The naked body and the national landscape

According to Kenneth Clark, landscape painting was not only the chief artistic creation of the 19th century, but also became the dominant art. Whereas the naked body, which in various periods allowed artists to communicate certain ideas or states of feeling, gradually loses impact, turning into an end in itself in the 20th century art. Concurrently the prevalence of female nudes over male ones in fine arts continued to steadily increase, becoming absolute already in the 19th century.

As for Armenian artists, the naked body is an extremely rare occurrence in their works. In the beginning of the 20th century and particularly in the 1920s landscape painting was their preferred means of artistic expression. I intend to demonstrate that the landscape and the body of a naked woman were not only placed in the opposing poles of Armenian fine arts by their significance, but also, under the imperative of the specific logic of constructing contemporary cultural identity, the national landscape has somewhat appropriated/absorbed the female body, even when the latter is not represented in the landscape.

In his book The Nude: a Study in Ideal Form Kenneth Clark traces the historical-geographic progression of the naked body through from antiquity through the 20th century. In the chapter entitled The Naked and the Nude he elaborates on the difference that exists in the English language between these two notions: “to be naked is to be deprived of our clothes, and the word implies some of the embarrassment most of us feel in that condition.” Such a body is described by Clark as “huddled and defenseless.” Whereas a nude is “a balanced and confident body: the body re-formed.”

This distinction became one of the first targets of criticism aiming at the book. Notwithstanding the fact that nudity thus defined may inspire unmodified competence over one’s body, it is understandable that “the body reformed” results from external compulsion, it is defined through the gaze of the Other, while “balance” and “confidence” are labels that are customary in the social milieu and are acquired by the body. Jean Baudrillard describes a mannequin as a focal point of ascribed significances, a result of divergent practices or discourses as applied to the body. This is how the process of socialization affords the body with yet newer marks that are recognizable and open to perusal and interpretation.

The main axis of subsequent criticism of Clark’s approach may best be characterized by a quote from one of the proponents: “His freely stated admiration for the unclothed female form … is entirely unburdened by any notion of the politics of vision,” while “separating the nude from discourses about power and the politics governing differences of class, gender and race.”

Ways of seeing, politics of vision

Clark almost completely evades reflections on the economic, social and ideological aspects of art, ignoring the fact that the “ways of seeing” were never immune to politics. Ways of Seeing is the title of John Berger’s 1972 book, where he draws attention to the ideological substance of Western art, demonstrating, in particular, the close linkage between landscape panting and capitalism. He then goes on to highlight how the portrayal of women in European art contributes to subjecting them to men’s vision: “One might simplify this by saying: men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” And, finally, he focuses on the fact that the conventions of female representations in oil paintings prevailed in the pornographic magazines of the time.

The 1968 events in Paris provided a mighty boost to criticism that subscribed to new principles. In an editorial to one of 1969 issues of the Cahiers du CinemaJean-Luc Comolli and Jean Narboni laid down the principles of new criticism. This was a farewell to the past of film theory and a transition to criticism based on sound theoretical foundations, that accessed the ideological substance of cinema. The their approach was based on the revaluation of Marx’s and Freud’s teachings by Louis Althusser and Jacques Lacan. As another critic put it, notwithstanding all hardship and crises, “Having once eaten ‘the apple of theory’ there was no going back to a pre-theoretical Eden.”

Movies are not just neutral representations of reality through the use of visual code. They are active in creating particular representations of reality. “Analysis would then call into question the reality so constructed, showing that its representations were historically contingent and that the mode of representation had effects of domination and subjection through its implication in power relations” (Robert Lapsley, Michael Westlake).

Laura Mulvey’s article (Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, 1975, Screen) was instrumental for the subsequent development of film criticism. According to her narrative cinema was inscribed with patriarchal discourse, which was most obvious in the way males – within the film and as spectators – were given a privileged, active gaze that reduced women to passive images. Women’s primary roles were to be looked at and to ‘look good’, and the scopophilic (the pleasure derived from looking at others as erotic objects) aspect of voyeurism was served up for men). These principles and the critical toolkit developed for films were gradually put to use in other forms of art.

Woman in the national landscape

According to Igor Kohn, the most general feature of the Russian body canon and the sexual-erotic culture that is closely associated therewith it is the divide between the daily routine behavior and its verbalization and representation in the “high” culture. Orthodox religious rules strictly controlled the representations of a naked body, and this state of affairs also spread onto lay Russian art. The relative liberalism in the representation of the naked body in the early Soviet years of the beginning of the 20th century was officially terminated in the mid 1930s. The Bolshevik “sexophobia” made it impossible to portray a naked body. The athletic and heroic bodies of Soviet PhysKulturniks (of both sexes) were idolized instead, to be found, among others, in Soviet avant-garde photography. Nevertheless, the academic tradition of drawing nude models, a practice adopted by Moscow art schools by the end of the 19th, beginning of the 20th centuries, quite paradoxically survived.

It was not only the official Soviet ban, neither patriarchal ethnic traditions, that made Armenian artists ignore the portrayal of nudes. I believe that there exists a more profound explanation that I referred to in passing in the beginning. The 19th century was not only the period of consolidation of capitalism, something to which Berger ascribes the domination of the landscape, but also of the emergence of nation-states. There are many studies on the geography of national identity, which reflect, for example, on how certain landscapes turn into identity landmarks that people may identify with. Mountain Ararat, together with a part of its valley has long become for all Armenians such a landmark, moreover, a landscape. And as such it as early as in Soviet times, it became an item of mass consumption. This role may also be reserved to generalized landscape compilations (a whole group of canvasses by Saryan in the 1920s attest to this).

Such a landscape, as well as the naked body, become cashes for the accumulation of symbols, a geography laden with meanings. Trough landscape the nation is settled in time and space, acquires reference points therein, at the same time representing the past, embodying the present and pointing towards the future. This is how the landscape signifies the continuity of the existence of the nation, its staying power. The involvement of viewer into the symbolic national space evokes emotional identification with a particular locale, which may be internalized, personalized as the motherland. Thus the landscape, permeated with specific meanings and values and visualized in recognizable forms, allows establishing an “imagined community,” brought together by a sense of belonging.

As a rule the new identity of a nation that acquired independence is formed on the basis of patriarchal relations. And while the masculinity is affirmed as the predominant axis contributing to collective identity, the female identity is defined by motherhood, femininity, obedience and other traditional properties. Similar to the working class or a colonial nation, the woman is considered culturally inferior, standing closer to nature, therefore the landscape, as a part of nature which embodies the essence of a nation, may identify with women.

Let us consider several examples. These are two quatrains from a well-known poem (1880) by Hovannes Hovanessian, written after Goethe (Tell me, have you seen my fatherland?).

Have you seen the hills

Where perennial spring blossoms;

The gardens awash with green,

And grapes ripening like pearls?

And have you seen its precious treasure:

Standing tall with a face of an angel,

Daughter of the South, eyes enchanting,

An unfading smile on her rosy lips?

This poem is better known to us through a parody (1910) by Hovannes Toumanian:

Have you seen the hills

Where perennial spring blossoms;

Where the alien and your own kind ravish equally,

And tears and blood are abundant?

And have you seen its precious treasure,

Daughter of the South, a miserable creature,

The seal of silence on her lips,

Totally abandoned to filth?

The first is an Arcadian landscape, compliant with every rule, where man and nature exist in primordial harmony, a Golden Age idyll transformed into a nation’s very own paradise. Toumanian’s interpretation, full of anti-colonial pathos and underscoring class inequalities, draws from the components of the enlightenment and progressive discourses. In both cases, that is, the national landscape is set into the framework of a discourse (discursive landscape).

The poem I love sweet Armenia’s…, of course, is the quintessential example of this: a symbolic landscape transposed onto the national discourse. It qualifies: sun-baked, lilting, mournful, steel forged etc., sets aside and distinguishes: “For my homesick heart there is no other balm / No brow, no mind like Narek’s, Kouchak’s”, it affirms historic continuity: ancient, thousand-year-old, and mount Ararat alludes to Biblical lineage, ultimately constructing and consecrating a space for the national identity.

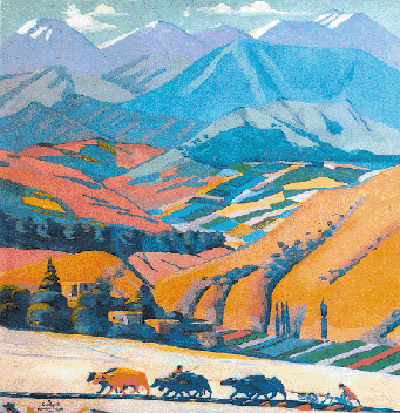

In this respect Saryan’s painting Armenia (1923) is pretty close to Charents’ poem. The difference is in what permeates all of Saryan’s canvasses of the period – the pathos of transformation: the land in the interminable progress of being. Dancing girls are part of the landscape both in with Charents and Saryan (“Blood-red flowering roses in the accents, / The lilt of Nayirian steps still danced by girls”). In the painting they dance on a rooftop, which anchors them to the home, women’s space traditionally. In the poem, on the other hand, halos over Narekatsi’s and Kouchak’s brows are symbols of cherished cultural identity, and in another painting from the Armenia series, Mountains: Armenia (1923), ploughing men rule the nature, till and improve the land.

Hence a woman’s naked body required mechanisms for artistic comprehension that would ensure a diversity of a socially developed bodily forms and a possibility for the emancipation of the body, a movement towards an autonomy understood in a certain sense, in Clark’s words, transformation. Whereas the logic of the “emergency situation” of national self-determination works in the opposite direction: returning the woman to nature, identifying her with the native land and the inner space of the home, where a woman is defined by her most primeval progenitive, nurturing and protective properties.

Let us recall that the first half of the 1920s was a period of heated cultural debates and struggle, and Saryan and Charents were in opposing camps, at least by their convictions. Between I love sweet Armenia’s… (1921) and Armenia (1923) there emerged Armenian Futurism (The Declaration of the Three, 1922, by Charents, Vshtouni and Abov). So let us go on with this imaginary dialogue between the poet and the painter: in 1923 Saryan also painted the portrait of Yeghishe Charents with a very characteristic oriental mask in it, which, I believe, may be interpreted as a response to the Declaration. And although the most prominent feature of “Armenia Reborn” in those years was the so-called socialist construction, we see a purely rural landscape in the painting Mountains: Armenia (1923), with farmers and a plough. The magazines Ascent (published by the Association of art workers of Armenia, chaired by Alexandre Tamanian, with Martiros Saryan as his deputy) and Standard (Yeghishe Charents, Karo Halabian, Michael Mazmanian) carried on with this debate. While the Standard was a proponent of militant art, the constructivist method and, ultimately, the class and ideology interests of the proletariat (maintaining, among other things, that fine arts were facing extinction), the Ascent was discussing the issue, in conditions of a new culture, of developing a new “national style” based on local tradition (the article by Gabriel Gurjian).

Here is how Carl Schorske, an American historian, describes the approach of Eastern European Westernizers (Bela Bartok, Georg Lukacs et al): to adopt any model of modernization, embrace modernism from, say, Vienna, and at the same time to oppose Vienna, leaning on the popular tradition, the ethnic legacy. To strive at the same time to be both modern and ethnic. I believe that the efforts by Saryan and others in this period were also marked by this dichotomy, but it is also obvious that the aspirations of developing a modern “national style” invariably contain elements of cultural resistance.

Of course the Soviet avant-garde was marked by extreme gullibility in putting Western technologies to the service of building a socialist society, constructing a new man. And only in the 1960s, when there appeared serious stimuli to consider the possibilities offered by other technologies, it seemed quite appropriate to pose a question “was a socialist (non-capitalist) technology at all possible?” And artists intent upon the “national style” should have been interested in the issue of orientalism. The last part of this article is devoted to a tentative and very brief discussion of the former.

The question of Orientalism

The quest for the “national style” has gained in urgency, among other factors, from the desire to oppose the universalism of the avant-garde. As opposed to literature, the Armenian painting had inherited almost nothing from the pre-Soviet era (Yervand Kochar reflected on this in 1926 in an article devoted to Saryan). Instead there was the Western (and Russian) tradition of representing the Orient, and the influence of Orientalism was unavoidable for artists who had undergone the formative influence of the Russian school of painting. Although Orientalism in painting originated in Europe, at the beginning of the 20th century Russia, which had embarked on a course of Westernization, had accumulated a rich tradition of representing its “own Orient” and the Caucasus in particular. Saryan’s attempt at overcoming Orientalism was a remarkable feat of cultural resistance. Maximillian Voloshin, Kostan Zarian, Yervand Kochar and, later, Saryan himself refer to Orientalism in the context of his paintings. Later on the subject got obscured; in the Soviet Armenian cultural mindset of the 1960s the Orient hardly existed as an issue.

Under the influence of Edward Said’s Orientalism the development and dissemination of postcolonial studies could have revived the interest towards Russo-Soviet Orientalism in post-Soviet societies. One of the attempts to apply Said’s approach to painting was Linda Nochlin’s essay The Imaginary Orient, 1989. A distinction is made between Orientalists per se, like, for example, Jean-Leon Geromes and its affiliates like Eugene Delacroix. Here are some of the essay’s findings: the first thing that meets the eye in the works of the Orientalists is the absence of history; the rites and customs are beyond time. The Orient they portray is static, time has stopped there. No Western people are ever to be found in those paintings, but the West is always tacitly present in them: the Western colonial or touristic presence, the controlling gaze, the gaze which brings the Orient world into being, the gaze for which it is ultimately intended. The next obvious feature is the abundance of idle people, the almost complete absence of scenes of work or industry, reaffirming the percept of the lazy Oriental man. Two fundamental ideological assumptions about power come to the forefront in Orientalist painting: one about men’s power over women; the other about white men’s superiority to, hence justifiable control over, inferior, darker races.

In his article (1913) on Saryan’s art Voloshin tries to demonstrate that Saryan was not an Orientalist in a manner that of itself possesses salient Orientalist features: as though there exists an unified East, of which Saryan is the scion, and the essence of which is cognoscible and reproducible through the medium of painting. We encounter the same in Andrey Beliy’s Armenian notes (1928): Saryan synthesizes-elevates local landscapes to the level of schematic images, portraying “the Orient in general.” Moreover, for him Armenia and the Orient are identical, although in Saryan’s 1923 paintings Armenia seems to have already been clearly delineated-distanced from the Orient…

Anyway, these issues will surely benefit from a detailed analysis. In the meantime Orientalism remains one of the insofar uncharted approaches to thinking about 20th century Eastern Armenian identity, while also relevant to the study of the current situation, where the signs of Armenia’s re-Orientalisation are apparent.

Translated by Artashes Emin

Photos

a/ Armenia, 1923; d/ Date-palm,1911.

b/ Mountains. Armenia,1923;

c/ Portrait of the Poet Yegishe Charents,1923

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment