“I became a victim of Armenian hospitality”: Hetq Talks to Britisher Who Rushed to Armenia’s Aid After 1988 Spitak Earthquake

By Hasmik Meliksetyan

After the 1988 Spitak earthquake, many people who didn’t even know where Soviet Armenia was, began to help those impacted by the disaster.

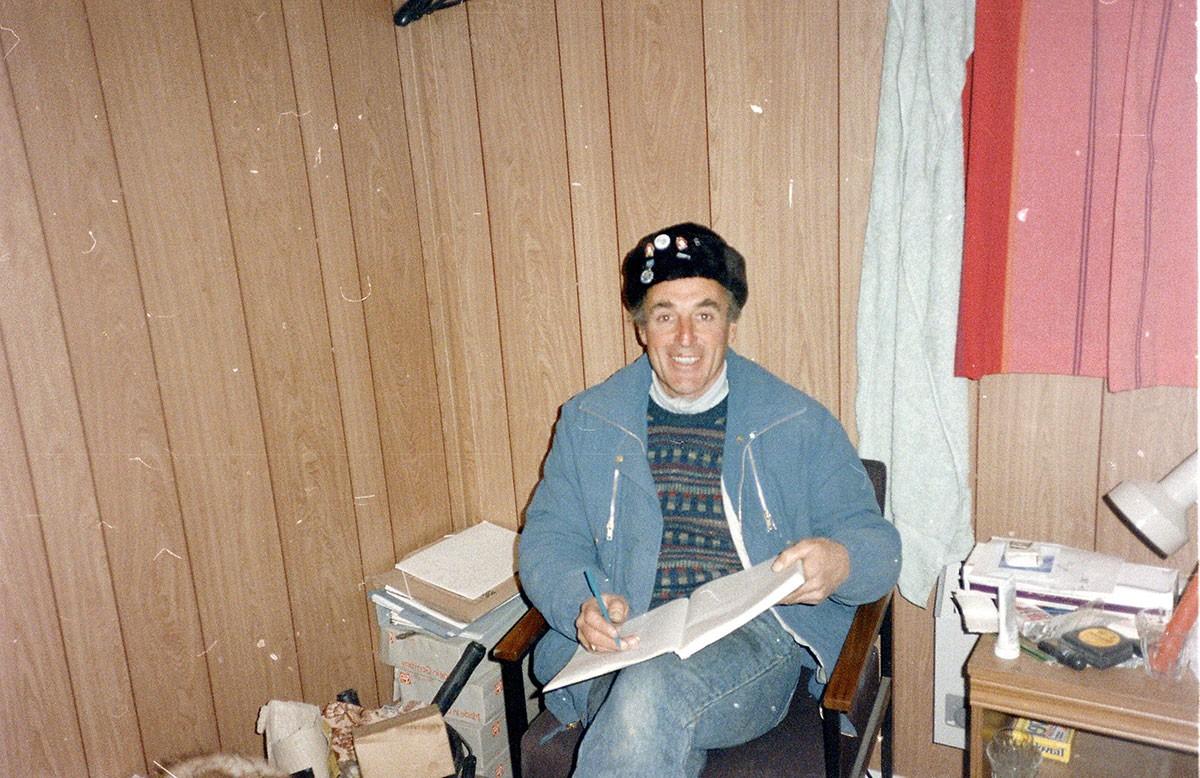

More than 113 countries got involved in putting Armenia on its feet again after that great tragedy. The Lord Byron School in Gyumri was donated by Great Britain. David Dowell and his company were suggested as partners in the school’s construction. Hetq talked to David Dowell, a Britisher who coordinated the construction. He’s been to Armenia and Artsakh 53 times in 30 years, is an honorary citizen of Armenia, and one of the best friends of the Armenian people.

Mr. Dowell, in the last three decades you've made more than fifty visits to Armenia and Karabakh. When and how did you get acquainted with Armenia?

How I got acquainted with Armenia came about simply as a result of the dreadful earthquake that took place on December 7, 1988.

On that day and in fact, for a few days after, my connection to Armenia was watching, on our TV news feeds, the awful scenes of death and destruction. It was in 1989 before I and my company became involved more directly. At that time we were one, if not the largest, roofing contractors in Europe and our prime minister, Mrs. Thatcher offered Mr. Gorbachev a British-built school to replace the destroyed English language school in Leninakan.

Things were slowly being organized and I agreed we would play a role in its building. A site visit took place, I think in February, and then detailed planning started over here. The plan was to create an earthquake-proof building using all UK-sourced material except for the external tuff stone. In truth, Armenia was a small part of the Soviet Union back then and not many people here knew much about the country or indeed where it was located. I for certain fell into that category.

Can you tell us about your visit to Gyumri (Leninakan) and Spitak?. How did you adapt to the cold winter of Armenia without basic living conditions?

Work on site started in August. Te site was cleared of the destroyed blocks of flats and made ready to receive the workers' accommodation blocks and then to fence off, rather like a prison, the entire build area.

My team was to follow the steelworkers. It was they who constructed the metal frame work and, in turn, we were to cover all the roofs with steel and on top of that deep insulation and slates. We actually started in early October. It was already getting very cold at night but well before we left the UK we were made aware of the extreme weather conditions in Leninakan so we arrived prepared. Our camp was shipped from England (it is still there or was three years ago). At the start, all we needed was coming by train from England. As the winter went on things changed.

The Azeris started stealing our materials, our food, in fact, everything. We would drive to the rail yard and open the locked container only to find they had broken in through the roof and the goods were stolen. At that time the electricity went off, the water supply failed and fuel for the machines became a major problem. Life became very tough but the British government hired a large Hungarian haulage company to drive all we needed by road from London to the school. The drive took 10 -12 days. They saved the project and the workforce.

How long did you stay in Armenia during the construction of the Lord Byron School? You probably witnessed dozens of good and bad incidents during that time. Can you remember one or two?

Since, from the start, my plan was to come out with the team, get it working, and then return home. When I saw what I saw it became impossible to run back home.

Instead, I would stay 3-4 weeks at a time then rush home for a week or two before returning to the project. My own presence there I felt encouraged the guys to progress as winter, the ice, and the snow was around the corner. Impressions were many and the very first was to see so many buildings looking just perfect only to learn that the floors within had fallen one on top of the other and killed all inside.

Then you would walk down a street and see a terrace block with maybe 2 of 5 houses destroyed and the others just perfect, it was so cruel and arbitrary the way death was allocated to the unfortunate Armenians.

Then there was the awful temporary housing. People were living in all sorts of odd containers, etc. The amazing thing was we would be up on the roof and suddenly an awful noise would be heard and a container in which people were living was being towed by an old tractor to a new more preferable location. It was witnessed so many times in those early days.

Then there were the funerals. Here, coffins are closed and never opened once the deceased is placed inside. Over there we found it difficult to view so many funerals with a face staring up from the open box. Many folks died from injuries of the quake and funerals were non-stop. One last but a nicer observation. For a year right up to December 8, 1989 the women were all without makeup and dressed in drab black clothes. We often discussed what they really looked like as they rushed past the construction site carrying their shopping or dragging a silent child or two. Then it happened - lipstick, make up- bright clothes. It was a real transformation, and the first time any of the men had seen Armenian beauty. It was a good day for sure!

I know that besides the construction of the school, you have provided huge assistance to Spitak and Gyumri. Can you tell us about that support? Which directions did you pay special attention to? And finally, how could you find the money for help?

Throughout the build time all the British workers would arrive in Armenia with pens and sweets for the children, it was small in value but meant a lot to the little faces that stood pressed up against the wire fence saying pen, pen, pen, pen until one or other guy succumbed and made one or two happy, at least for a while :-) The real start for me was seeing how bad things were in every regard. On my second or third trip, I carried a sports bag of my own children's clothes that had become too small. The people of my village noticed I was away for long periods, questioned what I was doing and on learning of the clothes I had carried announced they too wanted to help and so it was that one sports grip became two, became four an on and upward into container loads. From 89 to 94 everything I collected went to Gyumri and the containers were financed by AGBU, the diaspora, companies that I had written to seeking their help, and of course from Felicity and myself, each container cost $6000 at that time. Clothes turned into everything, from motor cars, computers, medical items, copper pipes, toys, and anything I was able to beg from folk over here.

I know, that you were at the opening ceremony of the school. How did the event go? For the first time, Armenia hosted the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Margaret Thatcher. Did she like the school?

The opening was truly a magical day. In those days we were forbidden by the Soviets from using the local airport. We had to get to and from Yerevan many times on bad roads over the hills.

There was no problem for Mrs. Thatcher. She arrived in a Royal Airforce jet that landed at Leninakan airport. The entire length of road, from the terminus to the school, was miraculously paved in new asphalt.

The initial plan was for both the Russian leader and Mrs. T to open it together but the Armenians had fallen out of love with Mr. G and it was decided he was best left in Moscow, She was treated like God by the locals as were all of the government officials. The crowds caused her to be very late arriving at school and I well recall nearly dying from the heat while sitting in the gym waiting. We, the management team, had been told to wear a jacket and tie, not the right clothes for that terribly hot sunny June day.

We all had a chat and photos with her and her husband Dennis, a great man, who told the KGB just what he thought of them as they tried to rush her into her car after she had conducted the opening. It was very funny and is to be seen on my videos you will receive.

In the 1990s you were in Spitak as well. What was the purpose of your visit?

Initial visits to Spitak wweren't about assistance. The first time I went was on a rare day off from work during winter. I took the camp minibus and 12 workers to go and see the damage in Spitak for the first time. We all became victims of Armenian hospitality.

I think you know that story from when I first met you and showed the family the video of that time. The Armenians got all my men drunk and well-fed. After a year or two, the town was supplemented with goods being delivered to a priest whose name escapes my memory. It was mainly clothing items and a few computers.

Was it difficult for a person educated in the West to work in Soviet Armenia? What challenges did you encounter?

It was not difficult at all but highly embarrassing. Why?, I hear you ask. Simply put, the knowledge of our language, our writers, our poets, our musicians, and even some of our history eclipsed us so often. As for work, it made little impact as we were very much locked in and the Armenians locked out. The exceptions were the interpreters and one or two visitors of importance.

How is it that a British man, who had very little information about Armenia, became such a devoted friend of Armenia and Armenians?

I had been fortunate. Like many there I was born in bad times. Our toilet was outside, down the garden. We had no hot water, no central heating, so I found it easy to turn my mind back to my own dark days.

Post-war Uk was not an easy place to live and so it was for the Armenians. But they had an earthquake to add to the woes of life under the Soviets. I just fell in love with the place, the people, the food, and the family unity and wanted to try and help. It was a mere drop in a big lake but made me feel I was doing something to help.

In one of your interviews, you said: "I became a victim of Armenian hospitality!" How do you see Armenia?

A victim of Armenia hospitality, so easy to be captured and I was.

A nation that was so keen to give what little it had. I do not recall ever having a problem. Just two very quick stories to illustrate my point.

The first was in 1990 and I was at the Lord Byron School because we had a report the roof had a problem. I was accompanied by one of my men and found a car that would take me back from the school to Zvartnots Airport. It was the practice then to hang around the market and beg someone (there were few cars and even less fuel to be had) to take you back.

As always I could speak no Armenian and the driver no English. I Knew the road well and when we came into Ashtarak he turned off and took us to a small bungalow. Both Michael and I smoked Marlborough cigarettes and he took our two packets, emptied the cigarettes out onto his table, and tore the cartons into tiny pieces which he used to heat the coffee. Two packets of cigarettes provide the perfect amount of flame for two coffees, it was this man's way of expressing gratitude. We did not miss the plane. It was close but we made it on time.

When people knew we were English, just one packet of genuine American or British cigarettes covered the fare. They would take us in those days over the mountains at no charge. I was alone and I was heading to Leninakan. I found a car by the cinema in Yerevan and using sign language secured a lift on my own. I always filled my coat pockets full of cream-filled chocolate eggs to give to children when I saw them.

Again using sign language, I showed my wedding ring and tried to establish if he was married. He gave me a "haha". Next was - "have you, children?" Four fingers meant fou,r so I extracted 4 eggs and passed them over. He passed them back without explanation. So the eggs went back and forth in his old rotting Lada.

And then he turned right and off we went up into the hills where this strange Englishman was shown off to neighbors his wife and kids summoned to meet me. I think the entire village was told my friend had captured me since so many came along to view me.

His plan was first for me and not for him to present the kids, his kids with the eggs, and then to come into the house where his wife was rushing to produce a meal for the unexpected guest. Yes a victim of Armenian hospitality.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (1)

Write a comment