Smbat Byurat: Europe, the Eye of Reforms, the Armenian Nation, the Power of Reforms... (Part 1)

The Titanic's Zeytun passenger

That day, before heading home, Smbat Byurat stopped by the Reuters news newsstand to catch up on the latest foreign news.

The first headline he saw read: 'Titanic, Dead.'

The shock overwhelmed him-he lost consciousness and was rushed to the hospital. His mind was torn between the passengers lost in the icy waters of the Atlantic and his own family, who awaited news he did not know how to deliver.

The sinking of the Titanic was deeply personal to him. His son, Vaghinak, had been aboard that massive ship, making his way to America. With a capacity of 47,000 tons, the world's largest ocean liner embarked on its maiden voyage on April 10, 1912, and was expected to reach its destination safely. Now, that hope was gone.

Smbat agonized over how to break the devastating news to his wife and daughter-in-law, Vaghinak's wife. As he drifted in and out of consciousness on his way to the hospital, he found himself rehearsing the words that would mask his grief.

'My sister died in Zeytun,' he would say."

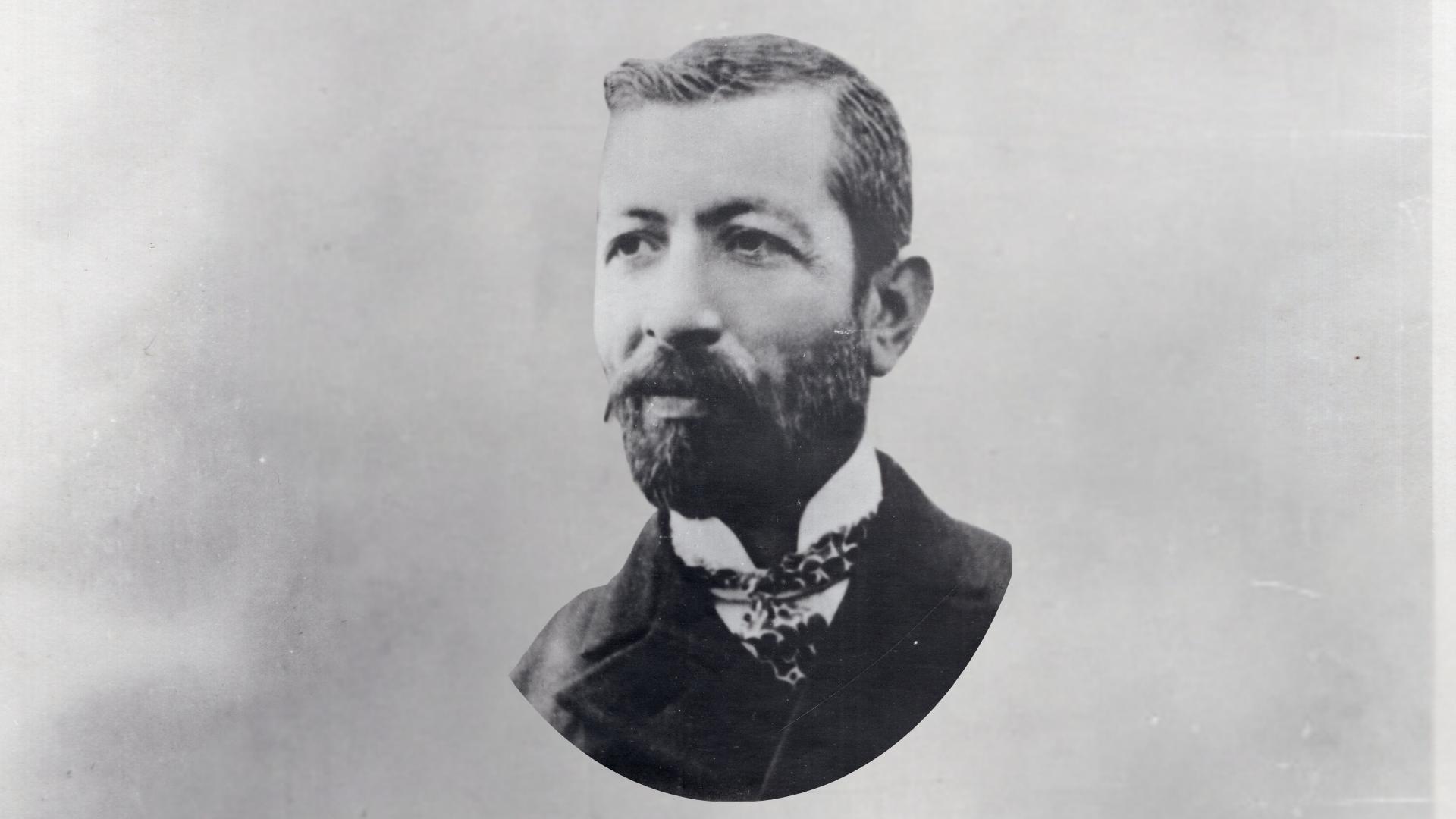

Smbat was a native of Zeytun, and his original surname was Ter Ghazarents. In 1895, during the reign of Sultan Hamid, he was arrested and exiled from Zeytun due to his political and public activities—he was a member of the Hunchakian party. Until 1909, he was forbidden from returning to his birthplace, though by 1912, he had been elected as a national deputy for the Zeytun-Marash region, granting him the right to move freely.

Yet he chose to conceal the devastating truth from his family by fabricating the news of his sister’s death. He desperately hoped his wife wouldn’t suggest, 'Let’s go to the funeral.' To reinforce his deception, he went a step further—draping the house in mourning by replacing the curtains with black and holding a memorial service.

It required immense courage and resilience to carry such an unbearable secret, yet Smbat endured. He was a man of extraordinary strength. Had he not been, he would never have accomplished all that he did for his people.

The heir to the ancient City Ani’s dynasty

Finally, who was Smbat Byurat and why should he be remembered with gratitude?

Byurat's family traced its origins to Ani. The Ter Ghazarents were among the first immigrants to leave Ani, eventually settling in Cilicia. On March 3, 1862, Smbat was born in Zeytun. His father was a priest in the Bozbayir district of Zeytun, continuing a long-standing family tradition-priesthood was a hereditary duty among the Ter Ghazarents men, and he was the 19th in this lineage.

However, Smbat chose a different path, pursuing philology and pedagogy. He first studied at the Zharangavorats College in Jerusalem before continuing his education in Paris at the Sorbonne University, where he enrolled in the Pedagogical Department.

Byurat's name is not well known in modern Eastern Armenian society. However, his work and contributions to addressing the challenges of the Armenian people are significant. Byurat left behind thousands of pages depicting the realities of Western Armenian life, particularly documenting accounts of the struggles for survival in Zeytun and Sasun. These writings not only present historical events through the testimony of an eyewitness and active participant but also provide invaluable ethnographic and daily intricacies about the inner lives of both Armenians and other nations and tribes connected to them, whether Muslim or Christian. Instead of focusing on literary and artistic expression, these extensive pages hold significant documentary value.

At just 19 years of age, Byurat embarked on a vigorous national and public mission in his homeland. He took on the role of school director in various cities across Cilicia, founded the 'Guardian of Cilicia' organization in Marash, and undertook a highly important and secretive task—the census of the Armenian population.

The brave men of their own borders

In 1880, Smbat adopted the pseudonym Byurat, a name that has been passed down through generations to this day. The name endures, but their house in Zeytun does not. Nor does Zeytun itself.

First came the devastating fire of July 26, 1887—deliberately instigated by the Turkish authorities. This once-impregnable city, which had consistently risen in rebellion against Turkish oppression since the early 1880s and emerged victorious, was set ablaze. Unable to subdue Zeytun by force, the Turks resorted to fire. Yet, even this destruction did not break the spirit of its people.

Zeytun, as its residents proudly called it—continued to resist. Through heroic self-defense, Zeytun managed to maintain its semi-independent status, serving as a beacon of courage for Armenians everywhere. Armenian intellectuals and revolutionaries found inspiration in Zeytun’s defiance, and its resistance awakened even those who had grown numb under Russian rule. Zeytun’s bravery filled Armenian history with glorious victories.

But in 1915, it fell.

A new way to kill: vaccines

In the 1890s, unable to overcome the defiance of the Zeytun people, the Turks devised a long-term plan, looking 10 to 15 years into the future. Under the guise of a public health initiative, the governor of Marash arrived in Zeytun with a doctor, claiming they were there to vaccinate children against a dangerous disease.

'Hekim Apojan—real name Doctor Hakob Kalbagjian—with his piercing eyes and large, unsightly nose, listened with bowed ears, his gaze sweeping over the terrible scene of the innocent lives that would soon vanish under his hands…' writes Byurat in his novel Prison to Prison.

Only Armenian children, aged two to eight, received the vaccine from their compatriot doctor. The following day, grief consumed the city—554 children were buried in Zeytun during the next 2 weeks.

"For a pittance, the traitor Hakob Kalbagjian, the doctor-turned-executioner, wiped out a select generation of warriors."

Before the fire, Byurat served as the general inspector of 36 schools under the Armenian United Society. After the fire, he left Zeytun and moved to Constantinople, where he collaborated with Grigor Zohrap, Hrant Asatur, and Yeghia Temirchipashyan to publish the periodical Earth.

The real reason for his departure, however, was a deepening conflict between him and the local Turkish authorities. Though he relocated to Constantinople, he still had opportunities to return to Zeytun—at least until 1895, when the Turkish rulers officially declared him persona non grata.

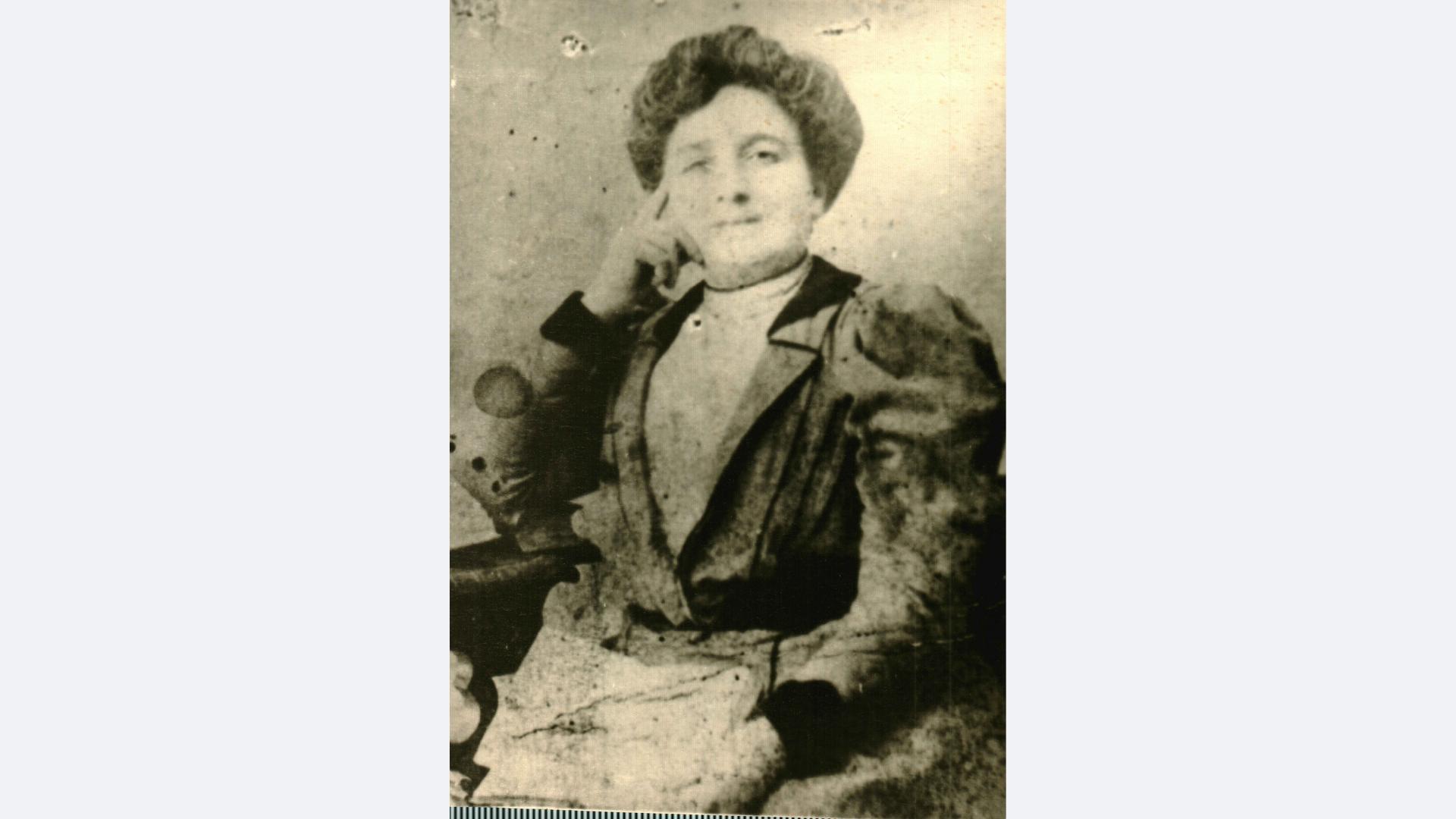

In 1884, Smbat married Yevdoxia Shishmanyan, a teacher at the Galfayan orphanage in Khasgyugh. Together, they had a son, Vaghinak, born in 1886 in Zeytun—the same child who would later board the Titanic.

At just a year old, Vaghinak was already accustomed to a life of constant movement, traveling from one city to another with his parents. The reason was twofold: Smbat’s work and his deep sense of national duty—along with the ever-restless spirit of an Armenian. As a teacher, it was his mission to establish and lead schools. He carried out this duty in Thrace, then in Samsun, and elsewhere. Wherever he went, both children and parents affectionately called him Esteemed Effendi.

Yet, teaching was not his only calling. Though pedagogy was his true vocation, the times, the national struggle, and the political climate demanded more. Like many Armenian intellectuals of his era, he was drawn into political activism. He joined the Social-Democratic Hunchak Party, a decision that soon made him a target.

In 1890, on his way to Zeytun, he was arrested in Marash due to his political activities. It was his first arrest—but not his last. This time, he was imprisoned not only with his wife, Yevdoxia, but also with their four-year-old son, Vaghinak.

Birth in prison

Yevdoxia was expecting their second child. Years later, Byurat would recount this and other imprisonments in his memoir Prison to Prison.

Without trial, both Smbat and Yevdoxia endured severe torture. Four months after her arrest in Marash, Yevdoxia gave birth to their second child, Hayk-Levon, inside the prison. Shortly after, she and her sons were released, while Byurat remained imprisoned in Marash for another year and a half—still without trial. He was then transferred to Aleppo, where the court sentenced him to five years in prison. Yevdoxia, however, was acquitted and walked free with her newborn son.

But her so-called freedom came at a heavy cost. Separated from her husband, she lived with constant longing and anxiety, while the physical toll of the torture she had endured led to a slow and tragic decline in her eyesight. Yet, despite her failing vision, she was forced to work to support her family. An exceptionally skilled tailor, she sewed tirelessly under Ottoman rule in Aleppo. Every snip of the scissors, every threaded needle, carried her thoughts back to her beloved husband behind bars.

Determined to help him, Yevdoxia soon found ways to establish secret communication between Byurat and the outside world. Ambassadors and consuls from European countries, accredited to Sultanate Turkey, began applying pressure on Sultan Hamid regarding political prisoners. To maintain long-distance contact with international institutions, the Byurats even involved their eldest son, Vaghinak, in a covert operation.

There was no time to hesitate. At that moment, their son—despite the danger—was the most reliable intermediary. But the threat looming over Zeytun was even greater, an impending disaster that overshadowed even their own peril.

To serve Armenia means to serve civilization. W. Gladstone

Determined to save the prisoners of Zeytun from the death penalty, the imprisoned Byurat resolved to contact the British Prime Minister, Lord Gladstone, at all costs. To accomplish this, he sought the help of Nikoghos Ter Margaryan, the translator at the Royal Consulate. Margaryan’s English wife had already played a crucial role in informing Ambassador Philip Currie about the Turkish atrocities, pressing him to demand restraint from Sultan Hamid.

Now, Byurat had to get a letter to the British government—but how could he smuggle it out of prison? This was a pressing question, and soon, he found not just one but two possible solutions.

The first involved the prison cook, an Armenian inmate named Grigor—though everyone in prison knew him as Gugur. He had been imprisoned for killing a Turk who had attempted to violate an Armenian woman’s honor, an act he never regretted, considering it both masculine and patriotic. Occasionally, Gugur prepared keofte, a beloved dish among the people of Zeytun. Seizing this opportunity, Byurat wrote reports in French on thin sheets of silk papyrus, detailing the dire situation of the Zeytun prisoners. He carefully wrapped the notes in wax paper, concealed them inside the keofte, and had them sent home to his wife.

Yevdoxia would then extract the hidden reports and deliver them to Nikoghos Ter Margaryan. From there, Margaryan passed them on to the British consul, who relayed the messages through diplomatic channels straight to Gladstone. Thus, the British government learned of the Zeytun crisis, the fate of the prisoners, and Hamid’s crimes through unofficial means.

What is remarkable is that Lord Gladstone personally responded to Byurat, assuring him that he would take action regarding the political prisoners. And he kept his word. Gladstone founded the Anglo-Armenian Association, igniting pro-Armenian sentiment within British society. By 1895, through diplomatic pressure applied by the British ambassador to Turkey, Hamid was forced to grant amnesty to Zeytun’s political prisoners.

As for how Lord Gladstone’s response letters made their way back to Byurat—that is a story later told by his eldest son, Vaghinak.

Secret operation: "oogh, oogh"

Vaghinak became the second means of secret communication between the prison and the consulate, the first being the Zeytun keofte.

Years later, Vaghinak, who was barely nine years old at the time, recalled:

'My mother had trained me. When we went to visit my father, I would say to him, "Dad, my stomach is hurting - oogh, oogh". My father understood immediately. Taking me to the toilet, he would retrieve the notes tied to my stomach and replace them with new reports.'

But their secret was soon betrayed—by an Armenian informant. Prime Minister Gladstone’s reply letters were discovered in Byurat’s cell. He had only one month left until his release, but this discovery led to an extension of his sentence by another five years.

However, the amnesty secured through Gladstone’s efforts also applied to Smbat Byurat. With his release, a new chapter in his life began.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (3)

Write a comment