initially, the Ministry of Emergency situations organized psychological support, and later the hotline service was added. However, the process was not carried out systematically and continually, nor through the same psychologist who was already familiar with the person,” says T. Tokhyan.

As different state structures “were unaware of their functions” due to an incorrect division of labor, there were obstacles for the Human Rights Defender to collaborate when dealing with them as well.

Feedback: What do social networks say about the work of the state?

Citizens confirm the issues raised by the Human Rights Defender. In the very first days of the war, the private sector self-organized very quickly; support groups for Artsakhtsis were created on social networks, where people were trying to provide Artsakhtsis with assistance, from food to shelters.

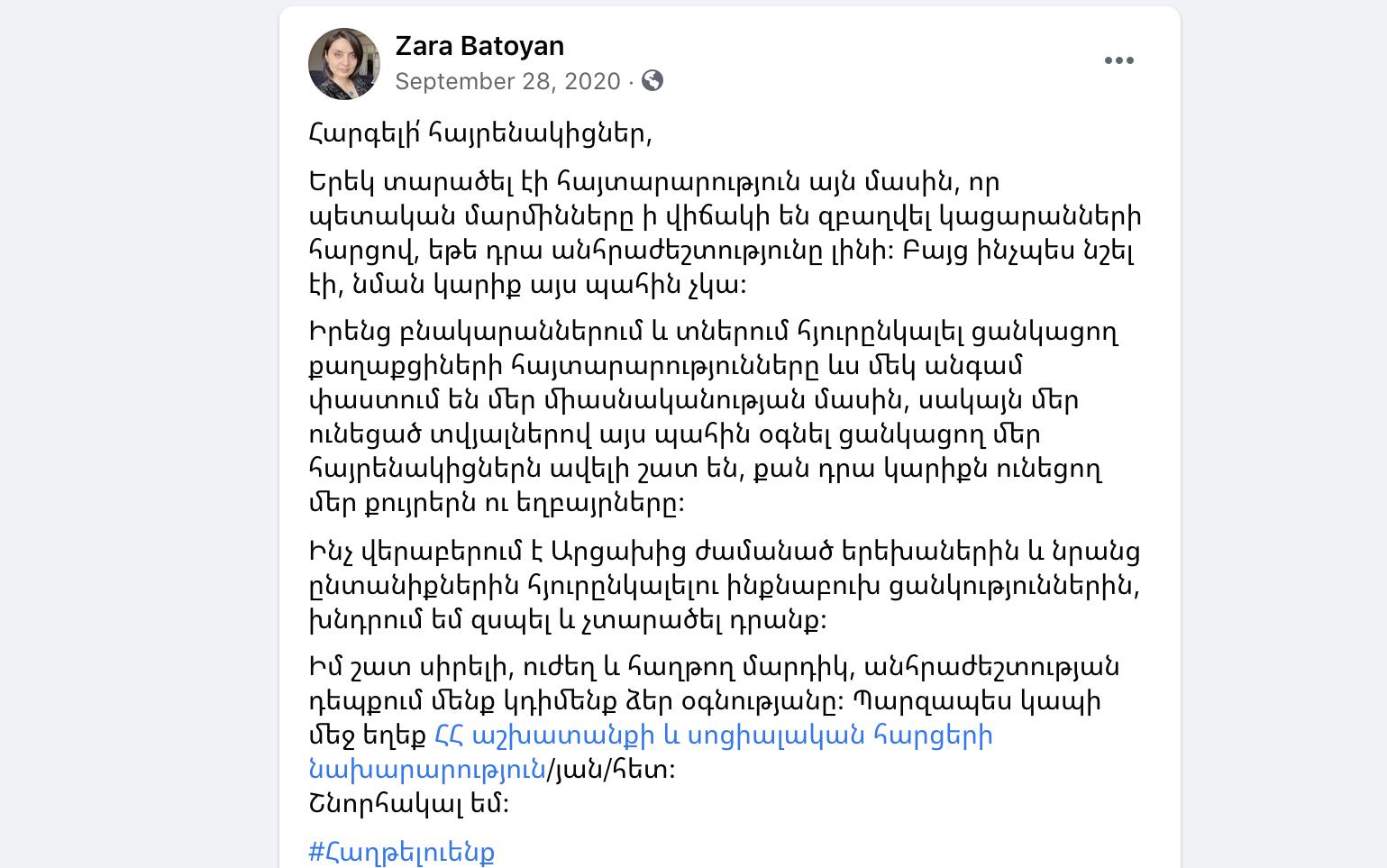

However, this was immediately followed by an announcement from former MoLSA Minister Zaruhi Batoyan, who on September 28th said that it was not necessary to gather aid for people displaced from Artsakh or to look for housing on public platforms, as the Ministry would handle everything.

[Translation]

Zaruhi Batoyan Screenshot

Dear compatriots,

Yesterday I made an announcement that state entities will be able to handle the issue of shelter should the need arise. But, as I noted, there is no such need at the moment.

The announcements made by citizens who want to host people in their apartments and houses prove our unity once more; however, according to information that we have at the present moment, there are more people who want to help than sisters and brothers who need help.

As for those who want to take it upon themselves to host children and their families arriving from Artsakh, please hold back and do not pass on those messages.

My beloved, strong, and victorious people, we will reach out to you if necessary. Just be in touch with the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs. Thank you.

#wewillwin

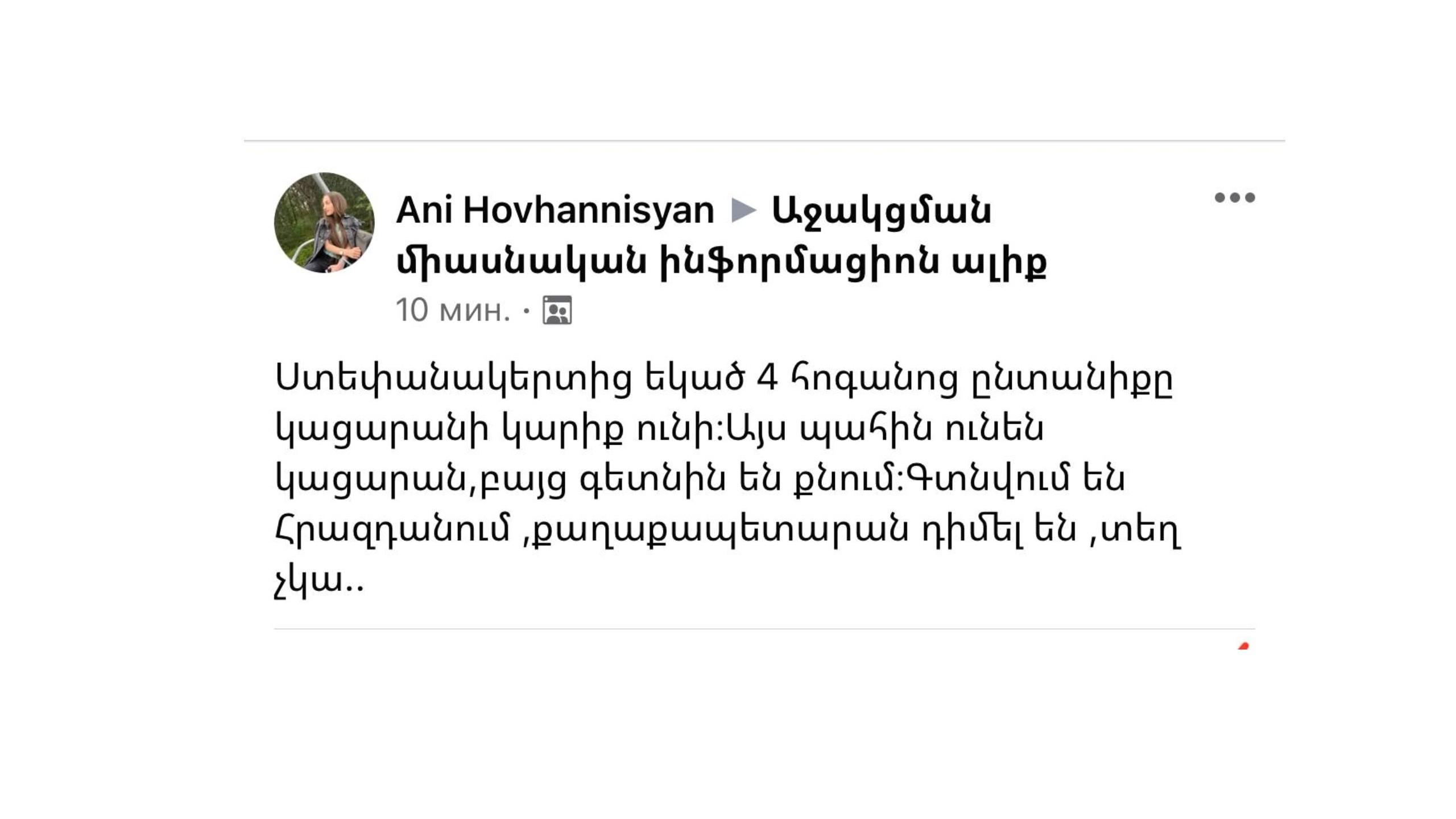

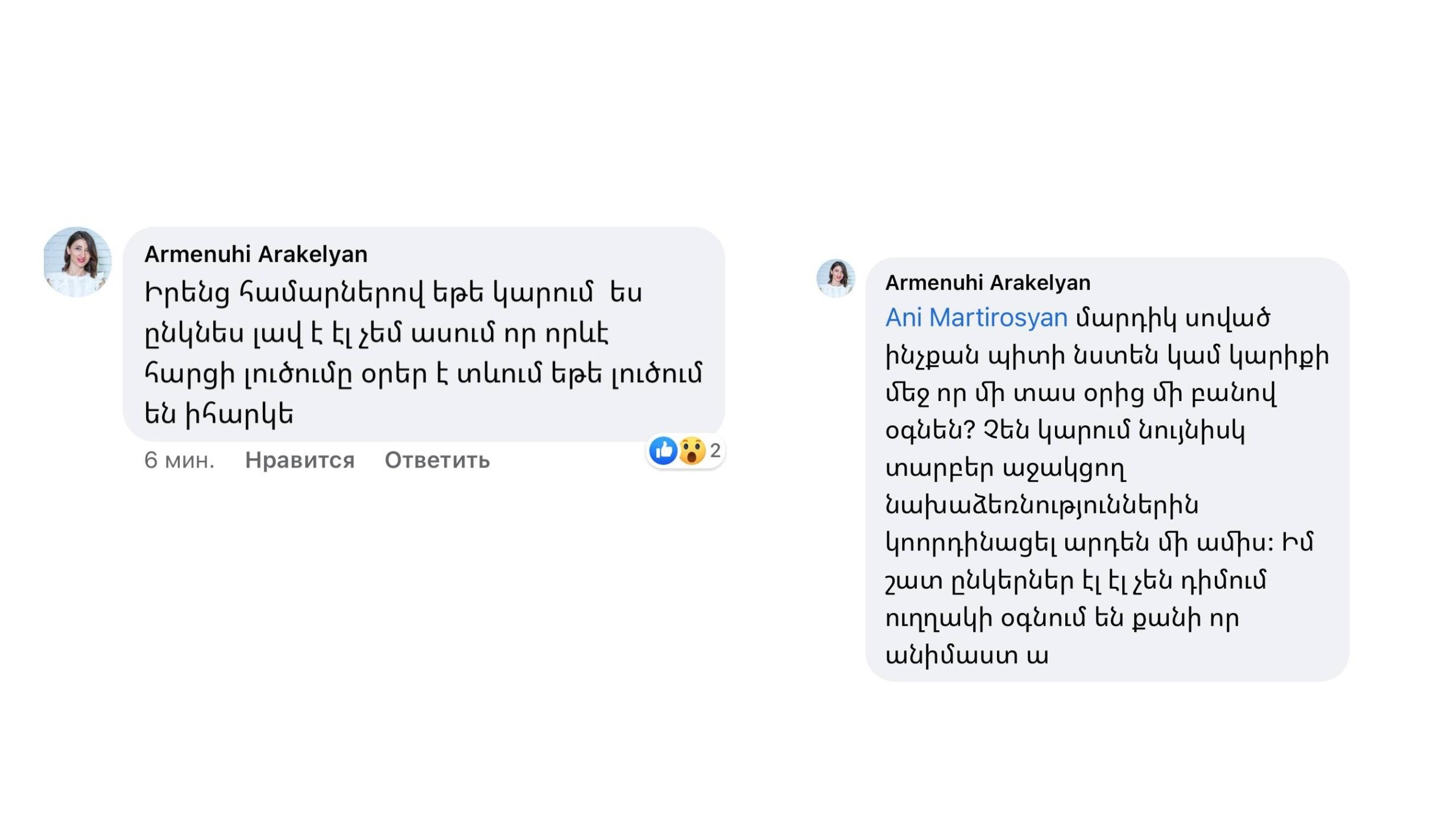

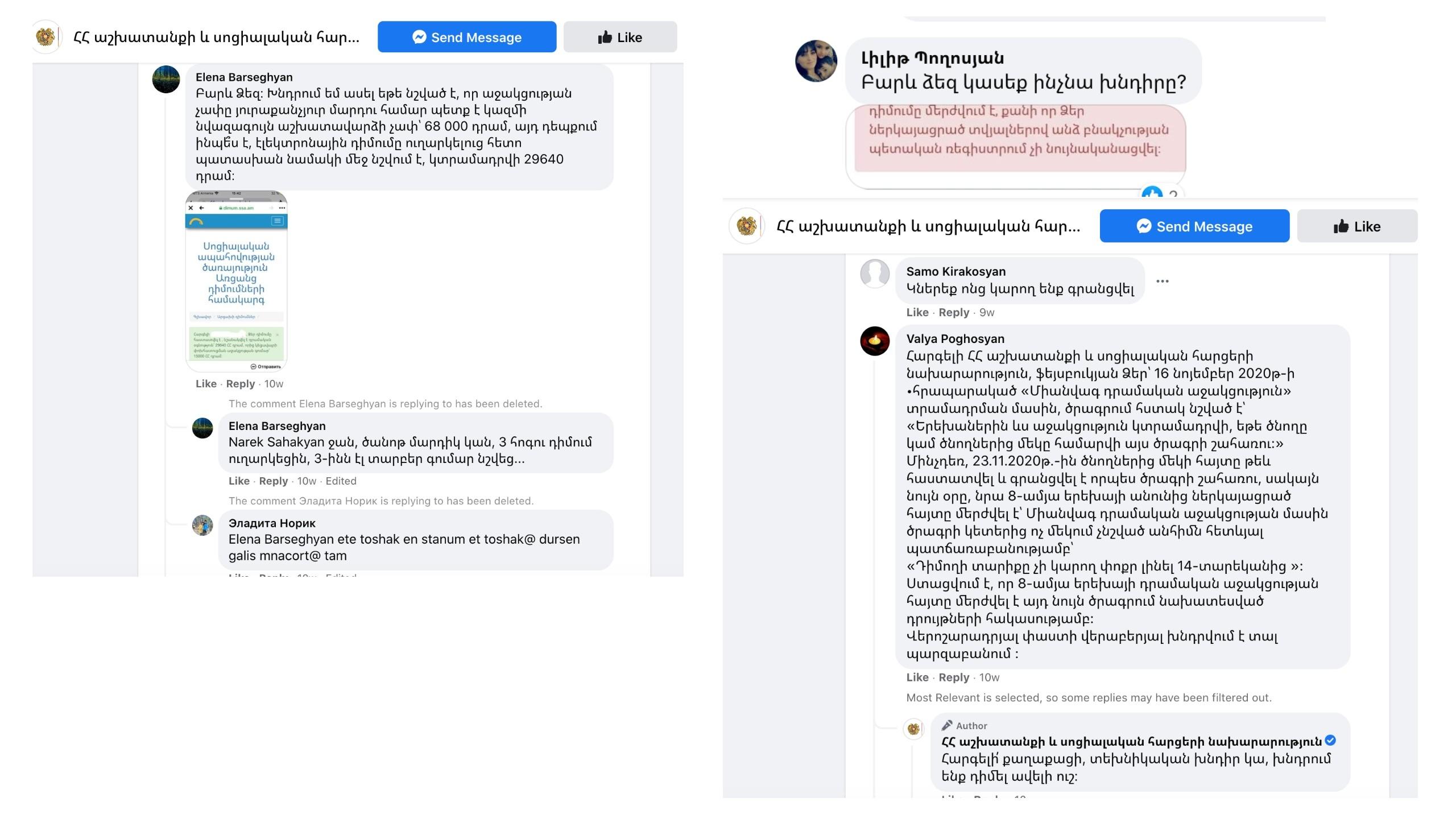

The research we conducted on the social media site Facebook suggests that there were complaints about the MoLSA for not fully implementing its duties.

For example, in some cases the state offered unfit living conditions to Artsakhtsis without considering, say, the needs of a multi-child family.

Over time, there were a growing number of complaints about the MoLSA in the comments sections.

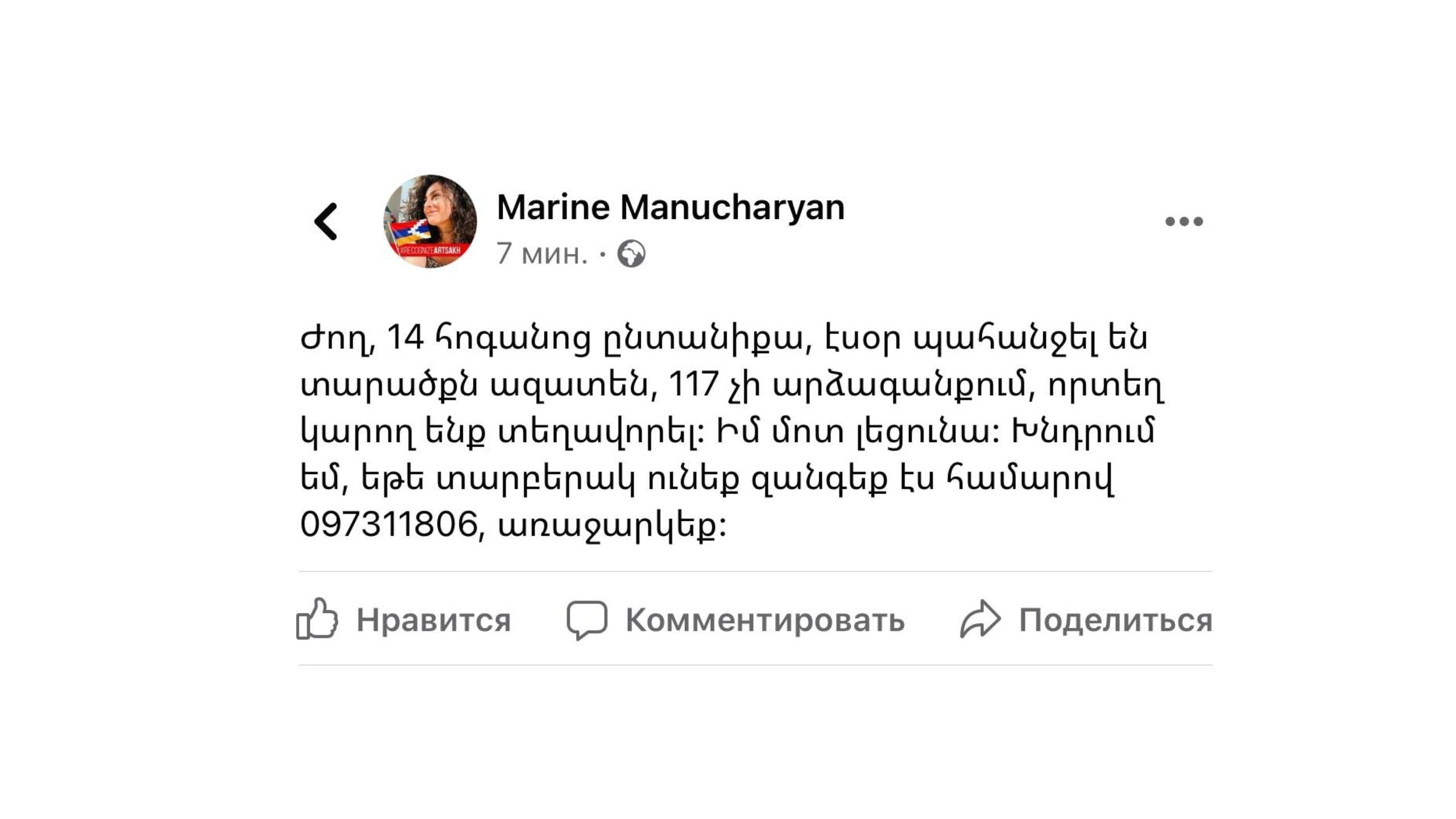

20 October, 2020

“Guys, there is a family of 14 told to leave their home today. 117 isn’t responding. Where can we place them?”

28 October, 2020

“A family of 4 from Stepanakert needs shelter. At the moment they’re at a shelter but are sleeping on the ground. They’re in Hrazdan. They’ve applied to the municipality, but there are no open spaces.”

30 October 2020 - about the hotline

“It would be good to get through to one of their numbers, not to mention that it takes days before a problem is solved – if it’s solved, of course.”

“How long do people have to sit hungry and in need, so that they help with something in ten days? They haven’t even been able to coordinate different support initiatives for the last month. Many of my friends don’t even reach out anymore, they just help, because reaching out is useless.”

On November 6th, when former MoLSA Minister Zaruhi Batoyan posted an announcement on her Facebook page that Artsakhtsis can apply to the Yerevan-based Artsakh Operative Office (phone number 81-31), one citizen responded that there is no response from the number, while another replied that, in any case, they don’t know anything.

“We know, we’re tired of calling. No one answers. They say the same thing the whole day (all operators are busy).”

“Even if they do answer, they say ‘we don’t know’ to whatever you ask.”

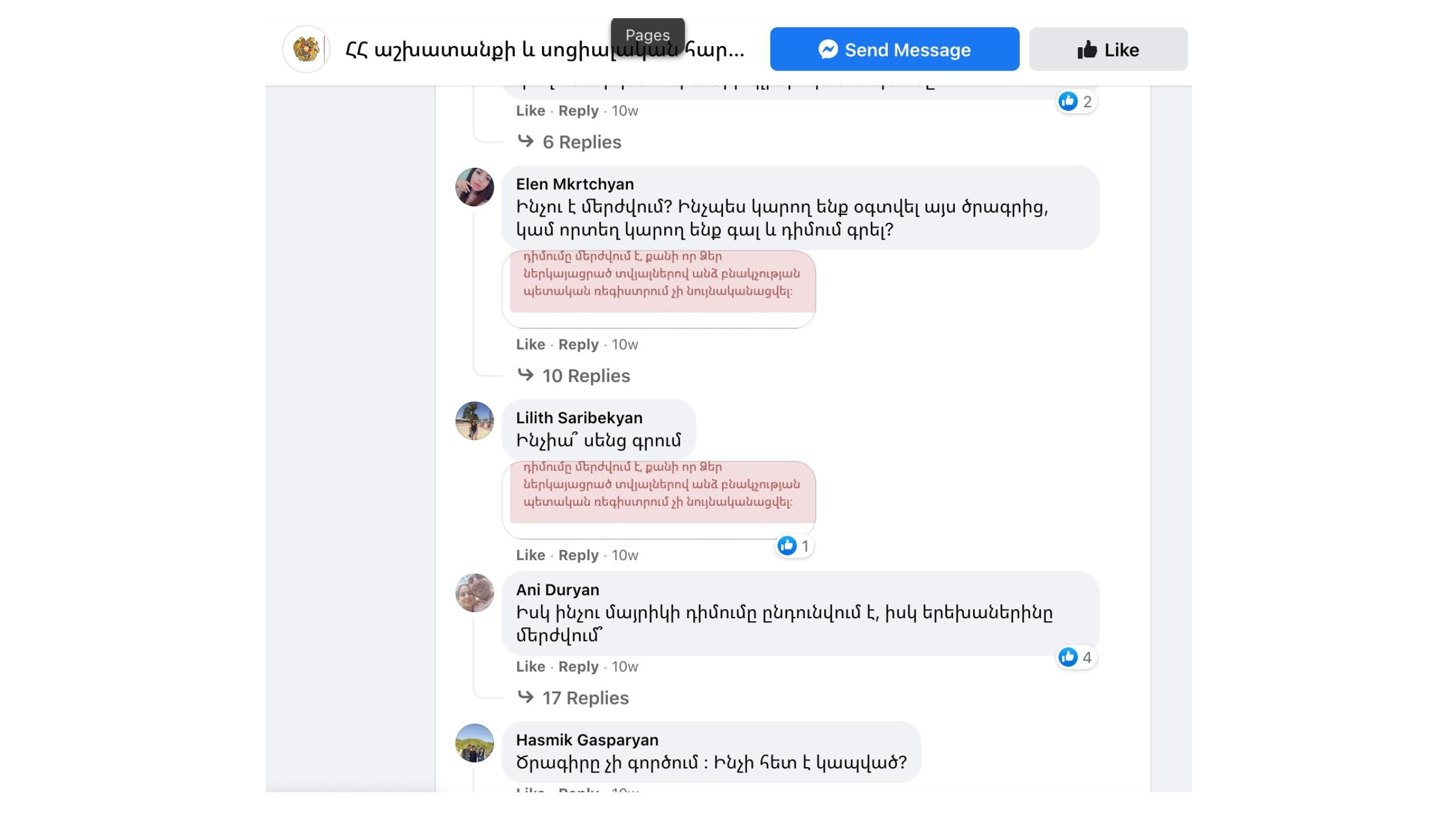

Social programs to support Artsakhtsis were launched after a decision was made on November 16th. For example, a lump sum of 68,000 Armenian drams would be given in social assistance to citizens who did not receive any salary from the state and were not of conscription age, that is 18-58 years old (in the case of men). Children would also receive aid if one or both of their parents was a beneficiary of the program.

An additional 15,000 Armenian drams would be given to Artsakhtsis who had lost real estate and who did not have any personal property in Armenia. The aid would also be given in cases when the citizen had already returned to Artsakh.

In addition, 300,000 Armenian drams were allocated to citizens from settlements beyond Artsakh’s control. Aid was also allocated to soldiers killed or wounded during the war (there are around 20 social support programs to date).

According to information we received from the Ministry, they properly accepted Artsakhtsis’ applications regarding appointments, recalculations, restoring funding rights, and payment oversight for pensions, benefits, and other cash payments. And, “in case of difficulties”, they secured the “printing and filling out of applications” and sent necessary details via email.

“As of December 7, 2021, 107,409 assistance applications for citizens registered in Artsakh have been filed. Accordingly, data shows that 73,106 people have been provided with payment, of which 72,602 received additional assistance in the amount of 15,000 Armenian drams on the basis of not owning real estate in Armenia (with the exception of land used for agriculture).

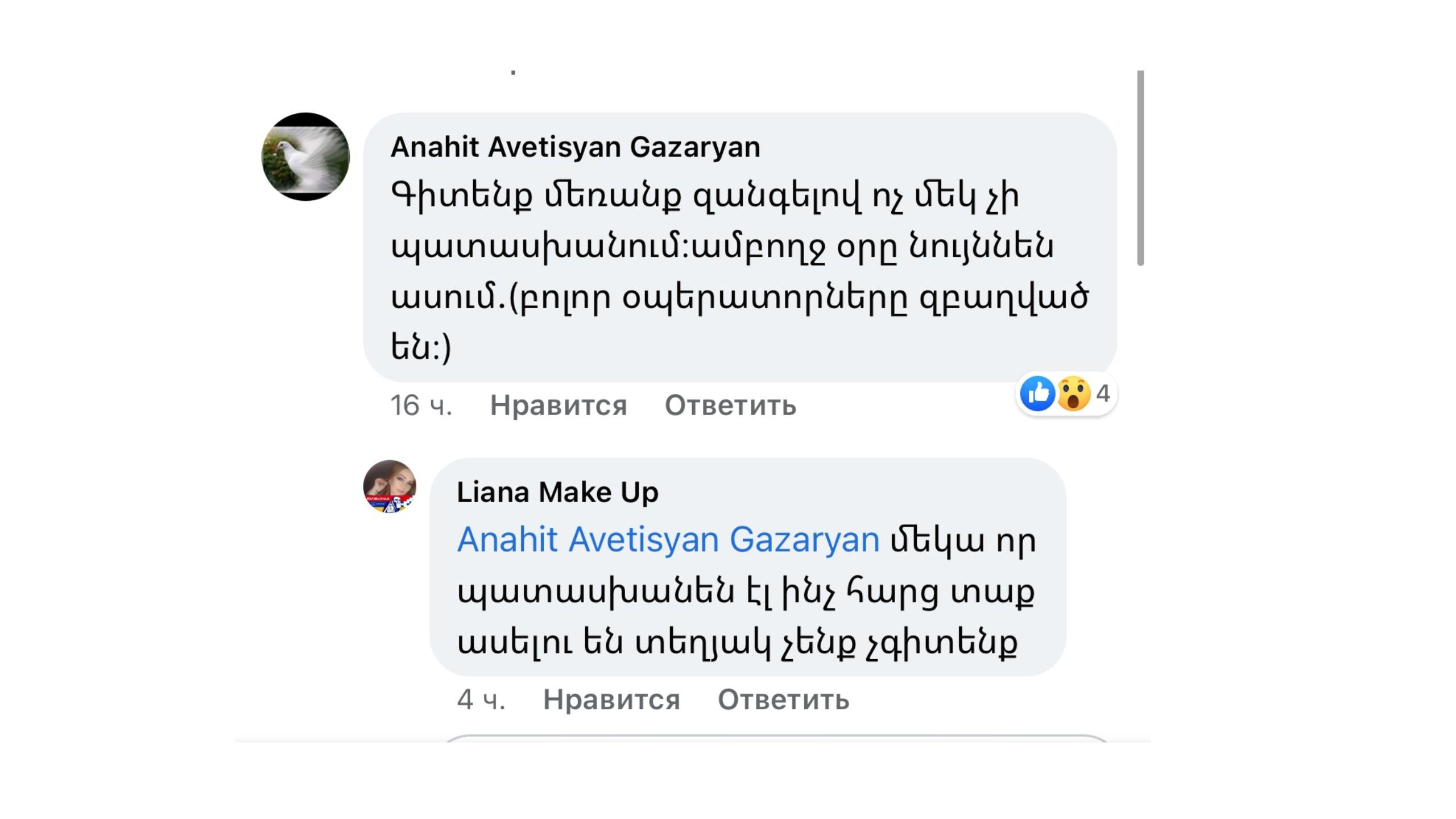

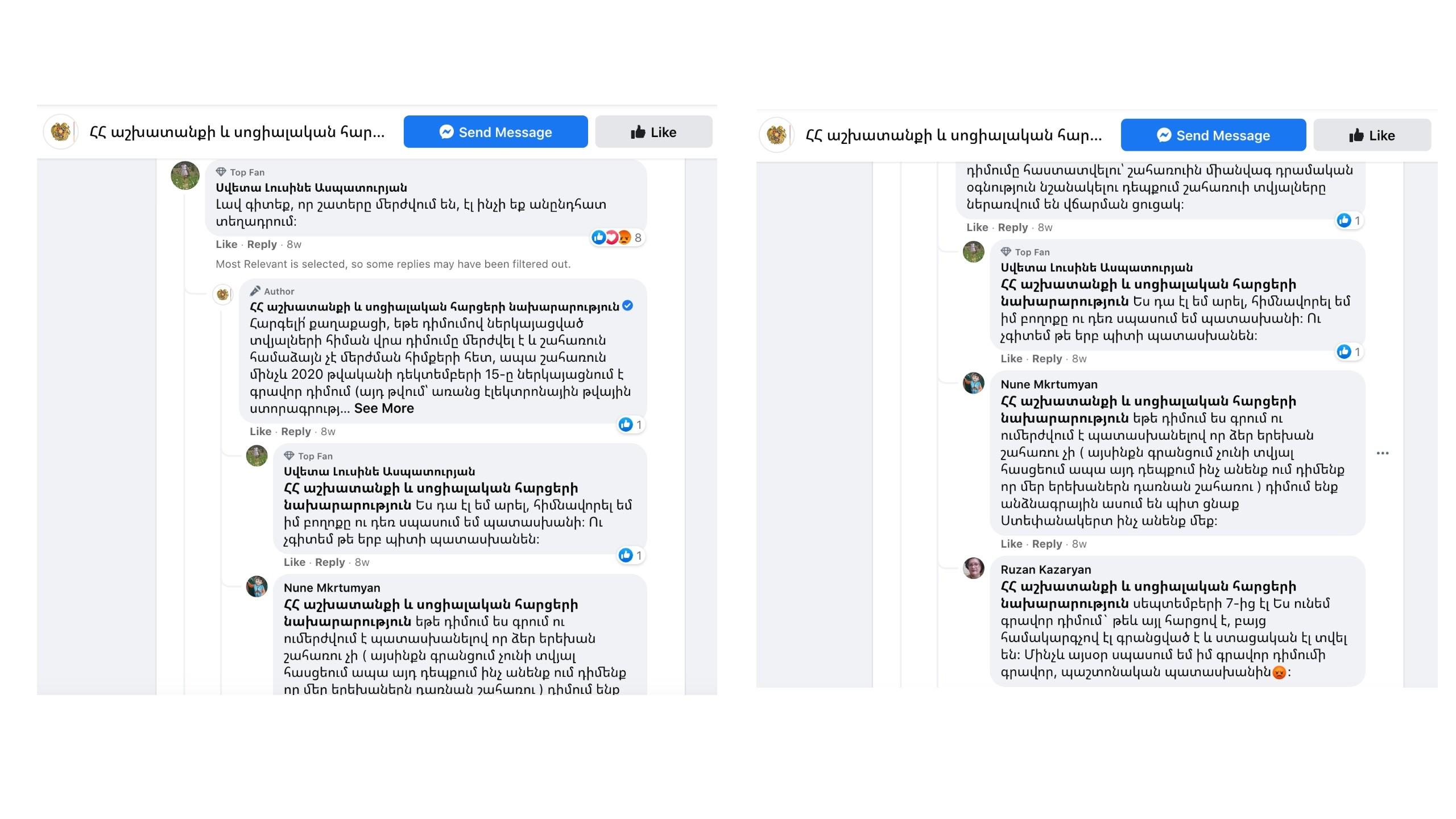

According to people’s responses on social networks, there have been many cases when applications were rejected, people did not appear in registries because of technical issues, the amount of money was minimal, or the application was rejected for inexplicable reasons.

There were an especially high number of cases in which applications of parents in the family were accepted but those of their children were rejected. To this day, there are Artsakhtsis who have not been able to receive financial aid for their minor children.

Details can be found in the comments section on the MoLSA Facebook page.

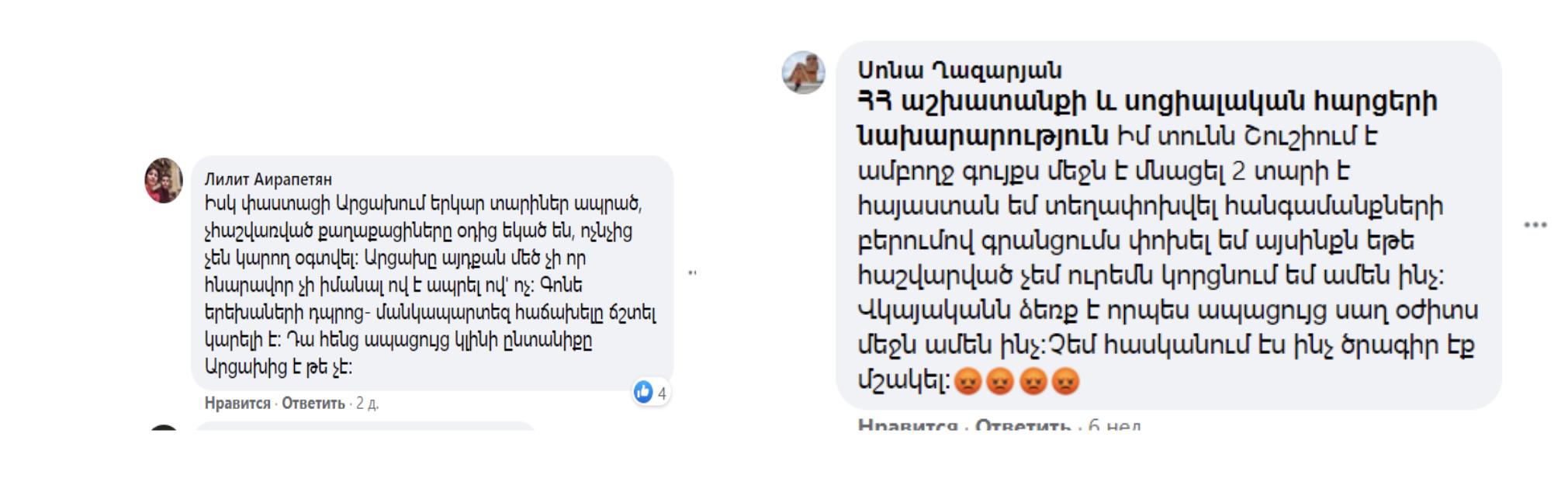

And, in some cases, people were unable to benefit from any assistance program because they were not registered in Artsakh.

Lilit Hayrapetyan: “Those who have in fact lived in Artsakh for many years but are unregistered have come from thin air. They can’t apply for anything... At least they could have checked if children were attending schools and kindergartens. That would prove if the family was from Artsakh or not.”

Sona Ghazaryan: “My house is in Shushi, all my property was left inside. It’s been 2 years since I moved to Armenia. I changed my registration due to certain circumstances. Does that mean since I’m not registered that I’ll lose everything?”

Generally summarizing our interaction with citizens, it’s noteworthy to mention that the main problem was a loss of trust due to the vague promises of programs and unclear deadlines.

State assistance to private companies

From the very first days of the war, a number of private hotels and guest houses also hosted Artsakhtsis. Some also provided them with food and took care of other needs.

In accordance with government decision number 1822, adopted on November 23rd, financial aid was given to guest houses and hotels that hosted citizens displaced from Artsakh to compensate them for “debt incurred” in October 2020. They did this by covering utility bills for natural gas, electricity, and drinking water.

For that purpose, 127,121,000 Armenian drams were allocated to the Ministry of Territorial Administration and Infrastructure from the reserve fund of the state budget.

At the end of January, we contacted around 10 guest houses that provided Artsaktsis with support to find out if they received any aid.

We were informed by the hotels that the reimbursement for utility expenses was mostly carried out, except in a few cases when the reimbursement was partial.

For example, the majority of hotels – Laguna Hotel Vanadzor, Kirovakan Hotel, Vanadzor Armenia Sanatorium, Park Resort Aghveran, Picnic Hotels, Avalon, Gayane, Old City Hotel Alaverdi, Baron Hotel, and Royal Hotel – confirmed that they received reimbursements for the months that they hosted Artsakhtsis. However, Gayane Hotel Manager Sona Khudinyan mentioned that, although gas and electricity expenses for October and November have been paid, the water bill had not yet been paid. “They said that it should already be paid, but it isn’t yet. If I were to give an estimate, the gas bill was 125,000 Armenian drams for one month and 110,000 drams for the other, and electricity was 150,000 and 170,000. The water has to be less. As far as I know, it’s 20,000 or 25,000 per month.”

Since October, more than 30 people have lived at the Hotel Qefilyan. Hotel Manager Sargis Qefilyan said in a conversation with us that the state has provided some support for utility bills but that they have personally provided their own food. “Reimbursements for electricity were made. As for food, we organized everything ourselves, though we collaborated in some cases with our benefactors. To this day, we are still hosting one family from Hadrut. They are elderly.”

Baron and Royal hotel staff member Arthur Hovhannisyan noted during a conversation with us on January 30th that the government paid all the utility bills for November but only half of the December gas bill. They are still waiting for reimbursement for the electricity bill. “The government paid 50% of the gas bill, and I paid the other 50%. As of today, they still have not paid the electricity bill. I’m waiting. It would be good if they paid it by the end of Monday. If not, I'll pay it. As far as I remember, the electricity bill alone for Baron Hotel was rather high – more than 80,000. By now, they should have already paid the electricity and water bills, as promised. We’re waiting, let’s see.”

Nairi Hotel noted that they received reimbursement for November utility bills but not yet for December and January, though they expect to receive it.

From October-December 2020, 125 Artsakhtsis applied to the State Employment Agency regional employment centers, of whom 14 were employed and 3 included in the temporary employment program.

During this entire period, the MoLSA did not receive any financial assistance from the Hayastan All Armenia Fund.

Authors: Meline Avagyan, Andranik Haroyan, Hayk Hovakimyan

Mentor: Tatev Khachatryan

Photos: Narek Aleksanyan

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment