Armenian Courts Released 38 Detainees to Fight in 2020 Artsakh War; Government Doesn’t Know Whether They Fought or Their Whereabouts

When war broke out in Artsakh last fall, hundreds of jailed convicts, and those in pre-trial detention, in Armenia petitioned the government to be released and thus join the fighting.

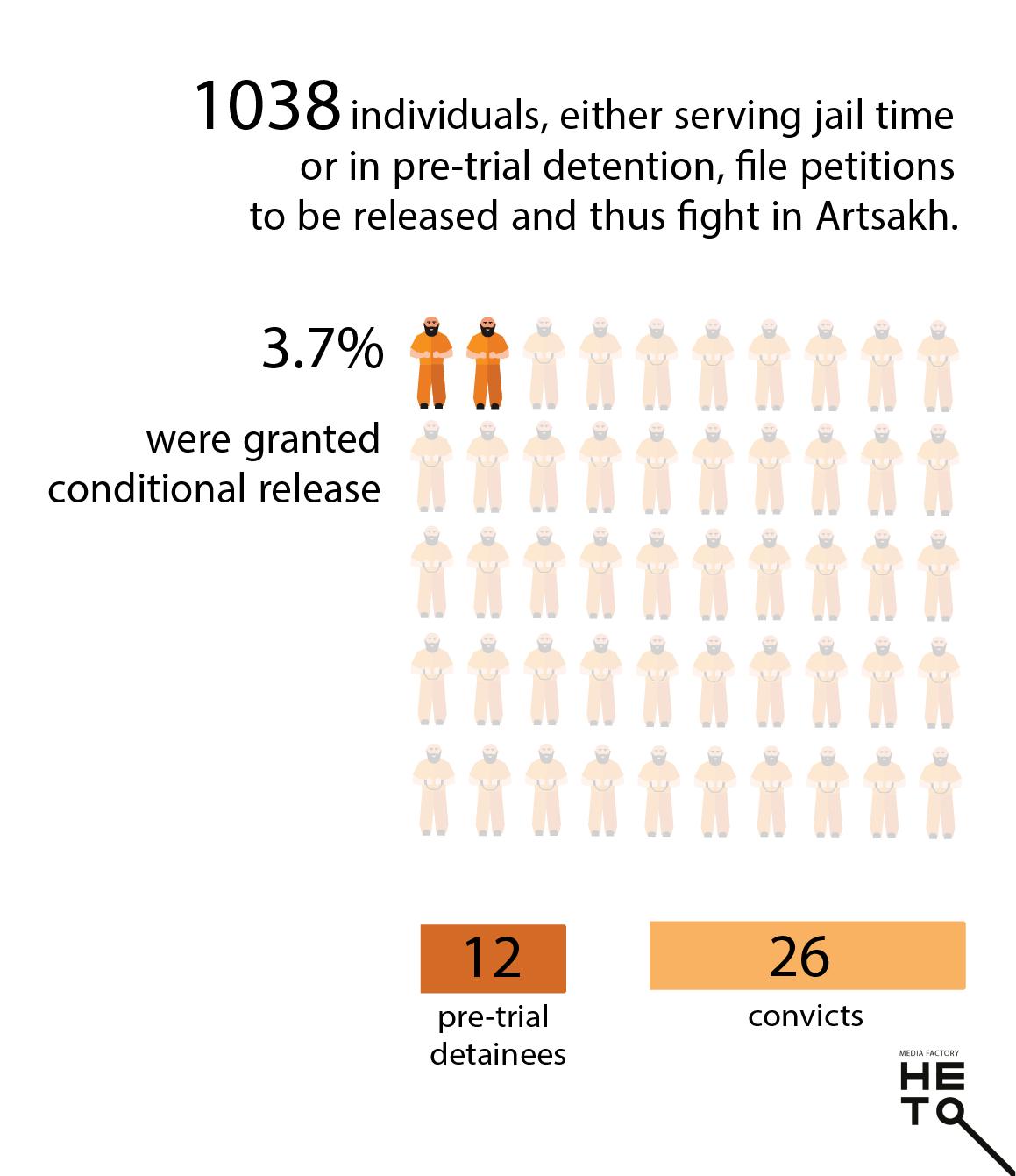

According to the information provided by Armenia’s Ministry of Justice, between September 27 to November 9, 2020, 1,038 applications were filed for some type of conditional release. 547 were convicted and serving jail time, and 491 were in detention awaiting trial.

38 individuals were released (26 convicts and twelve in pre-trial detention).

Surprisingly, no one in government can say whether any of them fought in Artsakh. Nor can they say where these individuals are today.

No public oversight of the process was carried out as government agencies did not maintain proper statistics. There were also no control mechanisms that would prevent flight risks.

Hetq investigated the legality of these release decisions. It wasn’t easy since the government agencies we talked to said they don’t keep records.

The legal bases for the regulation of the military mobilization process during martial law declared in the Republic of Armenia are defined by the Laws on Defense, the Legal Regime on Martial Law, the Law on Military Service, and the Status of a Soldier. According to the decision N 1586-N “On declaring martial law” by the relevant legal acts adopted by the authorized body developing the defense policy. There are no special legal regulations regarding convicts and detainees expressing a desire to take part in hostilities.

Did the 38 individuals released fight in Artsakh? Where are they now?

The answer to the above questions remains unknown.

The Ministry of Justice did not keep personal data (age, education, health status, suicide/self-harm risk, escape/attempted escape risk) of those released from prison/pre-trial detention to fight in the war.

It did not keep statistics on the length of their sentence or detention, their previous convictions, or their military service.

"I would like to inform you that the RA Ministry of Justice’s Penitentiary Service does not have sufficient information to answer your written inquiry,” said Tzovinar Tadevosyan, who heads the Penitentiary Service’s Dept. of Social, Psychological and Legal Affairs

The Ministry of Justice did not keep statistics on whether those released had been arrested on charges of committing another crime.

No statistics were available on whether those released had been killed or wounded in the war.

Convicts Felt Powerless During the War

"During the war, those in jail were not involved in the war effort," the Justice Ministry said in a statement.

During the war, convicts were not sewing sleeping bags, making backpacks, etc. In private conversations with Hetq, those serving time confessed that they felt powerless to help the war effort and this impacted them psychologically.

One convict, Armen (name has been changed), said that he was always tormented by the thought that while he was eating and drinking, warm and safe, others younger than him were fighting in difficult conditions. He also felt powerless, seeing the entire nation unite in the war effort.

There were also convicts whose children were at the front, and because communication with them was restricted, they suffered mental anguish.

Hetq interview 27 jailed individuals (12 pre-trial detainees, 15 convicts, 3 of whom were sentenced to life imprisonment). Not all received answers to their applications for conditional release in order to fight. It was noted that the majority did not receive any response or that the applications were addressed to various bodies, including the Ministry of High-Tech Industry.

Criminal Justice Expert: “Sending prisoners to war is a way to save money”

Under Armenian law, there are no mechanisms in place to control the recruitment of detainees to participate in hostilities, including during the declaration of martial law. There are no special rules or procedures for monitoring the conduct of defendants or those accused who have already been drafted.

Criminal justice psychologist Arshak Gasparyan notes that the practice of sending prisoners to war was widespread in other countries, such as the United States, Israel, Palestine, Russia, and others. He says that getting convicts in involved in warfare pursues two main goals. The first is to reduce the overload of state institutions, and the second is to save money.

"Not only is there no problem of overcrowding in Armenia's penitentiaries, but there is a waste of state financial resources. There are about 2,300-2500 imprisoned in Armenian penitentiaries and 2,300 penitentiary employees. Compare this to the international norm of one employee for every three four, five or six prisoners," says Gasparyan. He believes that involving detainees in hostilities does not solve any military or state problem.

Gasparyan believes that the practice of sending prisoners to the front line is conditioned by negative public perceptions of convicts.

"In war situations, public opinion holds that prisoners should be the first sent to the front line, where human life and health are endangered, thus treating the lives of detainees/convicts as subordinate to other citizens," says Gasparyan.

According to Arshak Gasparyan, state officials should not be swayed by public perceptions given that the state has an obligation to protect those being held in its correctional facilities. Moreover, prisoners, unlike citizens who are free, have limited rights and opportunities.

Another factor that does not allow prisoners to take part in the war is the demand of the victims and their legal successors that convicts serve their full sentence.

Finally, Gasparyan believes that sending prisoners to the front may contain recidivism risks. "Imagine a person who has lived in a small cell in a prison subculture for years. Have we correctly assessed the risk of immediately giving that person a weapon?” asks Gasparyan.

It should be noted that according to the Prosecutor General's Office, none of the convicts released on parole in order to participate in the recent Artsakh war has been readmitted to a correctional facility on charges of committing another crime as of January 14, 2021.

As for the pre-trial detainees, there is no information about them reommitting any crimes.

No Monitoring Mechanisms

Armineh Fanyan, a lawyer with Armenia’s Public Defender's Office (PDO), told Hetq that the PDO sat in when reviewing cases of those wishing to take part in the war were examined. These mostly involved pre-trial detainees. One case was examined for the possible paroling of a convict.

Asked what criteria were used in discussing the motions in these cases, the lawyer said that there are no criteria as such, as they are not mentioned in the legislation. They were guided by practice.

"Most of the applicants were participants of the first Artsakh war, freedom fighters who had fought during the first Artsakh war. Relevant references were submitted to the court by the Ministry of Defense, and the court was convinced that the person would go to the front in case of a change in the detention measure," Fanyan told Hetq.

Detention was lifted or replaced by other precautionary measures in cases of persons charged with serious, especially grave crimes, even attempted murder.

Fanyan says that the court, considering the situation in Armenia and the fighting in the Artsakh Republic at the time, found that the state's interests overrode the original court order for detention.

Asked whether she sees the need for legislative changes, the lawyer said that the situation with the release of a person leaving for the front has no legal regulation at all. The only regulation in this area refers to the fact that detainees are not subject to conscription. However, according to Fanyan, the existing regulations are fully sufficient to change or eliminate the issue of detention, but the fate of the case is problematic after the person goes to the front.

Regarding possible legislative change, Fanyan notes that due to specific situations, the state should create mechanisms to hold accountable those released but not yet left for the front.

According to Fanyan, the situation is different in the case of parolees, when the court has the authority to impose specific obligations on the person during the entire probation period. For example, if a person is paroled in order to go to the front, but fails to do so, they must serve out their full sentence.

Lawyer Davit Gyurjyan, co-founder of the Law Development and Protection Foundation, sees corruption risks in the process.

"In fact, if the release of a person is conditioned by the fact that he/she is provided with the opportunity to take part in actual hostilities, then this is a kind of 'bribery' a person pays to the state," says Gyurjyan.

Referring to the existing mechanisms for monitoring the behavior of released persons and their effectiveness, the lawyer notes that, in general, in those cases where individuals have been subjected to alternative pretrial detention, the authority to exercise control is given to the probation service.

And that control is exercised largely by visiting the person's place of residence or work, and vice-versa, by the person reporting to the relevant branch of the probation service.

The situation is different with a person who went to war. There are certain issues related to the scope of precautionary measures under control, the effectiveness of control methods, and so on. According to the lawyer, in any case, it is obvious that when the precautionary measure is changed under the pretext of a person participating in hostilities, these control mechanisms will not work.

Authors:

Zaruhi Hovhannisyan

Elina Gyurjyan

Hayk Makiyan

Mentor:

Grisha Balasanyan

Photos:

Saro Baghdasaryan

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment