Armenians in the Service of the Ottoman State Apparatus

Armenians, forcibly converted to Islam, become grand viziers and statesman

All official posts in the Ottoman government were filled by Osman Turks, other Muslim peoples and Islamized Christians, since the right to govern was the monopoly of the Muslims. The Islamic Shariat, the code of law derived from the Koran and from the teachings and example of Mohammed, did not allow for a Muslim to be subjected to the will of a Christian.

Thus, for many centuries Armenians were far removed from positions of power in the Ottoman government until the 1839 Tanzimat reforms. That is unless, of course, we do not count those few notable Armenians who, seized from their families at an early age during the child conscriptions or devşirme (the practice by which the Ottoman Empire conscripted boys from Christian families, who were taken from their families by force, converted to Islam, trained and enrolled in one of the four royal institutions: the Palace, the Scribes, the Religious and the Military).

The conscription of Christian boys

The cavalry was commonly known as the “Kapıkulu Süvari” (The Cavalry of the Servants of the Porte) and the infantry was the popular “Yeni Çeri” (translated in English to Janissary, meaning “the New Corps”).

The “devşirme” were collected once in every four or five years from rural provinces in Balkans, and only from non-Muslims. It was Murad I, the first Ottoman sultan, who devised the ‘boy collection’ in the second half of the 1300’s. It lasted until the mid 17th century. The Janissary Corps itself was officially abolished by Sultan Mahmud II in 1826.

Thus, for 300 years, the best and brightest boys of the Armenian people were culled, forced to convert to Islam and wound up serving the interests of a foreign government.

It is not known how large the purely Armenian element was in the Janissary multitudes. There were individuals in the Janissary Corps of Armenian origin that were able to attain positions of high rank in the Ottoman military and government due to their bravery and skills.

Armenian commanders and grand viziers

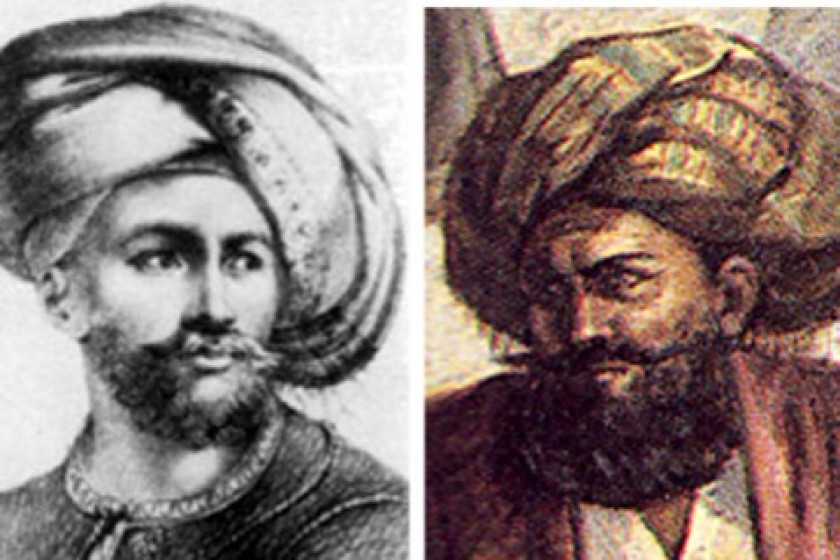

A notable Janissary of Armenian origin was the 17th century naval commander and Grand Vizier Khalil Pasha, whose acts of courage have been glorified in the annals of Ottoman history. He was appointed Grand Vizier after emerging victorious in a 1609 naval battle. He thwarted the Kazak forays from Sinope and renewed the peace treaty with Poland and Austria. He fought against the Persians in 1619 and forced Shah Abbas into signing a ceasefire treaty.

Of Armenian origin was the Ottoman commander and political statesman Ermeni Suleyman Pasha (1605-1680). Due to his God-given talents, cleverness and valour, he was able to rise from the ranks of a common soldier and become Grand Vizier and one of the most renowned figures in Ottoman history. Suleyman Pasha wasn’t the first Armenian forcibly converted to neither Islam nor the last. However, he was perhaps the only one who never hid his national roots and he always used the term Ermeni (Armenian) in his official rank, even while Grand Vizier.

The 17th century Ottoman politician Khousrev (Khosrov), an Armenian who came up through the Devshirme process, also reached the lofty rank of Grand Vizier.

The Ottoman rulers not only used their Christian subjects to strengthen the ranks of the military but also for the Ottoman court. Many of the best looking and brightest boys from the devshirme were sent to the court of the Sultan. The term “Ich Oghlan” refers to the boy servants thus recruited and who worked in the Andarun, that is, Inner Palace, one of the three parts of Topkapı Palace. In other words, they were the Inner Palace servants, or in the language of today, the staff serving in the head of state’s residence. The same term was used for certain members of the Janissaries.

The “Ich Oghlan” runs Ottoman state apparatus

The term “Ich Oghlan” refers to the boy servants who had been recruited according to the Dawsihmah System, and who worked in the “Andarun”, that is, Inner Palace, one of the three parts of Topkapı Palace. In other words, they were the Inner Palace servants, or in the language of today, the staff serving in the head of state’s residence. The same term was used for certain members of the Janissaries. This caste, if you will, played a prominent role in the strengthening and development of the Ottoman state bureaucracy or machinery.

One of the Armenians who rose to high Ottoman administrative office was Kara Mehmed Pasha Doghanju, the elder brother of naval commander Khalil Pasha. He became a state minister and was beheaded at the end of the 17th century due to a rivalry with the Bosnian Grand Vizier, Ibrahim.

During the 18th century, the Ottoman Empire experienced a brief period of reform and development where the government tried to emulate the experiences of Europe. The Ottomans made the foray into printing, libraries were established, magnificent public and state buildings were constructed in Constantinople and towns and citizens throughout the empire saw improvements as well.

Armenian “Pashas” known and obscure

The driving force behind this process of reform and rehabilitation was Nevşehirli Damat İbrahim Pasha, (1662-1730) of Armenian roots. Evidence of the Pasha’s Armenian roots is to be found in the Ottoman history written by Alphonse de Lamartine and published in Paris in 1855. The fact that he was Armenian perhaps explains the tolerant attitude he displayed towards Armenian subjects in the empire. It was during his reign as Grand Vizier that the Armenian churches of Sourp Asdvadzadzin in Kum Kapi and Sourp Kevork in Samatya, as well as other churches in Constantinople, were rebuilt. In 1724, Hovhannes Golod, (Patriarch of Constantinople from 1715 to 1741), protested to Grand Vizier Ibrahim Pasha that Armenians prisoners from the Caucasus were being sold off in the slave markets. The Grand Vizier decreed that the practice be stopped. Armenians in Constantinople, during the reign of Grand Vizier Ibrahim Pasha, were able to make significant advancements in certain fields.

It was during the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid I (1771-1788) that Cezayirli Hasan Pasha Ghazi, of Armenian origin, served as Admiral of the Ottoman Navy, and afterwards became Grand Vizier as well. 75% of those sailors manning the cannons on Ottoman ships were either Armenian or Greek. Armenians also served as standard-bearers on Ottoman war ships.

Hasan Pasha Ghazi was from a poor Armenian family in the Holy Cross neighbourhood of the town of Rodosto. His parents were forced to hand over the boy to an Ottoman merchant as a servant. This merchant gave the boy the name of Hasan. After having spent many years in Algiers (Cezayirli meaning from Algiers in Turkish), he eventually entered into military service with the Ottoman fleet and became famous for the many contributions he made to the navy, including his participation in the siege of the island of Malta. He earned the nickname of ghazi (victor). It was at his initiative that the huge armaments supply base for the Ottoman military fleet and other institutions were built. Ship building also flourished under his tenure.

Some ascribe Armenian roots to İzzet Mehmed Pasha, a prominent Ottoman Grand Vizier of the late 18th century. Perhaps it is merely an assumption based on his kind treatment of Armenians. However, one can categorically state that in addition to Khalil, Suleiman and Mehmed Pasha’s, there were countless other Armenians, forcibly converted to Islam, that rose to prominence in the Ottoman government ranks, but have been recognized as Turks. Either their names have not reached us over the years, or else Ottoman historians never noted their Armenian origins at the time, preferring to be selective with such information.

Armenians began to appear in the administrative life of the Ottoman Empire and their role became more active from the time the system underwent change and there was the perceived need for European style reforms. In the 18th century, the Ottoman Empire began to be called the “Sick Man of Europe” and indeed, the state machinery of the Ottoman state stumbled along like a crippled old man. From the mid 19th century onwards, the Sublime Porte, taking a cue from Europe, attempted to modernize its creaking administrative apparatus.

Armenians in demand during ‘reform period’

But the Turks weren’t ready or able to carry out such reforms on their own. When the time came to set up European style ministries, the need was felt for young Armenian professionals, who, on the one hand, had studied in Europe colleges and universities, but, on the other, were intimately familiar with Ottoman reality and customs. And these Armenian were multi-lingual to boot.

However, Turkish dignity would not allow for the new ministries to be completely handed over to the discretion of Armenians. Thus, many Armenians served as deputies to Turkish ministers in the commerce and trade, foreign affairs, post and telegraph, finances, public works, mining and forest, educations and other ministries. Essentially, much of the work at the ministries was carried out and managed by these Armenians, given that the ministers themselves were oftentimes acceptable figureheads. Occasionally, when the need arose, Armenians were appointed as ministers. These individuals, serving throughout the Ottoman state apparatus, proved that Armenians were not only skilled artisans and merchants, but capable statesmen and politicians as well

Turkish public activist and journalist Shule Berinchek affirms that more than forty Armenians held important ministerial posts during the Ottoman period; including government advisors, members of the Ottoman parliament, ambassadors, etc.

To be continued

Anahit Astoyan

Madenataran; Junior Researcher

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment