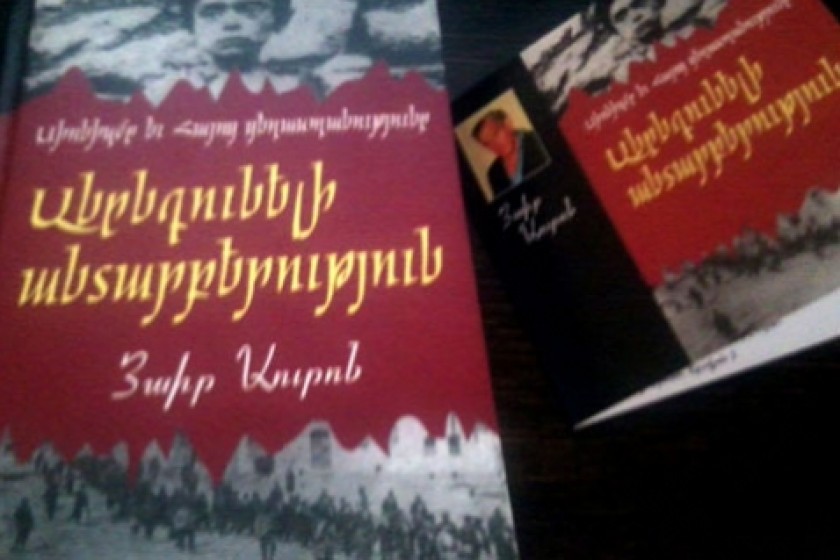

Yair Auron: The Holocaust and the Great Calamity

Holocaust – A Difficult Title

In his book, The Banality of Indifference; Zionism and the Armenian Genocide, Israeli historian Yair Auron writes:

“It is hard for me to understand and accept the longstanding policy of my government rejecting the genocide perpetrated by Turkey against Armenians. I had hope of finding greater compassion regarding the sufferings of the Armenian people, given the similarity of our fate, of finding more attempts to help and assist, even given the limited resources that the Jewish people had, especially the Zionist movement and the Jewish community of pre-state Palestine. Instead, I found an unacceptable indifference and an attitude where the individualistic dominated over the universal.”

These are the words used by the courageous Jewish historian to portray his inner crisis to struggle for the truth that for many years has collided with the iron doors of Israeli state indifference. Travelling a long road, the Jewish intellectual has reached an important conclusion, according to which peoples that have been subjected to genocide must be the ones who struggle the most to prevent future genocides and extend a hand of assistance to all those who have, either before or after them walked the bloody road of crucifixion.

The Jewish people have no road of crucifixion – It has replaced the long road of pain with the road of powerful struggle, and it has conquered that road with arduous blood and sweat.

I will never forget the following lines of Armenia’s poet Romik Sardaryan, who, in 2006, wrote: “Israel has a powerful past, but it’s unforgiveable that today it seeks revenge of its history from its neighbors.”

Poet Sardaryan uttered these words at a time when Israel was using its most powerful weapons to rain down fire on all of southern Lebanon, using as a pretext the capture of two Israeli soldiers by Hezbollah. Even before this, the attitude of the writer of these lines towards Israel was negative. (Sadly, my readers in Armenia will not be able to understand the fundamental reasons for this attitude, which resulted in us bearing the traces of the bloody Israeli talons on Lebanese soil)

I write this preface to explain, in a word, just how difficult and complex a subject the Holocaust of the Jews is to write about. This burden becomes even more cumbersome when for a moment one relives the hate towards Israel that has taken root in Arab circles. This hate is the pages torn from a living diary. Its titles are quite clear – Gaza, Lebanese Qana, Palestinian Deir Yassin, Khiam Prison, the painful cries of protest of thousands of Palestinian prisoners, and the march of struggle of the strong Palestinian people merged in the songs of blood and olive trees. For Arabs today, Israel is enemy number one, and the West has no need to hear these voices from hell or to even attempt to understand the basic reasons for this hate. The reasons for such accusations of enmity run deep and I’m certain that this article is not at all inclined to examine these reasons.

The total image given to the Genocide, deep within us, has been turned into a stereotype. At minimum, the pain is transformed, travels to new expanses, changes color, changes form, but remains the same in general. We are the inheritors of pain and, no matter how epic such words might seem, it is true, especially for those whose ancestors were driven from western Armenia. We have carried this pain, this instinctive “white blemish” with us till today. The same is true for the Jews for whom the issue of grief, the Holocaust, has served as the most unifying of factors, allowing them to recognize one another and live together.

It is in that same pain that more than six million Jews were annihilated. The event became one of historic significance and, doubtless, a new starting point for yet another rebirth from torment, death and injury.

Yair Auron Comes to Yerevan

The book launch for the Armenian version of Auron’s book in Yerevan was an historic occasion. The author took the stage and addressed the assembled crowd, conveying his heartfelt words. (I should add that Banality of Indifference was first published thirteen years ago in Hebrew. It was subsequently translated into English and Russian. Anna Safaryan translated it into eastern Armenian. Karen Baghdasaryan, an Armenian businessman in Russia, covered the publication costs.

At the reception, Auron thanked the Armenia press for its coverage of the book, noting that “it would have been nice if reporters in Israel showed the same interest in the book.”

The true importance of the book was described by Dr. Ashot Melkonyan (Director of the State Academy of Sciences’ Institute of History and a corresponding member of the Armenian Academy of Sciences) who uttered the following thoughts in a short conversation I had with him:

“There was a certain kind of expectation in the public and in the field of historiography regarding the words of the Jewish academician since the Jewish people, who experienced a genocide, should have been the first to comprehend, from a political, economic and moral standpoint, what happened to the Armenians in 1915. With this in mind, Yair Auron finally had the courage and used such a bold title for his work, Zionism and the Armenian Genocide. In fact, he substantiated that the phenomenon of the return home of the Jewish people, a two thousand year-old dream, didn’t necessarily assume that it had to take place at the expense of another, including that of the Armenians.”

The wound of Gaza is the same wound as “the lament of Adana”

The genocide theme will remain a priority as long as there is the issue of recognition. Today, that demand is one-sided. While new voices are being heard from the Turkish side and, with the road blazed by Hrant Dink, I am sure that a new space will be created in Bolis and other Turkish towns in this important process of recognition that has begun. Today, the Turks have a need to recognize us, and naturally, if we still aren’t talking about an agreement, we must talk about a conversation. This conversation will begin somewhere.

Perhaps, the importance of this conversation is still not understood by the Diaspora, or almost unacceptable, however, to hold on to that wound in our gut, to live that melancholy of grief alone, I believe is no longer serves as a life raft. The grief of the Genocide has even grown tired of us. It would have been absurd to hear all this from Auron, a person who sees and condemns the Genocide perpetrated against Armenians, had he reservedly and silently passed over the Palestinian issue.

In this respect, I believe it is important to cite the following passage from his preface relating to the Palestinian issue, a tangled web that causes him such anxiety.

The future of the Israeli state is greatly dependent on a resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, on the elimination of control regarding the Palestinians. This is an unacceptable realty in human and moral terms, as well as from a Jewish perspective and especially from a Holocaust legacy perspective. However, the majority of Israeli youth respond not to the call of Yehuda Elkana that “this must never happen again”, but repeat the Zionist lesson of the Holocaust that “This must never happen again to us”.

Only by following such a set of standards can a true path to the future be opened. Auron steers clear of setting double standards and in this he can serve as an example for others.

Turkish society has much to cull from Auron in this regard. While it condemns the plight of Palestinians in Gaza it wishes to pour cold water on the genocide perpetrated by the Ottoman Empire. Such an approach is nothing more than empty verbal gymnastics and denial.

But this thick wall of silence will crack somewhere. Auron writes about genocide to sound the alarm or to prevent such a calamity from occurring in the future. In this respect, he points out that it’s unacceptable to remain silent about the tragedy that has happened and, going further, he believes that remaining silent and inactive can be regarded as complicity.

In conclusion, I want to broach the following thought contained in Auron’s book that speaks about the murder of an entire world when just one person is murdered. If the murder of just one individuals is so profound and tragic (equal to the pain of murdering an entire world), then what will the Turks, who have carried the burden of multiple genocides in their souls, think about this – about a pain that must cease to be a stereotype?

And I write all this not with enmity because, in the end, the traces of blood are not on my hands, on Yair Auron’s hands, or the hands of others.

Those with the traces of blood on their hands know all this.

But it is important to lend an ear, to listen.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment